No one really knows who actually watches Today in Nashville, a newsmagazine show that comes on at 11 am and usually includes segments featuring local chefs making seasonal cocktails, barbeque tips, and probably a few cute and/or furry pets. It’s the kind of program that makes Nashville still feel like a small town, full of random snippets and Southern quirk — something nearly prehistoric in the post-Trump, Twitter-rage-filled America, where a quaint five minutes dedicated to, say, an ice cream truck, strikes as indulgent. Who tunes in to that sort of thing? Well, Jason Isbell, for one.

“I get a big kick out of this show,” says Isbell, calling from his home in the country right outside of Nashville, where he’s been watching: This morning, he learned about peanut-free day at the ballpark and squat techniques from Erin Oprea, Carrie Underwood’s trainer. “They just try to fill the space with local Nashville color every day, and it just cracks me up.”

It makes sense, really, that Isbell is drawn to Today in Nashville — there’s perhaps no better working student of local color, in all its permutations, than the Alabama native, who released his most recent album, The Nashville Sound, last month. It’s a collection of songs that don’t take the gifts of humanity at face value: love in the context of death, privilege amongst suffering, hope in a world on a collision course with an irreparable future. Much has been made about this being Isbell at his most “political,” but, really, it’s an LP that studies the causes and not the effects. Isbell is a listener, not a screamer, and as the Trump era has divided the country more than ever, he’s looking to understand why we got here, and not just point fingers. Isbell’s characters might be wanderers in small towns or coal miners looking for peace at the bottom of a glass, but he’s more interested in what he might have in common with them than what he doesn’t.

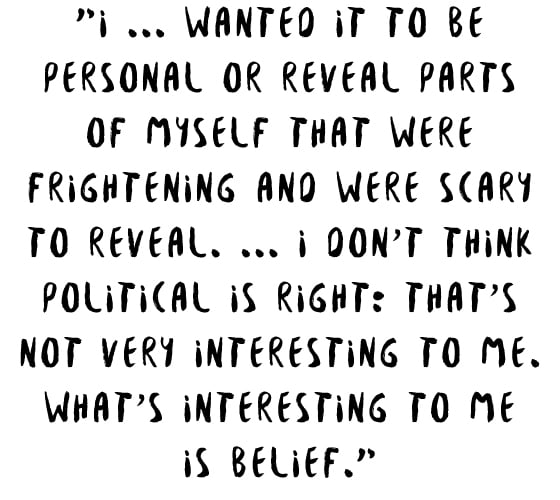

“This album, I wanted to stay away from a lot of the same type of reflection I did on Southeastern,” Isbell says about his breakthrough LP, which was followed by 2015’s Grammy-winning Something More Than Free. “But I also wanted it to be personal or reveal parts of myself that were frightening and were scary to reveal. And that came across in songs people might describe as having a political slant or agenda. I don’t think political is right: That’s not very interesting to me. What’s interesting to me is belief.”

“Belief,” after all, is a potent potion — especially since beliefs are often digested outside of a moral code. Isbell hasn’t been shy on social media about his stance on Mr. Trump’s policies (Spoiler: He is not in favor of them.), but The Nashville Sound is not the work of just an angry man; it’s the work of one who knows that human beings are complicated, confusing things who don’t always make the right choices, but not always for the reason you think. It’s a challenge to both criticize and empathize at the same time, and that’s what Isbell can do so artfully, by finding freedoms amongst flaws.

“Writing songs about race and gender, that’s a minefield,” says Isbell about tracks like “White Man’s World,” which take an honest stock of the privilege bestowed upon people simply born a certain skin color and sex. “One false move, and I am a laughing stock. One tiny little ignorance of privilege, and I am screwed. So you have to be very, very careful. And careful in a way to represent yourself correctly. You have to start out believing in the right things, and then you have to tell people that in the clearest way. That’s a great exercise, but it’s scary.”

On “White Man’s World,” Isbell doesn’t just try to offer apologies to people of color or to women — he takes it one step further. And that’s by admitting that there are layers that he doesn’t see, bias he might not even realize: “I’m a white man living in a white man’s world,” he sings. “Under our roof is a baby girl. I thought this world could be hers one day, but her mama knew better.”

That baby girl he sings about is Mercy, his daughter with wife and 400 Unit bandmate Amanda Shires. The album, produced by Dave Cobb, isn’t a “dad” record, but it is shaped by Mercy’s existence, and by the litmus test she adds to Isbell’s life. His marriage is also confronted, but, once again, in an unusual context: On “If We Were Vampires,” Isbell looks at love as something that can only exist within the sands of an hourglass. “It occurred to me that it’s a beautiful thing, death, if it happens when it’s supposed to and not a minute sooner,” Isbell says. “There is nothing else that would move us, if we didn’t know it was going to end. I wouldn’t be in a hurry to find somebody to spend my life with, to have a child, or work. I wouldn’t have any motivation to do anything — make art, get up off my ass, whatever. That’s really the point. People call it a sad song. Yeah, it’s a sad song, but sometimes people use the word sad to mean moving.”

There’s no doubt that Isbell’s a lyrical master — like the best songwriters, he blends prose and poetry in the most delicate balance — but part of what makes his work so captivating is that idea of what is “moving” over simply just sad, or any base emotion. The Nashville Sound gets this feeling across often by asking questions as much as it gives answers: Why does happiness breed so much discomfort? Is there any peace in knowing that death will come? What can we do, in this short life, to leave the world a better place than we found it? Rather than get purely political, Isbell aims to move minds, and to challenge beliefs that are held dear, through subtler storytelling and not just through enraged diatribes.

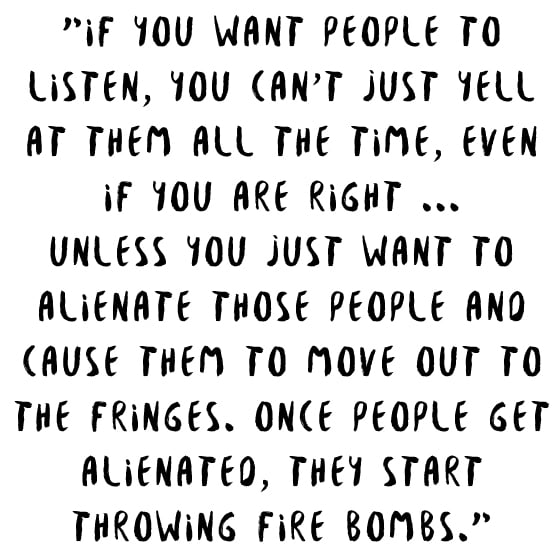

“If you want people to listen, you can’t just yell at them all the time, even if you are right,” he says. “If I am arguing with someone who is a hardcore conservative, I might think this person doesn’t realize how offensive his or her beliefs are, that they are racist or sexist, but you can’t just start screaming ‘You are a racist and you are sexist,’ unless you just want to alienate those people and cause them to move out to the fringes. Once people get alienated, they start throwing fire bombs.”

That sense of alienation is a lot of what built the Trump agenda, and, now, Isbell feels alienated, too. He’s confused by a country that could overlook “deplorable behavior” like Trump’s. “I thought I knew more about Americans that I did,” he says, talking about “White Man’s World.” “Having grown up in a small part of a Southern state and traveled for nearly 20 years, I thought I knew more than I do about American people.”

Of course, Isbell wants to know them as much as he can — it’s whyThe Nashville Sound is the number one country (and rock) record on the Billboard chart. You don’t appeal to both red and blue without reminding the audience that you’re not just preaching to them, you’re hearing them, too. And Isbell is listening to the Nashville sounds, as much as he is making them.

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.