Richard Thompson’s new album contains 13 tracks and is called 13 Rivers, which suggests an intriguing metaphor regarding music and bodies of water. These are songs as rushing currents, as tributaries cutting through the landscape with unstoppable force; they can be dammed but not contained, their power harnessed but not diminished. Or perhaps they are obstacles to be crossed, either by swimming against dangerous rapids or by devising elaborate feats of engineering. It is any wonder that songs have bridges?

Thompson admits he didn’t think too hard about it. “It’s just a convenient title, and I liked the way it sounds,” he says with a chuckle that sounds both self-deprecating and possibly curious about the idea. “I’m not sure how deep it is or if it stands up to intellectual scrutiny. I guess songs and rivers can be fast or slow, straight or meandering. They have a beginning or end. You should make of it as much as you can. The more you make of it, the better I sound.”

He doesn’t need me or anyone else to make him look smart, but let’s go ahead and make too much out of that metaphor. Thompson’s catalog is full of raging rivers, most with rock rapids and treacherous oxbows, some stretching for miles and miles or years and years. He’s been navigating them for more than half a century, ever since he strummed his first notes as the guitarist and occasional songwriter for the famed London outfit Fairport Convention. That band helped to electrify folk music in the late 1960s, adding drums and Stratocaster to centuries-old rural ballads about maidens and knights, before Thompson went solo to emphasize his own songwriting.

For years he was merely a cult artist in the States, his early records available only as imports, at least until 1980’s Shoot Out the Lights—written, performed, and recorded with his then-wife Linda Thompson—established him as an insightful chronicler of the challenges of commitment and contentment, a songwriter who is neither blandly optimistic nor cynically dismissive, but somewhere right between bitter and sweet.

And, of course, he is a guitar player whose resourcefulness somehow dwarfs his technical virtuosity. A teenager in the late 1960s, he was too young to be as enamored with American blues as other players were, which means he was never a contemporary of Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, or Jimi Hendrix. Instead his playing is grounded in folk music, aligned with the experiments and excursions of Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, and Davy Graham. Like them, he has significant range, incorporating a range of styles and sounds: African desert rock, urban punk, country & western, Indian ragas. His solos change shape constantly; listening to him play, you never know where he’s going but you know he’s going to get there.

While many of the players listed above have either died or all but retired, Thompson continues to make relevant music in the 2010s, both as a songwriter and as an instrumentalist. “The most important thing is the song—the particular batch of songs you find yourself with. That dictates so much about the way the record sounds,” he says. “The songs are going to tell you how they want to be shaped, how they want to sound in the end. They tell you if they want to be acoustic or electric; they tell you if they want to be simple or complex. If you’re listening to what the songs are saying to you, then making the record should be a fairly easy task.”

The batch of songs that comprises 13 Rivers stemmed from what he calls a “difficult time in my life,” although he declines to discuss the specifics of those difficulties. Still, it’s possible to gauge the general nature of them based on songs like “Rattle Within” and “Shaking the Gates,” which suggest a feisty relationship with the idea of mortality. Writing them, however, is not necessarily a conscious effort to address certain events or predicaments. “It’s a semi-conscious process. You’re not always thinking about the big picture. You’re just kind of floating sometimes. You’re almost allowing yourself to switch off some of your critical faculties in order to write. And once you’ve written it, you think, okay, here’s this song, now what does it mean? But you’re not thinking about that meaning while you’re writing it.”

Take the opening track, “The Storm Won’t Come.” A low, brooding number with a worried vocal and a searing solo, it reverses the typical storm metaphor, casting the thunder and rain as something other than destructive. Especially opening the album, it almost sounds like an invocation by an artist waiting for inspiration to strike like lightning. “That’s not what I had in mind, but that sounds great! I was thinking more than sometimes in life, you can feel stymied and you long for change. Sometimes if you try to change it yourself, it doesn’t work. You have to wait for the world to do it to you,” he says.

One storm arrived just after he had assembled this batch of songs: The producer backed out of the project, leaving Thompson to ponder its fate. Thankfully, pragmatism won out. “I thought, well, the studio is booked, the musicians are booked, we’ve got the material, so I’ll just produce it myself. I’ve done it before. It’s always nice to have the contrast of working with other people, but it can be good to do it yourself. You can get more into the nuts and bolts of what you really intended to find in the songs.”

Perhaps that’s why so many songs have a raw-nerve friction to them, lyrically and musically. After a handful of solo acoustic albums, including 2014’s Still, produced by Jeff Tweedy, Thompson put together a very tight, very agile rock and roll combo to give these songs a jittery energy. He’s worked with bassist Taras Prodaniuk and drummer Michael Jerome for years, “so I know them a bit—what they’re likely to come up with.” They worked quickly in the studio, learning the songs just enough to pound them out but not enough to pound them life out of them. “I try to not get too embedded in learning the song. We just give it a couple of listens at rehearsals,” he says. It’s a way to avoid what Thompson calls “overlearning” the song, to allow room for happy accidents and to keep the possibilities wide open.

