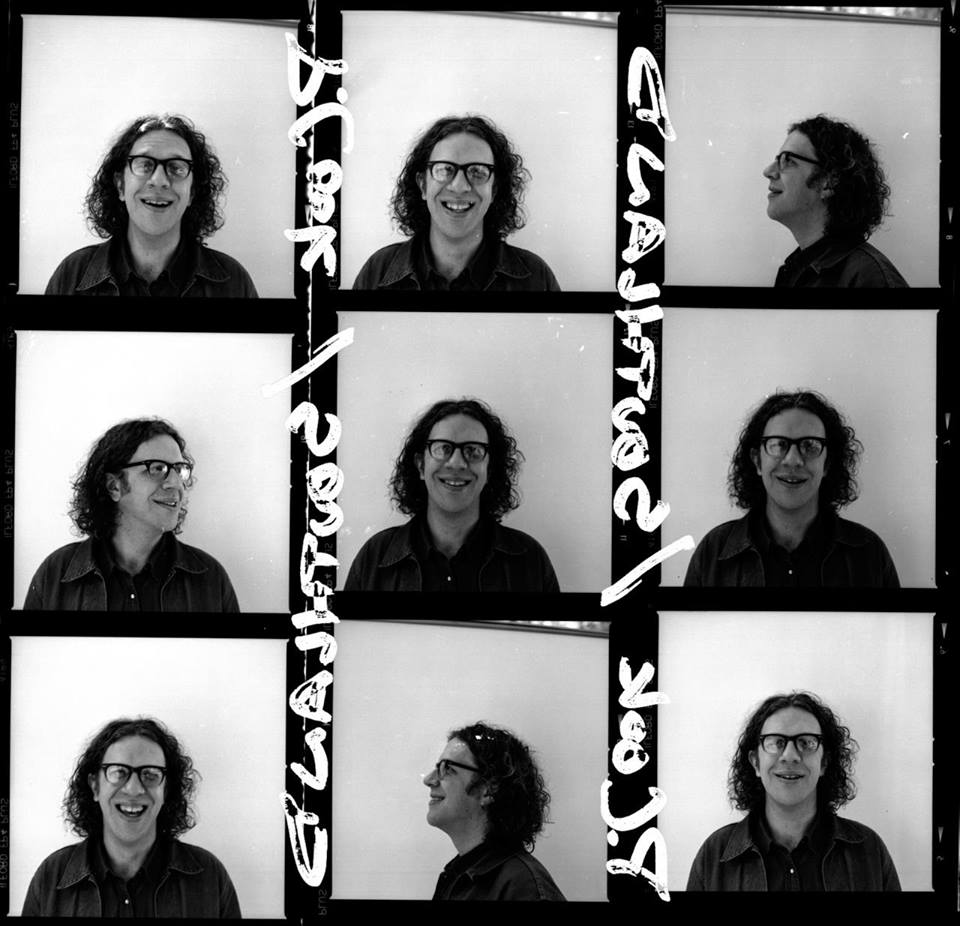

Phil Cook is one of those guys who exudes positive energy. When you speak with him, he’s warm and engaging. As he’s telling you about one of his many projects, he’s overflowing with enthusiasm, sounding like he can barely believe he’s getting to do it. But for a listener, there’s a lot to believe in when it comes to Cook. The 35-year-old Wisconsin native has thrown himself whole-heartedly into working with artists like the Blind Boys of Alabama, the Indigo Girls’ Amy Ray, and Matthew E. White. For the past few months, he’s spent a lot of his time on the road playing keys with Hiss Golden Messenger, who share Cook’s current home of Durham, NC.

In 2005, Cook relocated from Wisconsin to Raleigh, NC, with his younger brother Brad and a handful of other bandmates. One of these, Joe Westerlund, would stick around to help the Cooks form the wild and wonderful Megafaun. Another, Justin Vernon, would return to Wisconsin to make songs that he’d soon release under the name Bon Iver. In 2007, Cook and his partner, Heather, bought a house in the adjacent city of Durham, where they still live with their four-year-old son. As Megafaun fizzled out, Cook wrote and recorded simple guitar and banjo material as Phil Cook and His Feat, which allowed him to begin developing his voice as a solo artist. His forthcoming record, Southland Mission, is more than just another solo album — it blows just about everything that Cook has ever done out of the water. From his front porch, Cook talks about the long gestation of Southland Mission, which covers ground from soul, gospel, and Americana all the way to good ol’ rock ‘n’ roll. It’s a bright celebration of music that Cook says is the best thing he’s ever done.

You’re really big into American roots music. How did that fascination begin for you?

I was one of those kids who grew up, and my parents were both hippies. My parents were both involved in protests; my parents were both involved in all kinds of stuff in Madison, WI, which was a big counter-culture epicenter. My dad had a huge record collection, and he had, like, a thousand records when I was growing up. One of the things that happened, growing up, one of the ways he curated his record collection for my brother and me was — one of the things you do up north is you go downhill skiing. My dad was on the ski patrol. So my brother and I went skiing every week, and we’d go on these winter break trips over Christmas, and we’d go for 10 days way up north. My dad would take off the day before we left. He would take off of work and his whole purpose for that whole day of taking off was he would make a vinyl-to-cassette mix tape for the whole day.

