People are dying. This is not a lie. Black women, men, and children are dying. You do not have to have the same skin to feel that pain. All across the nation the stories are appearing: murder, calling itself death, but murder all the same. The killing of unarmed black people by our law enforcement officers is murder. In the street we hear the demand for justice, for trials, for a future.

Even If you are not personally affected by the oppression that is killing black and brown people, you still have a place in this revolution. You have the ability to touch your peers and change the climate of opinion.

This is a call to all of you folk singers.

I am asking you to, as bell hooks says,

FALL IN LOVE WITH JUSTICE.

We must fall in love with human rights. We must bring love back into our culture. We must fall in love with celebrating the work of activists who are risking their lives for equality.

You must be willing to come to folk music understanding that your journey has not been the only journey that deserves to be shared, that your truth is not universal, that there are other stories not being told. You must understand that the history we have been taught is a selected history. You must simply bear witness, not to be a spokesperson, but to share what it is you have seen. You have a unique role as a travelling musician. You are a story teller. You have driven through the ghettos that some call home while some drive past with locked car doors. Share the humanity that has been elevated in you by the struggle that was once hidden and is now filling the streets. Help others understand what they may not understand. Help them open themselves to others’ experience. Help the listener realize that the media stereotypes they have ingested are not the absolute truth. Help them expand their consciousness. You have the power to spread the words of justice. Take an active role by helping amplify the voices of people who are doing such dangerous and important work. Help undo the racism we are taught. Help reinvent the future. We do not have to continue this way. But make room, because there are more voices who are coming to share the table.

Folk music is a tool. Folk music was social media long before the Internet. It was a way to spread the word about current events by the people for the people. Today we use social media to avoid the corporate bias of the news media. We have disconnected from the usefulness of folk music. We are betraying our time. We are betraying the ancestors we are influenced by. They were not super-humans to be idolized; they were people — fragile and real — who felt they needed to be free. They fought and they sang and they spoke out.

But as I look around today I see none of my peers saying a thing. There is a tendency to look back on the years of the Civil Rights Movement and romanticize, to idealize, and to then critique and place blame on the people in the streets today. This is where I feel so betrayed by the “folk music” of today. Where is the outrage? Where is the love of justice and freedom for all? If you are too afraid to stand up for people who are marching in the streets saying “STOP KILLING US” then you, friend, are not a folk singer.

What does folk music mean to you?

To me, it has always meant music that lifts the human spirit out of the terror and anguish of oppression. It is the sound of the strength of humanity.

Today, as it seems everywhere we look there are people of color, black and brown people who are voicing frustration, demanding justice and the right to live, I wonder: where are the musicians to sing the tune of this time?

Why does folk music mean so much to me?

There is a deep sadness in me when I think about how many of us remain silent. It scares me, and makes me feel like things have gone so far, like the machine has worked its power over us, and conditioned us to ignore the pain around us. Folk music is for John Henry, who can beat the machine with his own muscle and blood. Folk music is a song singing us out of the deafening silence of oppression and hatred.

But who is “us?”

Perhaps it is cultural white-washing that has taken the revolution out of folk music. Perhaps the prevalent idea that folk music is only meant for white heterosexual men (and a few women) is pushing away so many young revolutionary songwriters of color who feel they have no place.

As a folksinger, I have met with much appreciated critical acclaim this year. As a young Puerto Rican female, I have also been besieged by interviews questioning every part of my identity in the context of folk music. I have been asked again and again how it feels to represent “the voiceless.”

This term “the voiceless” is a blanket phrase used for anyone who strays from the white heterosexual normative. It is a term used for the people I come from, and not many know how frustrating it can be. People who experience oppression are not voiceless; their voices are simply not being heard. I’d like to offer a new term for “the voiceless”: “the unheard.”

What does it mean when we ignore people and then label them “voiceless?” What does it do to our collective psyche? I believe it conditions us not to listen to them. I believe it creates an environment where anyone who is an “other” is tokenized. When people of color are “allowed” into the world of modern folk music we are held up as spokespeople. We are thought to be special, unlike the “voiceless” others of our background. Though I am proud of my people and enjoy speaking about where I came from, perhaps some context and education is in order. No one enjoys to be treated as a token.

