To hear Mipso perform, it’s hard to believe that Libby Rodenbough, Joseph Terell, Jacob Sharp, and Wood Robinson didn’t originally get together with the intention of digging into bluegrass history or starting a band. But as the self-described “indie kids” played around with vocal harmonies and playful strings as students at UNC Chapel Hill, the traditional sounds of their native North Carolina beckoned.

“I had a need for exploring my own roots — the places I’m from and the traditions that come from North Carolina and the Piedmont specifically,” Terrell, who plays the guitar, tells BGS. “There’s a lot of depth to the music that’s been made around here, and because a lot of those folks are still making music around here, it’s still passed down in neighborhoods, at jam sessions and orally.”

As Mipso’s audience grew, its sound evolved, integrating elements of pop with traditional strings and vocal harmonies, and the foursome reckoned with more than just chords and lyrics.

“I was trying to make sense of North Carolina and being a more long-term North Carolinian — not just by birth, but by choice,” says fiddle player Rodenbough, of the early days. “There was so much context and story behind this traditional music. Every song, even if it was a modern creation, had little threads that tied it back to words that had been sung for decades or hundreds of years. It just felt like… well, in a nice way, a bottomless pit. Or, what’s a nice way to say that?”

“A well! An inexhaustible well,” offers Terrell with a laugh. And they’re still drinking from it: Last month, the group issued their fifth full-length album, a self-titled effort that embraced the band’s quirks and their past experiences.

“We’ve been living together so closely for the last eight years, and for better or for worse, we’re us now,” says Terrell. “We had phases of the band where we thought, ‘Oh, we’re supposed to be this, we need to make a song this way.’ This record, it was like, ‘Fuck it, this is how we make music.’ We like it, and we’re weird if we’re weird, and if we’re not, we’re not, but this is how we go about it. Here’s Mipso.”

Joseph Terrell: The lyrics and the melodies are certainly an important part of what makes a song, but I think when we talk about combining our voices, we’re talking about making a presentation of a song that makes an emotional impact when people hear it. “Let a Little Light In” is a great example of a song that really transformed in the studio. The lyrics mostly came from me, but Libby and Jacob and Wood had more to do than I did with building this cool, playful soundscape of dancey noises to make up a kind of funhouse mirror of childhood weirdness.

Libby Rodenbough: A lot of the songs are lyrically one person’s, or maybe two people’s, work. But we talk about the meaning of songs when we talk about the arrangements because the delivery of it has so much to do with the emotional meaning. There’ve been songs before that we’ve vetoed or decided to leave off a record because they felt too specific to one person — the rest of the band was going to feel like a backing band. Part of our standard for what makes a Mipso song is that we all have to find an in-road somewhere, something we can sink our teeth into.

You see a lot of bands packing up and moving to places like Nashville or LA, but you’ve held tight to the community where you came up in North Carolina. What makes it such a special place for you, as people and as musicians?

Terrell: For me, North Carolina is where the music comes from, and Nashville or Los Angeles is where the business comes from. In as many ways as possible, trying to keep and hearth and home on the music side of that equation is going to be really healthier in the long run.

Rodenbough: I would say, too, that there’s a part of it that’s arbitrary: Because I was born here and went to school here, and because I believe that there are benefits that you can only reap after a certain amount of time spent in one place, this is the place where I still am. It could have been somewhere else. But it’s North Carolina, because I’m a North Carolinian. This is it.

Terrell: There’s a part of you, a Libby-ness, that’s because you’re from this place. It gets a little bit vague and spiritual on some level to justify it, but I do feel that that’s true somehow.

Rodenbough: We formed the type of connection to a place that we have here by having been born here and having come of age here — by having returned here from every tour for seven or eight years. I have a more intergenerational community of people in my life. I’ve known people when they’ve had babies, and I know their kids now. I’ve met their parents and grandparents. You just can’t really rush that process.

Terrell: I had dinner on the porch with my grandparents three weeks ago — they’re 92 and 94 — and my grandma gave me a CD of my great-grandmother telling stories. It was recorded in 1985. So I’ve just been driving around in my car listening to this CD, and it’s about all these places that I still go. I feel a spiritual connection here that I can’t exactly explain. Yet I would hate to think that this answer could be spun in a way that means, “If you weren’t born in a place, you’re not valuable to that place,” because certainly the reason I love Durham is because of the immigrant community. There’s lots of ways of being from a place.

View this post on Instagram

One song that feels especially prescient on the new album is “Shelter.” I think a lot of people can relate to the idea of seeking out a place to be safe and accepted. What do those lyrics mean to you?

Terrell: That song came from Wood, primarily. He had this great melody that reminded us of a British Isles folk melody. Some of his family in Robeson County in Eastern North Carolina had been really impacted by one of the bad hurricanes, and he had the idea of telling that as a snippet of a story. But instead of making this about one very specific scenario where you’d need shelter, you have four different scenes that land on the same phrase or message — kind of in the tradition of country songwriting. Whether you’re a kid, an immigrant, a person facing natural disasters because of global warming, or the richest person in New York City going up into some big tower, this is a human need for shelter. We all need it, and therefore, we should all think of ourselves as tied together.

Rodenbough: And I think that a lot of the strife — to put it really lightly — happening in the country right now comes from an anxiety about lacking shelter, lacking a feeling of safety. That applies to people who are very clearly lacking in physical shelter as well as people who seem to be lacking for nothing. Our country has failed to provide that for people from every walk of life for a long time now, and so I think that’s one of the reasons that it’s unfortunately especially relatable right now. We all feel untethered. We all feel like we don’t really have a home.