There was some overlap every year, but he made this ski tape, and we would drive up in our minivan — Brad, dad, and me — and it was the only thing we listened to the whole way up … a four-, five-hour drive. And then my dad would take it out — he had a Walkman — he would put headphones on, and my dad would ski to his tape all day long. My dad is the best skier I’ve ever seen in my entire life. He looks like a swan up there. So it’s all this stuff about seeing my dad in his natural element, with listening to all this really great music. My dad had a ton of Muscle Shoals stuff on there, a ton of Memphis stuff on there. Every year. The one song I remember being on every single mixtape was “Try a Little Tenderness” by Otis Redding.

That, I think, was the beginning. That was me when I was like seven or eight. The joy of the music was infused with the joy of what my family did together, how we bonded. Watching my dad in his most natural element, seeing my dad in his purest form. All soundtracked by this music. The older I get, the more I realize those ski tapes are the foundation of my entire musical understanding.

Do you still have any of those tapes?

I would love to find out if there are any of those tapes around. Probably one of my dad’s most favorite artists of all time are the Neville Brothers from New Orleans. So there would always be New Orleans music. The Neville Brothers would be on there. That’s how it started. Really and honestly. I’m from the north, and the closest big city is Chicago, so it makes sense that my dad had some records that were Chicago records, because they would come through the college areas when my dad was going to school. So there’s a white blues band called the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, which came out in the late ‘60s, and they were all white Chicago kids who were obsessed with blues and would just haunt the South Side Chicago clubs. They learned from Muddy Waters, and they learned from all the people like Little Walter and Otis Spin. That’s the first stuff I latched onto.

For a kid growing up in a great northern Midwestern city … there are no black people, and I didn’t see black people until I was, like, 14. So the music that I listened to had an otherness to it that was so far removed from my daily routine. It just existed in my mind in this far-off place, kind of. So there’s a natural part of being a kid and who I was thrown by, or whatever. A lot of the first artists that I really latched on to in any genre ended up just being these relay artists.

I found the further I went back, the more I would just love the purity of some stuff that would happen. Paul Butterfield Blues Band, a white blues band from Chicago in the ’60s, I started there, but it was such a direct connection to Muddy Waters, that was the next obvious thing to go to. That’s what I love. I love seeing where it all grew from, and I think that’s what it is. The more time passes, the more history we have. Linear time is gone in 2015. You can try and stay on the hood ornament of the freight train and try and stay up there, or you can find what inspires you. That’s what inspires me. That’s it. That’s what makes me happy at the end of the day. The water and the cells of my body vibrate to gospel music. I don’t know why. They just do. So I gave that to my body. It’s good.

When you play with other peoples’ bands, you tend to do more keys, but your solo stuff has been more string instruments like guitar and banjo. Why is that?

I grew up playing piano. I started taking lessons when I was four, but I started playing when I was three. I would just sit at the piano. It’s the instrument I don’t have to look at. I just close my eyes and play. Even though I haven’t “practiced” piano in 10 years, it’s still my most expressive instrument. So when I play with Mike [Taylor, Hiss Golden Messenger], or some of my old friends like Justin, they know me as a piano player. They look at me and they see a piano player and they love whatever I do.

The string stuff happened after I moved to North Carolina. That’s when I started learning guitar. It’s when I started doing all the other stuff. It just became the thing that I passed the time doing, just sitting on a front porch, because it’s so fun to sit on a front porch and play. That grew very organically, just out of being here, writing songs, doing little ditties that were just fun and little. They both have different ways of speaking — the instruments do. Different languages that you can use, but you can also share. My favorite thing to do is to play something on the piano, a very pianistic thing, and transfer it to the guitar and see how it sounds. That’s why the fingerpicking makes sense, because it’s piano-like to me. Conversely, you write something on the guitar and transfer it to the piano — that’s my favorite thing to do … cross my languages. I geek out about that stuff. It’s fun for me.

How long have you been working on Southland Mission?

Two years. In between Megafaun tours, I came home and started making these little solo records. Once I had a handful of songs, I would just come home and record it in one day. I never had to look at it. It just gave me an out to forgive myself for the mistakes I would make all over it. It was also just simple. Everything was simple about it. That got me onstage and in front of people.

I guess I just realized, at some point, it was just a matter of meeting certain people. They kind of unlocked certain doors that sent me reeling on a journey. A journey of fate that has been, probably, building since I was 14 and met Bruce Hornsby. When I think about the record, it’s been that long in its incubation. The Blind Boys record I did, that was the first unlocking. That was like the baptism. That was the unveiling. I was like, “Oh, I can do this. I can pursue the music that I’ve always loved and incorporate it into something. I can hang.” It was such a pleasant surprise to find out that I just want to make good music, and so do they. It was really easy to find common ground. My brain just fired after that. I started coming up with all these ideas and sitting down, and all these songs and ideas that weren’t Phil Cook and His Feat, it wasn’t these front porch ideas. It was this really big sound I heard in my head.

That’s how I view Southland Mission. I just had to go do this thing. It had to come out of me. I didn’t realize it had to come out of me, but it had to. It took me away from my family, and took me away from being present in any conversation for the last two years. I was gone. My mind was just completely on it. But it was a really spiritual journey, and these are the teachers I met along the way that sent me to the next thing. I love it. I’ve never been so proud of anything in my entire life. It’s the thing.

Photo credit: DL Anderson Photography