“What’s the name of this song you’re going to sing?” says Herbert Halpert. The year was 1939, and the folklorist was visiting Elk Park, North Carolina, a small mountain community near the Tennessee border, not far from Johnson City. There, he met two singing sisters, Mrs. Lena Bare Turbyfill and Mrs. Lloyd Bare Hagie.

“’Lily Schull,’” replies Turbyfill.

“Were you used to singing it together, before … “

“Yes, sir,” they respond in unison.

“I mean … when you were young, did you sing together at all?”

“Ever since we’ve known it.”

Perhaps it is the 80 years between then and now, but those words sound an awful lot like forever when Turbyfill says them in her Appalachian accent. But “ever since we’ve known it” is 25 years at most.

“That’s the way you sing it most of the time?”

“Yes,” again in unison.

“Go ahead and sing it the way you do most of the time. Go ahead.”

It’s a perfectly awkward moment saved for all of posterity by Halpert’s disc-cutting machine, which he hauled down the East Coast collecting folk tunes. It’s city meeting country, urban meeting rural, educated meeting self-taught, but any discomfort is dispelled as soon as the two sisters start singing. They sing with no accompaniment — their voices blending almost magically, following no harmonic pattern other than the one they devised and perfected themselves. It’s the essence of folk music. Their sisterly harmonies and spry phrasing contrasts sharply with the grisly story of “Lily Schull” which, like so many murder ballads, begins in penitence and punishment. In the first verse, a crowd surrounds a jail to hear a condemned man’s last words. In the second, he confesses to the “murder of Lily Schull, whom I so cruelly murdered and her body shamefully burned.” By song’s end, he is asking God to save his soul and watch after the wife and family he leaves behind.

The sisters hesitate between the second and third verses. Perhaps they are overcome by the details of the crime, or perhaps they are responding to some gesture by Halpert. It’s a silence that asks, “Should we go on?”

Once the murderer meets his Maker, the folklorist asks the folk artists about the song. Turbyfill responds, “That’s a true song,” and the tape cuts off. Perhaps the sisters knew the story of Lilly Shaw, an African-American woman from East Tennessee, whose murder inspired “Lily Schull.” Perhaps they knew she had been brutally killed in 1903 by a man named Finley Preston, who was hung two years later after multiple appeals. They had learned the song when they were teenagers and, by the time they met Halpert, had been singing it more than half their lives.

