Nestled in the foothills of the Appalachian mountains 300 miles east of Nashville, the Virginia-Tennessee border city of Bristol has long been widely known as “The Birthplace of Country Music” — the mythical small town where the “big bang of country music,” as music historian Nolan Porterfield first called it in 1988, took place during 10 apocryphal days during the summer of 1927.

Due to its relative proximity to varying regions, from Asheville, NC, to the Virginia Blue Ridge Mountains to the Clinch Mountain ridge in Kentucky, the town of Bristol was where New York-based talent scout Ralph Peer set up an open audition in order to attract regional Southern talent to the fast-growing recording industry of the pre-Depression mid-1920s. Among the dozens of artists that showed up for the open call during that summer were Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family.

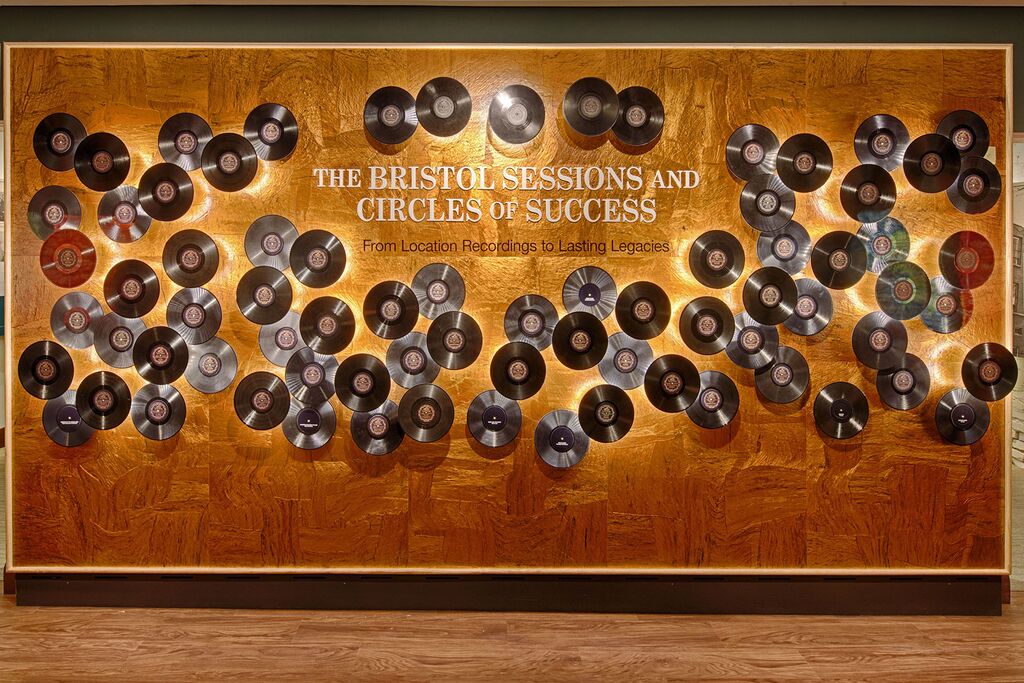

Nearly 90 years after the historic ‘27 sessions, the Birthplace of Country Music Museum opened in Bristol in the summer of 2014. The museum, which earned immediate affiliation with the Smithsonian, cost $11 million to build and is surprisingly expansive, devoted not only to the history of the ‘27 Bristol Sessions and the early roots of country and bluegrass music, but also to the history of the town of Bristol and the region at-large.

Here are some of the museum's highlights:

The Original ‘27 Newspaper Ad Announcing the 10-Day Audition

“Don’t deny the sheer joy of Orthophonic music,” begins the advertisement announcing Ralph Peer’s open audition. That phrase, Orthophonic Joy, was used as the title to a new album released earlier this year featuring artists Ashley Monroe, Vince Gill, Emmylou Harris, and Dolly Parton and Marty Stuart remaking some of the most famous Bristol Sessions material. “The Victor Co. will have a recording machine in Bristol for 10 days beginning Monday to record records,” reads the plainspoken ad. “Inquire at our store.”

WBCM Studio

One interesting facet of the museum is that it also functions as a fully operational contemporary radio station. WBCM Bristol Radio, an FM station that also be found online, plays a selection of bluegrass, roots, country, and old-time traditional music, and hosts a regular array of live studio performances and modern-day Radio Bristol sessions.