Being tokenized has made me — who always felt at home in folk music — suddenly become so aware of my difference. It made me feel alien in what was once a spiritual home: the warm embrace of singers like Odetta, Joan Baez, Lydia Mendoza, Harry Belafonte, Nina Simone, Buffy Sainte-Marie and Woody Guthrie. It made me feel like saying “You win. This is yours now. I will go elsewhere.”

If we as a whole became more educated about the way folk music has been influenced by people of color from all backgrounds then I believe we would have a more diverse group of musicians today adding their stories to the folk conversation. Over and over again I am amazed at the lack of education there is about women of color in the history of American music. It is a history that has purposely been rewritten again and again. If real history was understood and commonly taught, then the actions of protestors from Ferguson to Baltimore would be seen in their context of a long history of fighting for human rights. It is this context that creates a deep understanding of oppression, how far it reaches, and how intently it destroys the legacy of black and brown people. When we fight the erasure of our history, we become a little more free.

How dangerous for the future of folk music in our country it is to push away the people who could be telling first hand accounts, singing dreams of justice, and proclaiming their love of this land and all it could be.

As time goes on, we will continue to witness an upheaval, a call to action, a demand for change until black and brown people in this country receive justice. We will see who chooses to sing about what is going on outside their window. A bubble has been created; who will have the guts to pull a pin and prick it?

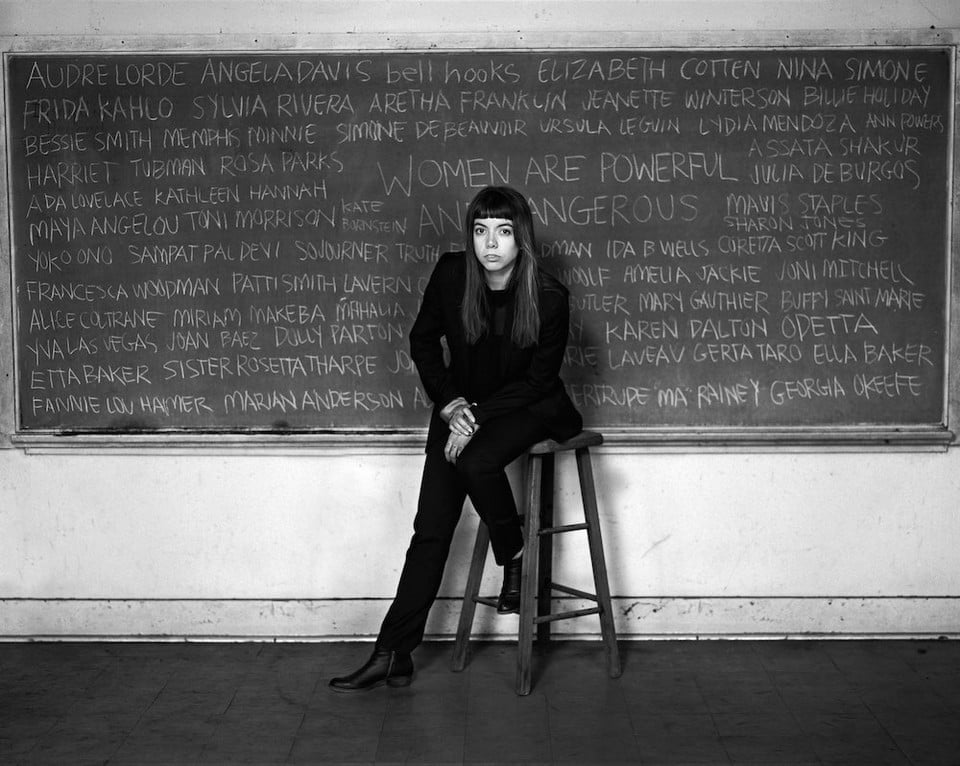

Alynda Segarra is the lead singer and songwriter of Hurray for the Riff Raff. [Photo Credit: Laura E. Partain]