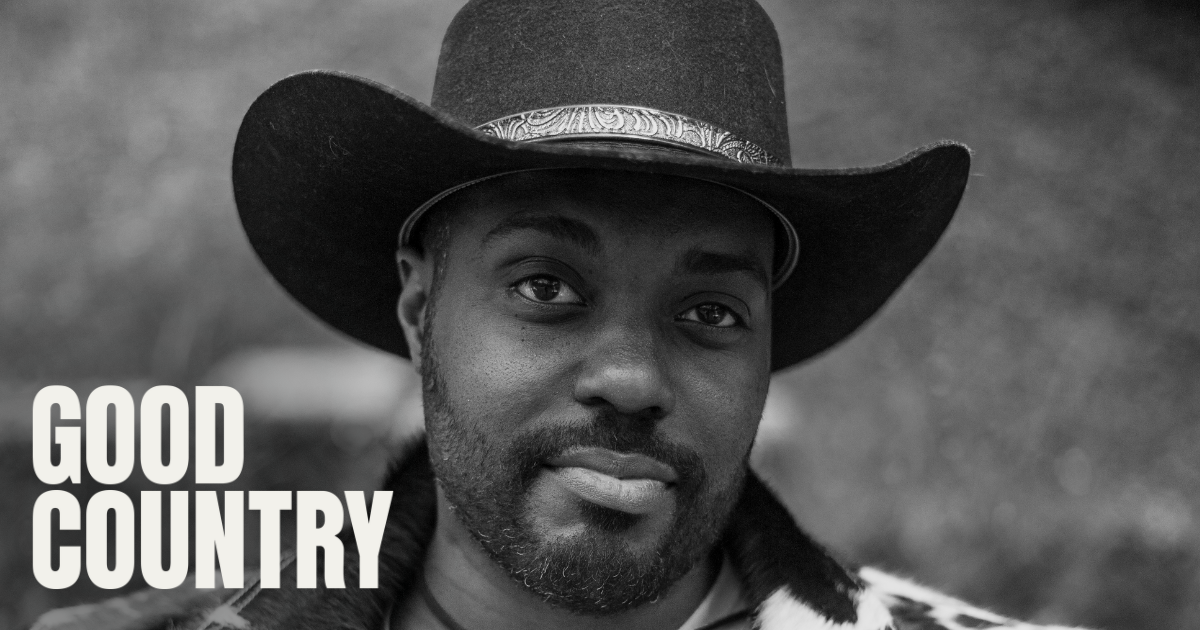

For years, Jett Holden dreamt and dreamt about making a living through music, but everywhere he turned he was met with doubt, subtle prejudice, and closeted racism that left him running on empty and searching for something new.

Following a journey to rock bottom, Holden is back stronger than ever on The Phoenix, a 10-song collection that catalogs his rise from the ashes and spotlights the community that embraced him when it seemed nobody else would. Told through a mix of countrypolitan, rock, punk, metal, and R&B sounds, the record is proof that there are no boundaries to who, where, and what good music can come from – and that we all benefit from everyone having a seat at the table, sharing their stories and perspectives.

“This album reflects who I’ve been throughout my entire life,” Holden explains to Good Country. “It’s been really cool to look back on when and where my different influences come from while bringing these songs to life. For example, ‘Karma’ is definitely Paramore meets Stapleton, while ‘West Virginia Sky’ harkens to my Tracy Chapman and Jim Croce influences.”

Fresh off a move to Nashville, Holden spoke with GC over the phone about the doubt and prejudice he’s faced along his musical journey, his work with the Black Opry, using music to heal past trauma, and more.

There’s a lot going on in your song ‘Scarecrow,’ from exploring your family’s reaction to coming out to masking the crippling weight of other’s doubts of what you’re capable of – along with a slew of Wizard of Oz references to the scarecrow, tin man, and cowardly lion. Mind sharing how all those ideas coalesced into one?

Jett Holden: It’s the first song I finished for the album. I wrote it back when I was 25, and at that point my family and I didn’t really have a personal relationship. It had gotten to the point where I came out 10 years earlier and wasn’t sure where I stood with them. I wasn’t disowned, but I also didn’t have anyone to turn to – they all pretty much told me they didn’t want to hear about it. I didn’t want to keep living in limbo, so a few years later I skipped town and moved to East Tennessee, which is where [Black Opry founder Holly G] found me in 2021.

You also had a brief stint living in California around this time that left you on the brink of quitting music for good. What all transpired out there?

I moved out to Long Beach after dropping out of community college. I was in talks about a development deal and during the “get-to-know-you” phase I let it slip that I was gay and they responded by saying that I wasn’t marketable as a Black, gay man doing the kind of music that I wanted to do. Things fell apart from there, which is why I left California and moved back to Virginia before eventually relocating to Tennessee.

Aside from that moment, were there any other circumstances that contributed to you feeling so defeated about your music prospects?

When I first moved out West, there was a very steep trajectory that isn’t common for most people, but it quickly deteriorated after I mentioned being gay, making for a really high peak and a really low low. When I returned to Virginia things got stagnant and didn’t progress at all, even moving backwards at times. It was a frustrating time of trying to figure myself out that culminated in the move to East Tennessee where I was roommates with a close friend before coming home one day after she committed suicide.

