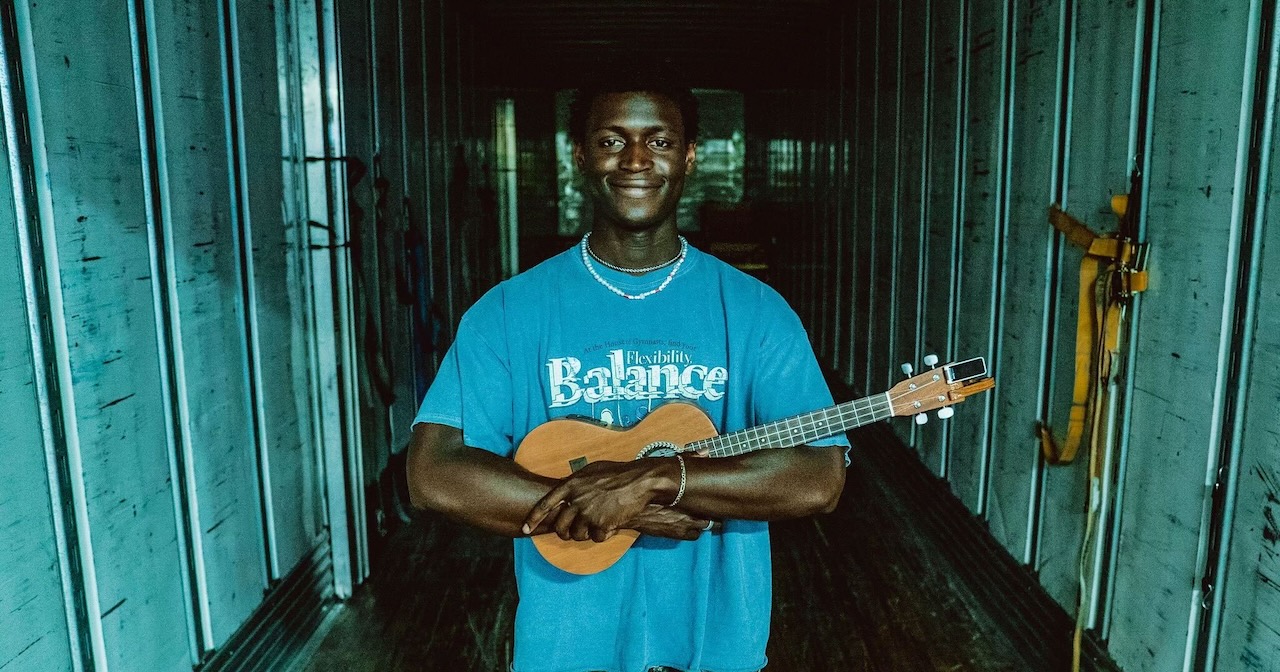

When one really digs below the surface of Mon Rovîa, there’s this intricate kaleidoscope of self, this winding path where the road to the here and now for the singer-songwriter has truly been one of restless resilience, dogged passion, and spiritual curiosity.

The rising artist has already lived this whirlwind existence of trials and tribulations, but also one of triumph and transcendence. Born in the West African country of Liberia, Mon Rovîa (taking his stage name from Liberia’s capital city) was adopted by Christian missionaries and taken from his homeland in the midst of an extremely violent and daunting civil war,

From there, Mon Rovîa bounced around the United States in a highly religious household, one where he wasn’t exposed to modern culture or the endless depths of music, either new or old. But, nonetheless, he fostered many existential questions about his unfolding life, with one main query in the forefront: Who am I?

The intricate nature of Mon Rovîa became heavy and tumultuous within his heart and soul, these deep layers of internal conflict. Being an immigrant in America. Being a Black man raised in a white family. Being adopted with no sense of his biological parents. And being filled with survivor’s guilt about leaving Liberia.

Yet, it was writing in his journals that launched the long process of healing and understanding within Mon Rovîa. Those words, thoughts and emotions soon took shape as songs, all while he began to learn to play the ukulele, guitar and other instruments. Add into that, his continued exploration of recorded music itself.