When the song goes out into the world, those possibilities shrink dramatically. The song becomes settled, more or less. “What the song is now is public domain. It becomes a kind of public property, and the audience won’t let you change it, even if you want to. I’ve got songs where I’ve snuck in the odd word change, but to change a verse or even a line is just asking for trouble.”

Being the song’s creator doesn’t mean he determines that meaning for anyone else. In fact, his interpretation is only one of so many. “It’s always amazing to hear other people’s ideas of what a song is about. I may have written it as a satirical song or a very pointed song, and people will say, ‘Oh that’s about Bob Dylan’ or something. How did they reach these bizarre conclusions? But I’m glad they can find their own meaning in it.”

Illustration by: Zachary Johnson

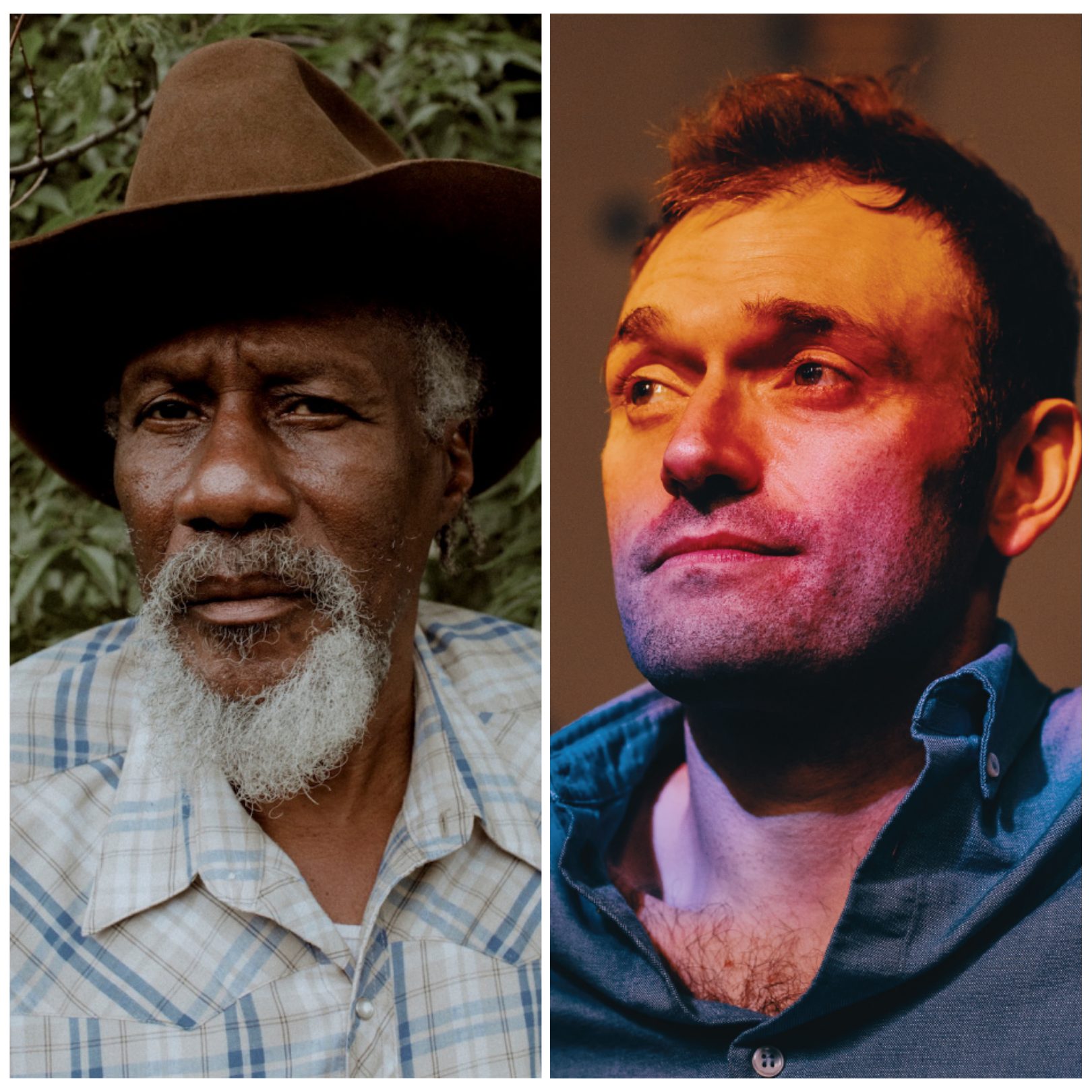

Photo by: Tom Bejgrowicz