Tim Stafford’s 97-year-old mother, Bernice, still saves newspapers—big stacks of yellowing back issues, should she ever need to retrieve some scrap of local intel. She will clip the occasional notice from those aging pages and dispatch them to her son Tim Stafford, too. The Blue Highway cofounder and former member of Alison Krauss & Union Station now lives 40 miles south of his Kingsport, Tenn., hometown.

Late in 2021, Bernice didn’t even need to cut and post. Instead, she simply handed him a recent series from the Kingsport Times News and pointed at Kinnie Wagner. An Appalachian outlaw, Wagner ran off with the circus, ran moonshine for a sheriff, and repeatedly ran away from jail after killing multiple cops nearly a century earlier. The saga might be a song, Stafford thought, but Bernice just wanted her son to know he was also a dashing folk legend.

“He was this self-styled ladies man. Have you seen pictures of him, that Harry Houdini haircut?” Stafford, 62, says, laughing from his home outside of Greeneville, Tenn. “She wanted to let me know that her grandmother thought he was the stuff. He was a local hero.”

Despite a master’s degree in history from nearby East Tennessee State University and a lifelong enthusiasm for Appalachian lore, Stafford had never heard of Wagner. As he began to ponder the renegade, complexities emerged—his deification by disenchanted locals as a Robin Hood acolyte whose funeral was allegedly attended by 10,000, his vilification by locals who had lost family members to a murderer, the gray area in between. “In the ’20s, before mass media, it was easy to build up this myth,” Stafford says. “But good or bad, it’s the sort of thing that needs to be preserved. His story was definitely a lost voice.”

“The Ballad of Kinnie Wagner” is now an early standout on Lost Voices, an absorbing debut LP written and recorded alongside Nashville songwriter Thomm Jutz. Above darting banjo and pensive fiddle, the pair relay a first-person synopsis of Wagner’s deeds and misadventures, ending on twin notes of resignation and redemption.

That sense of sympathetic storytelling indeed shapes most of Lost Voice’s 14 tales, from a barnstorming Black baseball team in the Appalachian foothills to the region’s amateur physicians and midwives who healed with home remedies passed among generations and neighbors. Lost Voices is a thematically sprawling bluegrass record, reaching across multiple decades, disparate traditions, and far-flung regions to offer cautionary and sometimes complicated accounts alongside songs of hopeful redemption. Think of it as Howard Zinn’s hidden American histories meets Wilma Dykeman’s ethnographic Appalachian books, bound by an unfailingly poised melodies.

“Bluegrass is all about sad stories, morbid stories—murder ballads, you know?” Stafford says. “But one thing I have learned is that there are very few topics that can’t be songs. And some of the ones we have written are pretty far out.”

Jutz may, at first glance, seem like an unlikely writing partner for these songs of the rural South. Born in 1969 in Germany’s southwest corner, not far from the Swiss and French borders amid the Black Forest, he is a classically trained guitarist. But a 1981 television performance by Bobby Bare captivated him, prompting an obdurate interest in country and its kin.

“The allure of this music is that it lives in the past and present at the same time, but it’s almost easier to learn about it if you look to the past,” says Jutz, 53, between classes at Nashville’s Belmont University, where he teaches songwriting. “But I didn’t live in an environment where that was around me, so I had to find it in literature and music. So I’ve always been interested in American history.”

In 2002, Jutz landed a “diversity visa” and emigrated to Nashville a year later, soon pulling triple duty as a producer, touring guitarist, and songwriter. The tunes seemed to pour out. After meeting The SteelDrivers’ Tammy Rogers at a Music City industry soiree in 2016, for instance, their regular writing sessions yielded an astonishing 140 songs before the pair finally released a dozen last year.

He found an even faster rhythm with Stafford, especially after most cowriting sessions reverted to Zoom during pandemic lockdowns. Stafford had played on Jutz’s sharp 2016 solo debut, Volunteer Trail, but their work together first trickled in, with maybe five songs finished during Stafford’s occasional sojourns west to Nashville. During the pandemic, Jutz used the break from touring to earn a graduate degree in Appalachian Studies from Stafford’s alma mater. They’d meet several times a week online and talk about stories they’d recently learned, two regional history buffs swapping new finds. They’ve now finished more than 100 songs together, each an attempt to give volume to one of these so-called lost voices.

