Although he holds a law degree from George Washington University, Dave Stine certainly isn’t what you would call an office type. After a short stint practicing in Washington, D.C., Stine understood that the family farm in Dow, Illinois, was calling him back to what was always in his blood: family, friends, and, just as importantly, woodworking and furniture making.

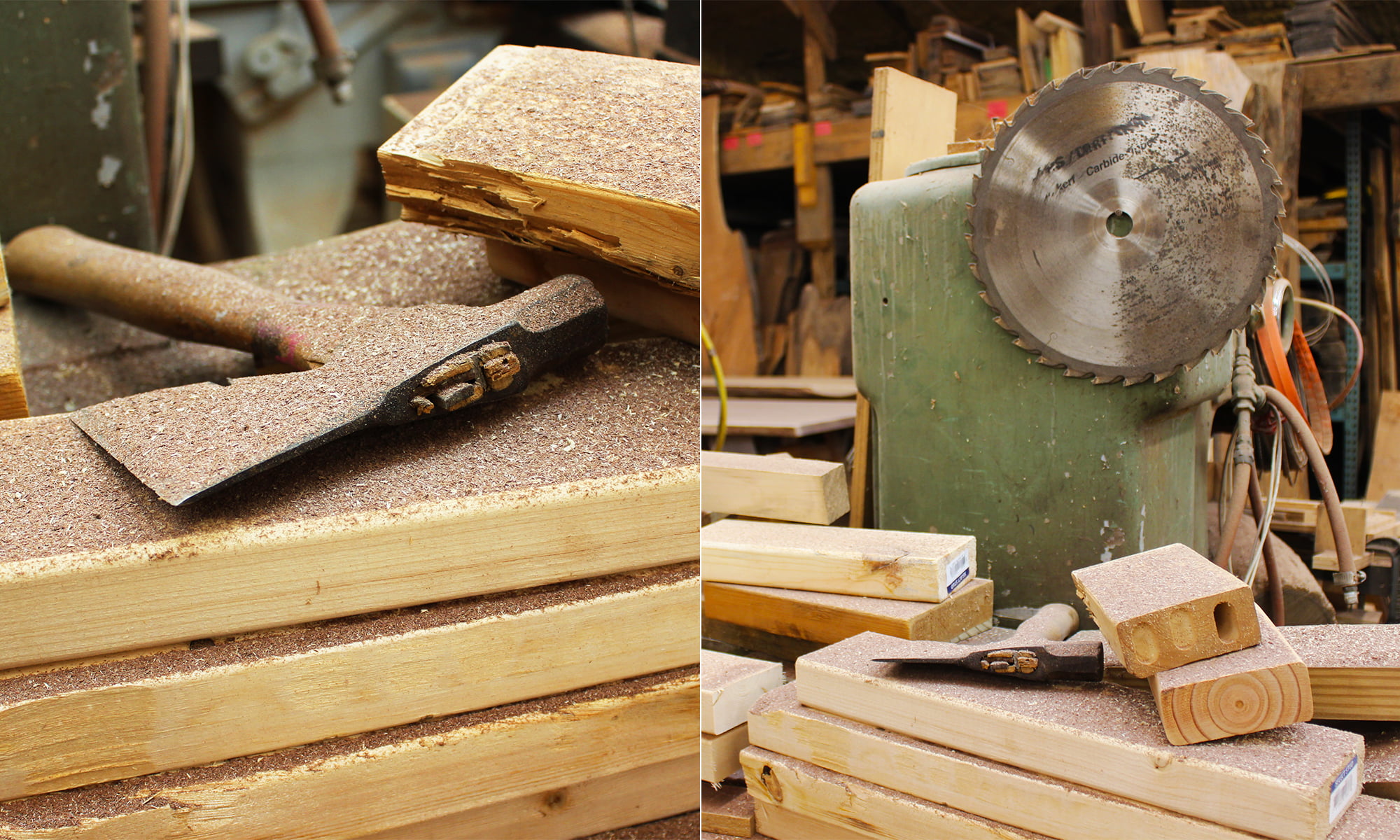

The farm spans four generations. Stine learned from part of these generations the art and precision of handcrafted designs and a love for the land that still ties the family together. Although a thoroughly American phenomenon, Dave Stine makes some of the finest pieces of furniture in the world. From tables to bed frames to whiskey shelves, Stine's live-edge work is exquisite, handmade, American — universal — beauty. An avid outdoorsman, Stine stewards his forests — over a thousand acres spread around Dow — and sees in fallen trees what Rodin might have seen in a block of dead stone: the potential in knotted trees and grainy, dead wood to possess beauty before and after he has milled and cut and worked out what is breathing invisibly within.

Stine’s clientele includes well-known names, household names even — Michael J. Fox and Andrew Sullivan to name a couple — but he seems much more interested in his day-to-day work within the shop just down the way from his home, and in those family members or comrades that visit or live on the farm and land. His clients respond to his work, to say the least … work done on the family farm. This isn’t a mere commodity. Stine adores what he does, knowing it’s good and true art he makes. He has intense eyes, like those of a wild, early explorer of America, the kind that can pierce through rhetoric and bullshit, yet he is inviting, kind. And, yes, Stine’s beard — long and thick — is something to reckon with. He is a giant in every sense of the word.