What has resulted is this unique tone, a vibrant crossroads of indie-folk, Americana, and shoegaze pop stylings, with many viewing Mon Rovîa as a talented rising voice in the Afro-Appalachian folk scene.

Fast-forward to 2025, where Mon Rovîa has become a very popular star on TikTok, yet his soothing sounds and melodies echo far across the massive social media platform. Several studio EPs have been released to wide acclaim, with the latest, Act 4: Atonement, putting a period on this chapter of his art – his eyes now aimed at the unknown horizon of his intent, head held high and optimistic.

When you’re looking out the window these days – in terms of your career, where the music’s going, and also where you’re going – what are you seeing?

Mon Rovîa: From even last year, I think things have accelerated a lot faster than I would’ve hoped in music, to be honest. It still seems really fresh though. It’s a lot of taking in the new fans and a lot of the joy that’s come with the acceptance of the music on a broader scale. At times, I wonder if I was really prepared for all of it, because a lot of these songs and a lot of the roadmap was written from a place of deep sadness and things that I was going through at the time. It’s crazy when you get to the place of living the thing you hoped for and realize that, “Oh man, there’s longevity that needs to be tied along with it now, since it’s becoming something that people are really desiring.” But, I’m very thankful. I try to be truly in tune with my energy and spirit. The world is super heavy and I tend to feel it a lot.

As things get crazier for you, expectations may shift and things change. How do you keep that piece of you that’s honest and real intact in your music?

A lot of it is, for me at least, having perspective. I know that’s easier said than done. But, being able to understand that you’re doing what you love and to be honest with whatever it is you’re presenting. Write what you know, write what you feel.

Your popularity soared through TikTok and now you’re playing more live shows. Has that been an interesting transition in being face to face with your fans that normally see you from behind a screen?

Absolutely. It’s totally different. I’m a pretty quiet, shy person. So now, transitioning to moving from the screen and having that barrier, that river that can divide, all the little things that come into play when you’re face to face? It was a little bit scary at first, especially with the first couple tours we did. With being in front of a crowd, the most important piece I think that I’ve learned now is the stories that I’m telling are the tales of my journey with each song. As I play music, that’s helped me become a lot more confident onstage, because I know what I’m speaking about and I know what the songs are about. It’s not this kind of idleness and just good music to listen to. I try to take the listener a little bit deeper, and that’s fun for me to do that. It creates a lot more fun. I’m just not someone that likes to be in front of a lot of people or be the center of attention, to be honest. I prefer writing things in silence, being in my room and contemplating.

@mon_rovia_boy To those alchemizing your traumas… this is “to watch the world spin without you” 🫂 #folkmusic #mentalhealth #derealization ♬ To Watch The World Spin Without You – Mon Rovîa

With all of this going on, you’re also on this journey of finding yourself and figuring out who you are, where you came from, and where you’re going.

I think every adopted kid eventually hits the point where they want to know so many different things about their life, their story, what their background was. And that’s what was happening to me around the time of [my 2021 album] Dark Continent. And that’s even before we were taking this route of Afro-Appalachia. But, it led me to dive deeper into music and I just happened to be [living in Chattanooga, Tennessee]. Being in this area helped me to dive deeper into where all this music kind of came from and the history [behind folk, bluegrass, and Americana]. So here I am, just a Liberian refugee, but somehow in the perfect hands of history learning from where I was, not necessarily anything else. It is a very full circle moment.

That’s got to be a lot to wrestle with as you get older and you become your own person. I mean, there’s a lot of layers there.

So many layers. But don’t forget, there’s that layer of being the Black kid in a white missionary Christian family. And then the experience of growing up Black in that private school kind of world, having no tie to the African American experience. Being exiled as well from that group, because I didn’t have the same upbringing. I was always looked at as being a white Black person, a Black person that spoke white, because I spoke pretty properly. Kids that have my experience are very lonely, you know? There’s not really a place you fit, because you don’t fit with the white kids because you’re Black in their eyes, clearly. And then the African Americans don’t accept you because you don’t know their world either.