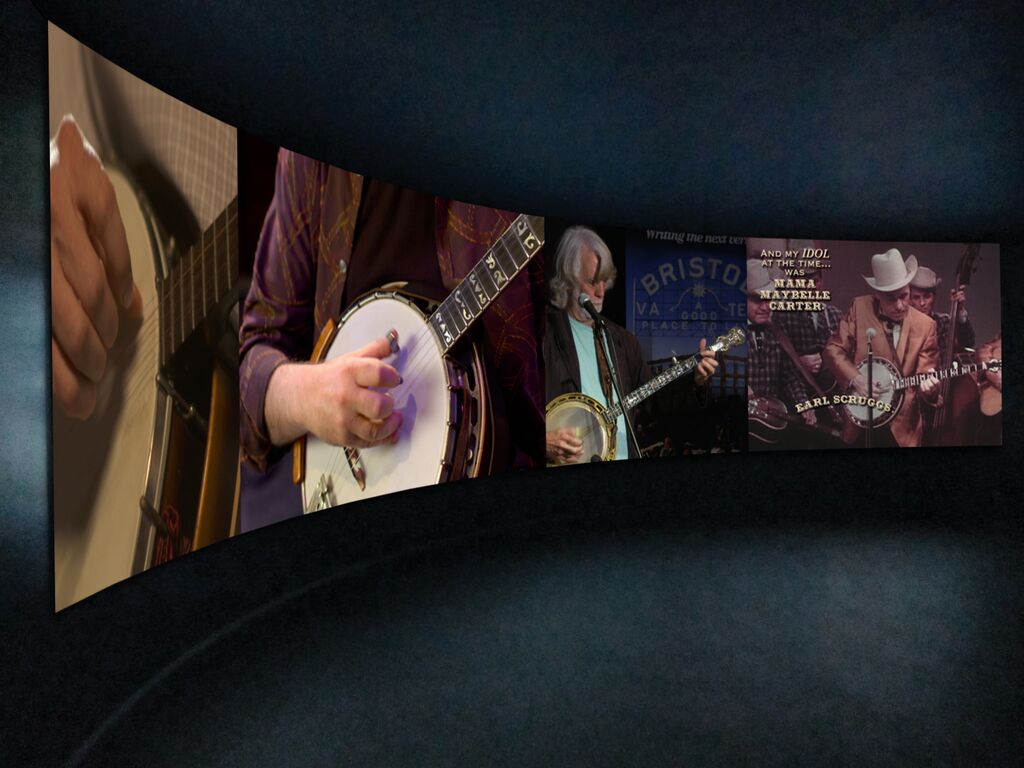

Recording Your Own Bristol Session

One of the silliest, most entertaining aspects of the museum is a recording booth where you sing your vocals over newly recorded instrumental versions of several original Bristol session tunes. You can even lay down an earth-shattering rendition of the Carter Family’s “Single Girl, Married Girl.”

Will The Circle Be Unbroken Short Film Immersion Theater

Toward the end of the museum tour, there’s a short film that is functionally an audio collage of countless different recordings of the spiritual “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” In the film, the song is performed by everyone from Faith Hill to Mavis Staples to Spirit Family Reunion and the Black Lillies. The film is, perhaps, the best example the museum has to offer of the wide-ranging, ongoing influence the original Bristol Sessions still have on music in the 21st century.

Johnny Cash’s Signed Guitar

Though his relationship to the central focus of the museum is arguably tangential, Johnny Cash forever became a part of Bristol’s musical story when he married June Carter, the daughter of founding Carter Family member Maybelle Carter, in 1968. One of the museum’s most star-studded artifacts is Cash’s Martin guitar from that very year. In addition to Cash and Carter, other country legends, including Bill Monroe, Waylon Jennings, and George Jones, have signed the guitar.

Mapping the Sessions

The museum nicely highlights the early 20th century music of not only Bristol, but, necessarily, its plentiful surrounding areas. One panel notes the individual home towns of each performer at the original 27 sessions who came from at least five different states, from Mississippi to West Virginia.

Segregating the Bristol Sessions

The museum does a particularly good job addressing the racial hypocrisy and discriminatory practices of the recording industry during the 1920s. Blues music recorded in Bristol by white artists like Henry Whitter were marketed as hillbilly records to mainstream white audiences, while similar-sounding recordings by blues player El Watson were marketed and distributed as “race records” to black audiences. Kudos, too, to the museum gift shop for selling Segregating Sound, Karl Hagstrom Miller’s fantastic book that outlines how the early 20th-century recording industry so often imposed harsh racial boundaries and segregations on the musicians and artists they recorded.

Bound to Bristol

John Carter Cash narrates a 20-minute film near the beginning of the museum tour called Bound to Bristol. The piece gives a fairly comprehensive overview of the story behind Peer’s recording sessions and touches on the importance and centrality to early country music of Ernest Stoneman, the hillbilly singer who encouraged Peer to record in Bristol.

The Hill Billies

One of the most informative panels of the museum is the one that explains the derivation of the term hillbilly as a way of denoting country/white rural music during the first half of the 20th century. Peer was recording a string band in 1925 and when he asked them for their name. They shrugged and said, “the Hill Billies.” For the next 20 years, country music would be marketed, distributed, and commercialized as “hillbilly” music.

The Birthplace of Country Music Museum is currently hosting an expansive special exhibit on the career and life of pioneering American roots singer Tennessee Ernie Ford. The exhibit runs until February, 2016.