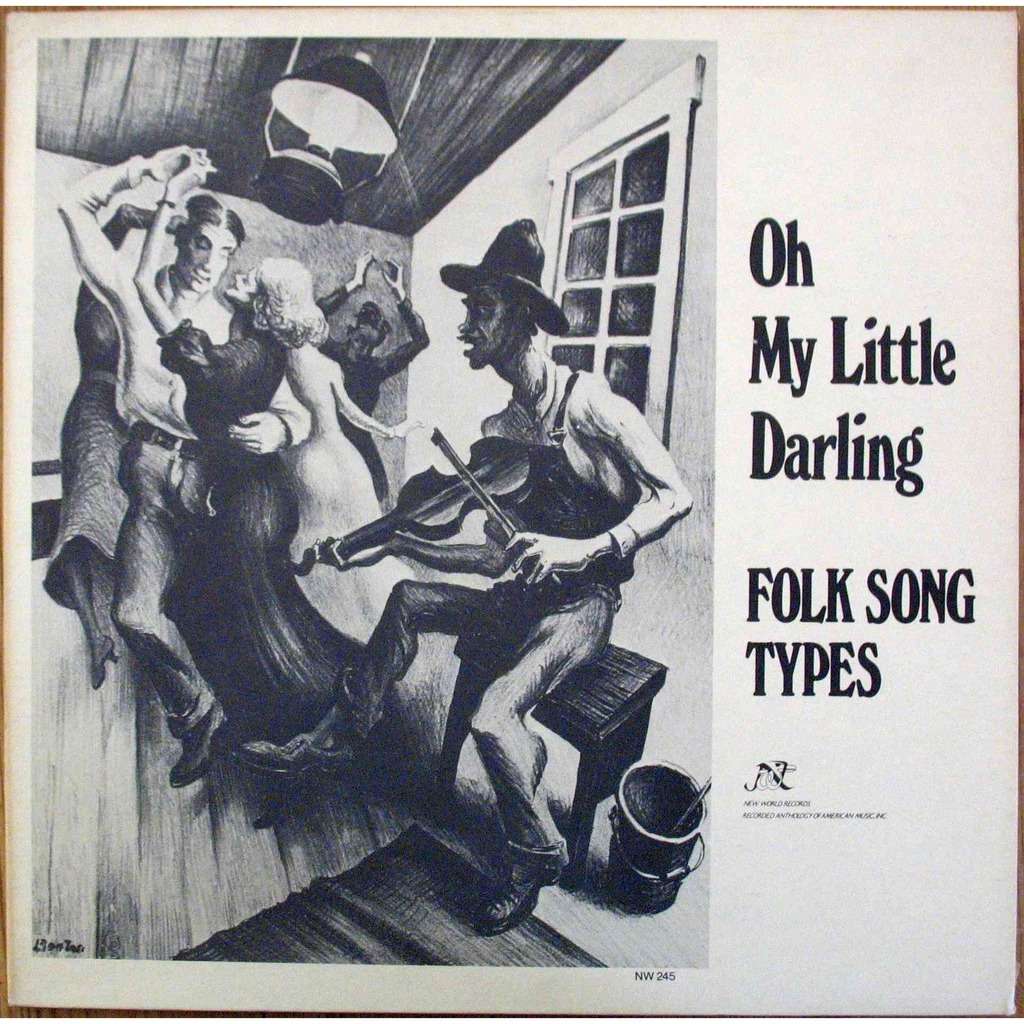

Forty years later as it was cut to disc, “Lily Schull” was anthologized on Oh My Little Darling, released by New World Records, a label established in 1975 by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to produce a comprehensive anthology of American music. There are many folk compilations like this one, far too many to list. Oh My Little Darling is nowhere near as beautifully strange as Harry Smith’s world-building Anthology of American Folk Music, nor is it as comprehensive or as immersive as the multi-volume Sounds of the South series. It lacks the geographic specificity of the 1975 anthology High Atmosphere: Ballads and Banjo Tunes from Virginia and North Carolina. It was only pressed once to vinyl, and reissued in 2002 on CD. (As of this writing, the compilation is not available for download or streaming.)

Regardless, Oh My Little Darling stands out as a useful entry point for newcomers to American folk music. Culling from various sources and covering a range of styles, it serves as something like a textbook to the various types of folk songs percolating in the American South during the first decades of the 20th century. It opens with Arkansas singer Almeda Riddle performing a children’s ballad called “Chick-a-Li-Lee-Lo,” perhaps the most famous song here. There are also cowboy songs and outlaw songs, minstrel songs and labor songs, bawdy blues and evangelical hymns, songs derived from old broadsides and songs known as Child ballads, collected by the 19th-century proto-folklorist Francis James Child.

In his liner notes from the 1977 vinyl edition, folklorist Jon Pankake warns against lumping these disparate styles into the same category, as though every folk song belonged to the same species. He would rather us celebrate the infinite variety of the music, which reflects the infinite complexity of American history. These songs document the fears and desires, regrets and prejudices of the past, serving as vessels of public memory, chronicles of history as it was experienced in rural America. History books don’t mention Lillie Shaw, but folk music memorializes her for generations.

In some ways, folklore, as represented by Oh My Little Darling and similar compilations, offers a rebuke to the Great Man school of history, established in the 19th century and still perpetuated today by such scholars as Joseph J. Ellis. That approach to the past suggests that all history is motivated by the actions of great and powerful individuals. Folklore relocates both the motivation and the documentation to the will of the people.

In that regard, this compilation is a fine introduction to American folk music as a populist force, especially if you’re looking to start a band. That’s what Jay Farrar, Jeff Tweedy, and Mike Heidorn were doing when they discovered Oh My Little Darling at the Belleville, Missouri, public library in the late 1980s. It opened up a new world for them and showed them how they might marry folk subject matter with punk guitars. The trio took the name Uncle Tupelo, and the roots of their debut, No Depression — not to mention the genre it inspired, also called No Depression, or alt-country, or whatever-you-call-it — twist tightly around these old recordings. The band would even cover two songs on their third album, plainly titled March 16-20, 1992 after the rough dates for the sessions in Athens, Georgia. Farrar sings both tunes in his grave baritone, turning “Lilli Schull” into a time-stopping mea culpa. The song plods along as he draws out each line, as though he’s trying to stall the snap of the noose around his neck. It’s a much more obvious interpretation than the sisters’ original, but still affecting in its deliberation.

Farrar also sings the 1937 labor song “Come All You Coal Miners,” written and performed by Sarah Ogan on Oh My Little Darling. This original is a cappella, her only accompaniment the hiss and crackle of the archival 78 record, and she sounds righteous and outraged describing the dangerous conditions miners faced at the time: “Coal mining is the dangerousest work in our land today,” she spits, “with plenty of dirty slaving work and very little pay.” She makes her closing line a rallying cry to presumably striking laborers: “Let’s sink this capitalist system to the darkest depths of hell.”

Farrar never had the humor or the audacity to sell such a line, but he nevertheless savors the historical details in Ogan’s lyrics. “I know about old beans, bulldog gravy, and cornbread,” he sings, as though the camp menu was a password to the union meeting. His version is more a lament, perhaps sung from the point of view of a miner who survived the pits yet still recalls the perils. Neither “Coal Miners” nor “Lilli Schull” resembles its original, which is the whole point: Uncle Tupelo understood that the class issues of the 1930s were pretty much the same as those of the 1980s, which empowered them to participate in that folk tradition and put their own stamp on these old songs. For that reason, Oh My Little Darling stands as a foundational text in alt-country and contemporary Americana — a testament to the malleability of American folk music in all its types.