Another of my friends got cancer around the same time and just recently passed too, so those were very traumatic years for me.

By 2020, I just couldn’t do it anymore, so I started going to therapy right before the pandemic hit and the world shut down. Suddenly [music] was just too much to deal with, so I stopped making it. Being online was toxic so I shut down, got a stay-at-home job with AT&T, and accepted that as my future, working my way up in the company.

Then Holly — and the Black Opry — came around?

Exactly. I’d already called it quits when she found me on Instagram through a video I’d posted of my song “Taxidermy.” I only had that and a couple other covers posted, but it was enough for her to take interest and slowly pull me back into the industry. A couple months later she launched the Black Opry as a blog and it’s crazy to see where things have gone since then.

Within a year I’d gotten to tour all over the country, appear on The Kelly Clarkson Show, and I recorded my first single and EP through a grant I received from [Rissi Palmer’s] Color Me Country. Holly has made so many things possible that had been unavailable to me for my entire career until then, fighting for me in ways nobody else had before. She took chances because she wasn’t an industry person, but rather a flight attendant who was just a fan of country music and wanted to feel connected to it and the artists she was listening to, which is something a lot of others were in search of as well.

When I went to the first outlaw house she threw at Americanafest in 2021, I was expecting a bunch of Black country fans to show up, but it was also the queer community, the Latin community, and the women in country music that didn’t feel like they were getting a fair shake of things. Everyone who felt “othered” in country music showed up and it felt like immediate family. Seeing the excitement around that is what drew me back in.

Speaking of your song “Taxidermy,” I remember you being brought to tears while singing it during a Black Opry panel at Americanafest that same year. What’s that song meant to you, both in its message and what it’s meant to your career?

That song relaunched my career essentially, because I wasn’t chasing music when I wrote it. In fact, when I posted it online I only had one verse and the chorus. Despite it not being complete, Holly still sent it off to Rissi Palmer and got me the grant and I finished writing it the day we recorded. It’s a song of frustration that I didn’t expect many people to watch when I posted it, but Holly really connected with it, spread it around, and helped it blow up into something bigger than I ever imagined.

I was just singing about my frustrations with what was going on around our country at the time concerning police brutality, which was a big reason why I quit social media and music altogether in 2020. Instagram was the [only] online account I had when Holly found me. That song allowed me to vent about those things, but it also helped me gain the community I needed to break myself out of the news cycle that we were constantly absorbing, because we had nowhere to go. The song came about out of all that negativity, but had a huge positive impact on me that I never expected.

In addition to the support you’ve received from the Black Opry, you’ve also got a helluva team behind you for this record including the folks at Thirty Tigers, [producer] Will Hoge, and collaborators like John Osborne and Charlie Worsham (“Backwoods Proclamation”), Cassadee Pope (“Karma”), and Emily Scott Robinson (“When I’m Gone”). I imagine that, after everything you’ve been through, having folks like that working alongside you is incredibly validating?

Definitely! Emily was the first person I asked, since she was a very early supporter of the Black Opry. We both connected over “When I’m Gone” and our similar stories [around] suicide, so it was a no-brainer to have her sing with me on it. Holly ended up reaching out to Cassadee after I mentioned wanting someone similar to Hayley Williams featured, and she nailed it. It’s very cool seeing all these people I’ve looked up to legitimately wanting to work with me. I still haven’t met Charlie or John, but it’s wild knowing that they’ve heard my song and wanted to be involved in it.

Regarding “When I’m Gone,” is that a reference to your friend in East Tennessee that you walked in on after committing suicide? If so I’m sorry for your loss, but I love how you used the song to memorialize them and bring attention to the plight of suicide. It’s an awful thing to experience, but putting your feelings from it to song is a great way to bring beauty to an otherwise unimaginable situation.

You’re completely right. When I play songs like “When I’m Gone” or “Scarecrow” live I always have people coming up to talk to me about them afterwards, whether it’s someone who’s come out, dealt with religious trauma, or a person who’s just lost somebody close to them. There’s something very cathartic and heavy all at once that’s led to a lot of crying, but more importantly a lot of growth. It’s been great feeling like I’m not going unheard – which I did for over a decade – and having interest in what I’m doing where there wasn’t any before.

We’ve talked about a lot of the trauma captured in these songs, which brings me to the album’s title, The Phoenix. Is that reference meant to reflect how your life — specifically your musical dreams — have been reborn in recent years?

That was the intention. It was about the resurrection of my career, plus I also referenced the phoenix in “West Virginia Sky,” so it felt appropriate. Then, weirdly enough, just after recording the album I had a friend, also named Holly, give me a phoenix bolo tie for Christmas. It was a very kismet occurrence and a sign that that was the correct title to move forward with on the project. It makes for the perfect project, one where I have creative control and wrote every song (besides co-writing “Backwoods Proclamation”). I put my heart and soul into it, and am really excited for people to hear it.

If you could go back in time to speak with yourself when you were about to call it quits, what would you tell them?

Prioritize the relationships you build, because those are the people that will help you get to where you are supposed to be.

(Editor’s Note: Sign up on Substack to receive even more Good Country content direct to your email inbox.)

Photo Credit: Kai Lendzion