I wanted to know about the transition from law to woodworking. That gets mentioned or glossed over [in articles], but could you talk about why and how it happened?

Well, I grew up on the farm here. We always did everything here with our hands, from cutting lumber to making barns to butchering meat. You name it. So it was always in my blood to do that sort of thing. I’m the oldest in my generation, and my grandfather always pounded it into my head that I had to keep the farm going. It’s four generations, and we’ve got about a thousand acres, and it was always a big concern in my family. My grandfather always made it my problem. “You’ve got to know trusts, estates, taxes …” One of the reasons I went to law school was with that practical view in mind, being able to be able to do that kind of work for my family. And, also, school is awesome, and working sucks, so I stayed in school as long as possible …

Professional student?

Yeah. But all the way through high school, I was a diesel mechanic and put myself through college that way, and I was always doing a bit of woodworking on the side. But when I started in law school, I took a few tools with me. It was during that time when Cigar Aficionado was big, and everybody was into humidors and the whole thing. So, I started making humidors — cigar boxes — with locally harvested wood while I was going to law school. From there it just sort of blossomed. I finished law school, took the bar, got married, started working as an attorney in Washington, D.C. After 10 hours in the office, I’d put in four hours at woodworking. I’m not very good at office life. I don’t get along well with others. And it made sense. I already had a year’s backlog of orders, so it made sense to move forward with woodworking.

So you were getting orders while in D.C.?

Yeah. I was already doing a bunch of stuff with Georgetown Tobacco. Then I hooked up with some designers, and was doing spec and design pieces for them. Over the course of law school, I had gotten a shop space and had amassed a good collection of tools, so it’s funny: In D.C., not a lot of people work with their hands. They’re mostly attorneys or whatever. And so, if you can drive a nail, you’re busy — 24/7. It’ crazy! I had the capability of reproducing moldings, and there was a lot of gentrification going on. People were rehabbing turn-of-the-century houses, and I was able to make moldings and old-school window frames and screen doors and all that kind of stuff. But during that time, I was also doing the live-edge stuff, the stuff I responded to. I’d sell a piece here and there. But then it became more about furniture, live-edge, and it took off from there. But in the beginning, I’d take on anything.

What year did you come back to the family plot?

I started my business in D.C. and started doing it full-time in 1996. But we came back here in 2002.

What’s the process like as far as discovering the “right” tree, and discovering the piece that resides within it?

It starts out with a big piece of luck. I try to get to the forest as much as possible. It’s peaceful, it’s calming, it’s good exercise. It’s nice to get out of the shop and off the computer. I try to look for trees that are dying or dead or blown over by the wind … damaged. We have a lot of straight-line winds or tornadoes around here, so I just try to find stuff that’s already past it’s useful life, and then try to make something beautiful. I don’t cut down a perfectly living cherry tree. Some of the trees are young and have just fallen over or died; and some are just giant and have lived past their prime.

We have a naturally occurring forest. When you cut into some of these big trees, you can tell what kind of a life they’ve had. There are scars. There are knots, twists, and breaks that have healed over time. They have character to me, unlike that flat type of Ikea sort of stuff where everything is very uniform. What makes the wood interesting is kind of what makes people interesting: You’ve had scars, experiences, damage, and you’ve overcome it. That’s interesting. I’m lucky to be born into this family. If a storm comes and blows over a tree, you have to pull it and bring it to the shop, and then saw into it. That’s the first part of the process. Once you begin sawing, you’re committed to what’s there.

Is it sort of like sculpture in that way?

It might be. It’s another medium. I could see it like a piece of stone with different things running through it. With a tree, you might have a crotch or a split or knot, but those actually might be things you want to work with or emphasize. Once you make that first cut, you’re in it. You’ve got to have the courage of your convictions. Maybe it’s flat and needs to be a table-top. Maybe it’s wilder and sticks in your mind. I’ve had pieces of wood for 10 years that might be waiting for the right client. But you take what the forest gives you. I mean, the really radical ones stick in your mind. Maybe three months ago, I did a show in St. Louis. A guy took my card. He called sixth months later. He’d had my card, and the piece that he wanted was perfectly suited — a headboard — was perfectly suited to a tree I had cut down over 20 years ago. I’ve had a lot of lumber sitting around here, so it looks like a fucking bomb went off. It takes two or three years to dry. I don’t wait for a client to work. I stockpile material and wait for someone to desire it.

You can’t remember not working with wood. What’s an early memory of an early piece or even your first piece?

I was heavily involved in FFA and 4-H. We made shadow boxes and candle holders. I think the first piece was for a 4-H project. It was a toolbox. It was a harbinger. When you walk around the farm, I can see my grandfather’s hands on everything, my hands.

Photos courtesy of Jill Maurice / Final photo courtesy of Dave Stine