“We’d catch up a little bit first: What’s been happening since last week? What have you been reading? Guitars, whatever,” remembered Jutz. “But we had this running list of titles, concepts, and scenes we wanted to write about, all distinctly American. Our cowriting sessions are expensive—we always end up buying books because we talk so much about what we read.”

For his coursework, for instance, Jutz had to dive into The Dollmaker, the lauded 1954 novel by Kentucky writer Harriette Arnow, a tragic work that exposed the unstable underbelly of transitioning from tolerable rural penury to tempting urban prosperity. Stafford had already read it and even gotten to know the family, so discussions of its painful plot flowed. The pair reduced it into four graceful and heartsick minutes, a tender ballad for what’s left behind when you leave tradition in the rearview. On Lost Voices, Dale Ann Bradley delivers the resulting “Callie Lou” with lived-in sympathy, as if she too has shielded her eyes from bright city lights.

Stafford, on the other hand, recommended Where Dead Voices Gather, Nick Tosches’ fraught and freewheeling biography of Emmett Miller, a yodeling star of early 20th-century blackface minstrelsy. His commercial participation in that vile, racist system helped foster country music and all the pop that followed. How would Miller feel, they wonder aloud in “Vaudeville Blues,” to live on infamy and influence? He is neither a sympathetic figure nor abject villain here, just a person weighed down by his choices.

“He informed so many people, from Jimmie Rodgers to Hank Williams,” says Stafford. “But he’s this cat who was so misty that we don’t know much about him. I like that approach.”

Just then, Stafford brings up Jesus, zigging in a way that reflects not only his debut with Jutz but also the ecumenical approach to their partnership at large. As the world’s largest religion, Christianity doesn’t represent a lost voice, per se, but many of its core tenets—“turn the other cheek, do unto others, all very revolutionary stuff,” Stafford says—have been largely discarded in the commodified modern American iteration. The pair harmonizes sweetly during “Revolutionary Love,” more a non-denominational hymn of forgiveness and forbearance than some attempt to proselytize. It feels like a campfire hymn.

Lost Voices’ most disarming quality, though, might be how Stafford and Jutz sing about their subjects with the elan of students and not the stolid erudition of professors, which they have both been. There is a sense of delighted wonder as they deliver “The Blue Grays,” an admiring portrait of a Black baseball team in Elizabethton, Tenn., that proved a formidable foe for two decades. “Code Talker,” their ode to the indigenous Americans whose native languages became an indispensable cryptological tool during World War II, not only celebrates their accomplishments but lampoons their cross-generational oppression in the United States.

This isn’t a political record, Stafford says, but it’s hard not to feel its gentle push for inclusion, empathy, and appreciation, extended far beyond people who happen to look like you. “I know the bias against bluegrass, this music, and the region itself. Some of those stereotypes are based in reality,” offers Stafford. “But there is diversity here, mystery, and these stories are not that hard to find.”

Lost Voices is the public launch of the prolific Stafford-Jutz tandem, not at all the culmination. Jutz has already gone through his Civil War phase; the first song the pair wrote together was actually about it. He is now deeply invested in how the Roaring ’20s gave way to Whimpering ’30s and how those decades continue to shape culture a century later. Decades ago, Stafford gave up his doctoral pursuits (“the application of metaphor theory to the history of ideas,” he says with a bemused chuckle) to instead pursue bluegrass.

But he soon learned about the academic exploration of bluegrass, even getting to know the historian Neil V. Rosenberg. He’s now working on the follow-up to Rosenberg’s canonical Bluegrass: A History, trying to pull that epic forward 50 years. There will be, it seems, no dearth of new interests.

“Everything is interesting, and everything has to be interesting if you’re a writer of any kind—poets, novelists, songwriters, journalists, all first cousins,” Jutz says, his words rushing with excitement. “You look for meaning, living images, things that spark your creativity. That’s the job description.”