It was a very tough upbringing. I was very quiet and I watched a lot. I learned how to be what I am in social settings, how to relate to [others] and keep things to myself a lot, just try to fit in as best as possible. It was tough. It was lonely. Music didn’t really come to me as Mon Rovîa until 2018, and that’s when I really started to take music a little bit more seriously. [Growing up], it was more of an outlet. It was just a fun thing I did with my brothers. I didn’t think of a career or me being good at it, because nobody said I was good at music or writing music. My friends did like my writing. They thought I was very clever, but I didn’t consider it for myself at that time. I just did it.

With this period of your life and career, it seems Act 4: Atonement seems like the end of the beginning of this chapter of your music and your journey.

Yeah. That’s what Atonement is. It’s the end of the beginning. Everyone is a hero in this story of life. So, everyone has their hero’s journey, whatever that is to them. Some don’t make it to becoming the hero, which is a tragic thing. And some do, but everyone has that journey in their life. For me, this atonement ending is the start of what I am now. I think it gets me to this place where I’ve gone through a lot of difficult things. Hopefully now, in my next chapters of Mon Rovîa, whatever that is, I can atone to the people – people that are hurting and going through different things. The point is, I can hopefully now be some kind of light to these people, where I can tell them things I’ve learned along the way. And hopefully it helps them through their things and through their time. That’s the important piece of what atonement is – the knowledge then turns hopefully to wisdom.

Have you been back to Liberia at all?

The last time I was there I was 10 or so. But, I’m supposed to go back next year to see my sister and brother. They still live there.

Have you tracked down your parents?

My mother passed away during the war and my father also did. I keep in contact with my sister, and that’s only recently. Growing up, these people were not in my thoughts. I tried to forget a lot of these things and just assimilate to American culture. It wasn’t until I was older that that guilt set in where I realized, “Man, I hadn’t even thought about anybody else in my country or the gift that it is to be chosen,” because it could have been my sister or brother that was chosen to come to America. I was just picked out of the group of them like, “Hey, he should go with this missionary family.” So, a lot of those things didn’t even come to my mind until I was older, to really see how much time I wasted absolutely doing nothing for anyone else but myself in this place. At that time, I was going through a lot of different vices and dealing with a lot of different bad things. I was constantly drinking and deep into my depression and lack of understanding of what my purpose was at all.

Or who you are.

I didn’t know who I was. I didn’t really know my past and history. I had glimpses of it from just some things my adopted parents had told me. But, I hadn’t dove into it until I contacted my sister and heard the real thing, the truth of it all. The goal is to go back [to Liberia] and try to get some colors from my native country and, and just, you know, spend some time with people that I haven’t seen in a long time and learn. The last time I went was really difficult. When I was there, it was in the middle of the second civil war and we ended up staying longer than expected because the child soldiers had taken over the capital city of Monrovia. It was a really scary time and that was the last memory of Liberia during the conflict. That’s a whole other cathartic piece of my journey, to [once again] step foot on that soil. I think once I step foot on that soil, I’ll probably weep. A lot of things have been bottled up and lodged into different areas of my body, [and will be] released onto the continent. But, not until I go there. My story won’t end until I go back. That’s a major piece.

You have such an interesting perspective, because I think a lot of times people in this country take things for granted, where they’ve either never traveled out of this country or they’re not from other countries. I would surmise that you probably see things that are beautiful in this country that a lot of us don’t acknowledge.

Yeah. There’s so much beauty in this country. Through all of the tirades against each other, there is still so much goodness. I mean, being able to walk out your door and be able to get anything you want at a store that’s there and not be–

Afraid to go for that walk.

Not afraid to go, yeah. Not afraid to go on that walk knowing I might not come home today, and there’s many countries like that currently. People don’t even have that freedom to go out their door and just see something and or go walk in the woods.

Or make an album.

Or make an album. It’s crazy to me that we forget so easily the good things when times are tough. And when times are tough, you think that the good won’t come back again. Man’s memory is so short and it’s really the plague.

That’s really what kills us all is that our memory is terrible. In times of famine, you never think good will come again. So, you lose hope. But, everything’s cyclical as well. Good comes back and hard times come again. And then you weathered the bad time before, but you forget that you weathered it, so you suffer. That’s us. That’s humanity.

Photo Credit: Glenn Ross