Mipso’s sound developed in part thanks to in-person communities at places like festivals and neighborhood jams. Do you feel like there’s a way to emulate that in online communities?

Rodenbough: For so many subcultures, the internet has given people the gift of knowing that others like them exist. It is very empowering, and in some cases, that’s a bad thing — there are a lot of internet subcultures that we wish probably didn’t have that vehicle. But, for better or for worse, it makes something that probably felt very geographically disparate, and therefore disconnected, feel really strong and unified.

One example during COVID has been a Facebook group called Quarantine Happy Hour: They do a concert every night, or even a couple of concerts every night, and I’ve watched more bluegrass and old time music since [joining] than I did probably in the couple of years prior. It’s like a who’s-who, especially of contemporary old-time players, with bluegrass too. Every concert, no matter how well-known the performers are, has a couple of hundred people, and folks are tipping like crazy. And it’s interesting that it took a pandemic to make that happen, because we could have done that all along.

Even before the pandemic, though, Mipso was really harnessing the power of the internet to reach new fans — even listeners who maybe never considered themselves fans of traditional music.

Terrell: I think we’re probably more like a gateway drug into bluegrass than a haven for diehard fans. We have played a good number of bluegrass festivals and traditional-oriented-type venues, but I think we’re on the fringe of what they consider to be part of that world. If people find our music and like it, they might say, “Wait… there’s something in this that’s leading me towards all these other artists.” But there’s certainly not, like, a big tag we’re putting on our foreheads to weed out bluegrass or non-bluegrass fans.

Are there any misconceptions you think people have about bluegrass or traditional music — things they really get wrong?

Terrell: I mean, I have two things. The first is the idea that it’s white music, which I think is a really pernicious and awful myth. So much of this, the only reason we’re doing this is because it came from slaves who were here, and it came from African American music.

Rodenbough: It’s one of the nastiest and almost most ridiculous perversions of the truth, that white supremacists have used this type of music as an example of anglo-cultural achievement.

Terrell: The other [misconception] is that it’s tame or like, “stripped down.” For me, the best way to understand bluegrass specifically is that it was rock ’n’ roll right before rock ’n’ roll. It was high-energy and rip-roaring — the banjo twanged right before the electric guitar. It was the head-banging music of its day. [Laughs]

Rodenbough: This was a wild music — bluegrass in particular was not an old folky hokey thing. The way that we divide up the genres of traditional music comes straight out of marketing. I think it can be useful to understand how one style of music informs another that came later chronologically or something, but it’s not necessary to draw hard lines between old time and bluegrass in order to love stringband music or to love fiddle-centric music. All the borders are so blurry, just like with everything in history and in our overlapping cultures. I think that’s so wonderful, and I wouldn’t want to try to clean it up. That would be missing what’s so special about not even traditional music, but vernacular music — music that non-professionals make in their lives, about their lives.

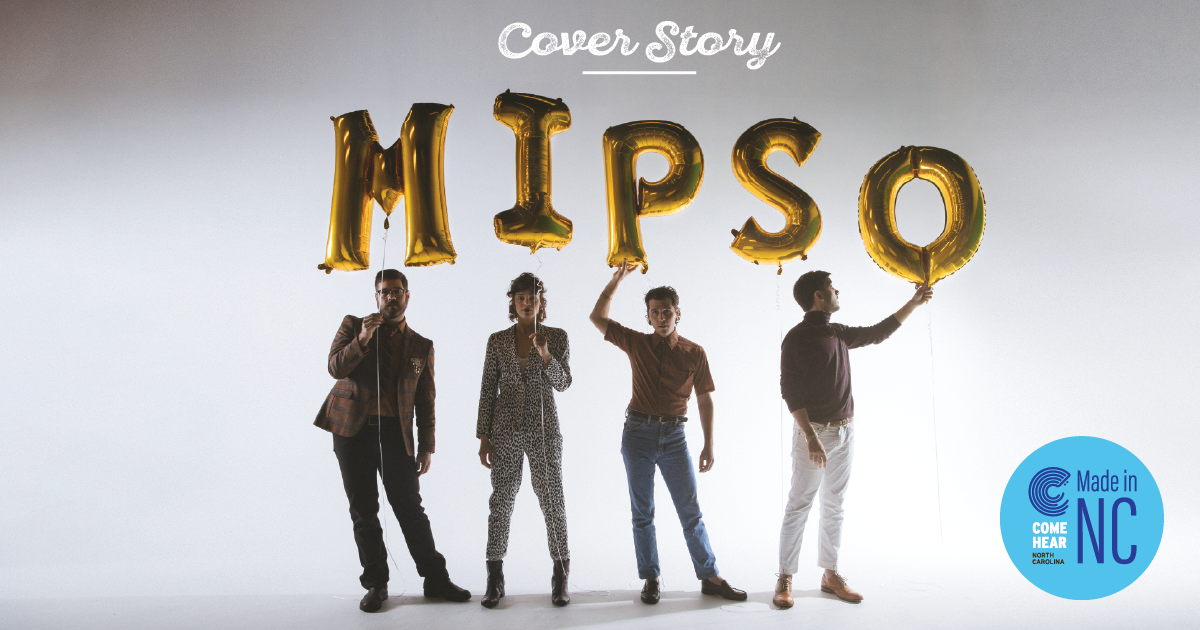

Photo credit: D.L. Anderson