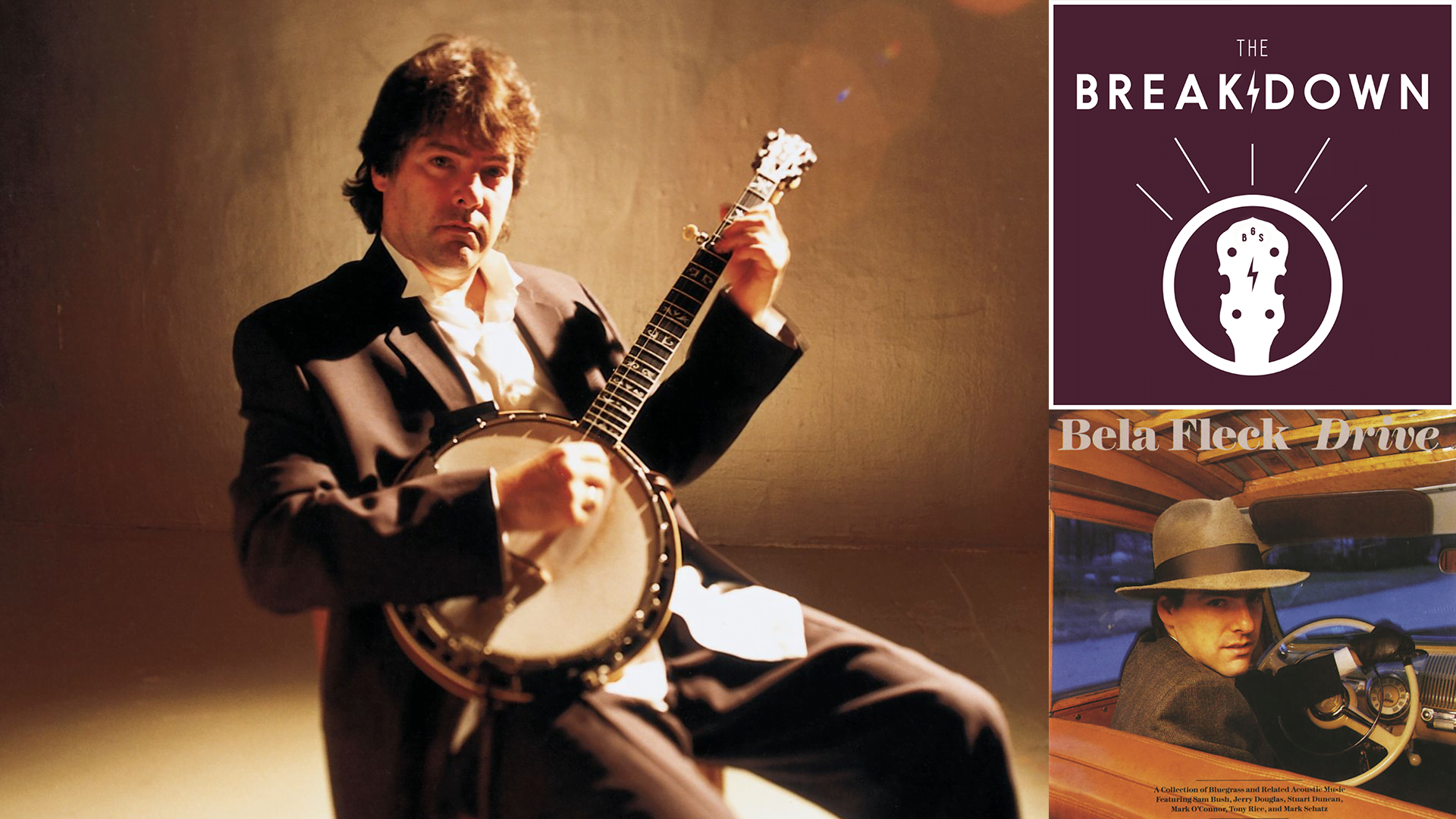

Photo Credit: Jefferson Ross