A queer Jew from Brooklyn seems like the most unlikely candidate to front a country band, right? If you factor in Karen Pittelman’s past experience singing and performing punk and queercore, her current old country-influenced, honky tonk-inspired group, Karen & the Sorrows, seems even more implausible. Addressing these kind of assumptions about who “owns” country or who is allowed “admission” to country — by the mainstream country machine, country radio, country writers, or country fans at large — is why the following conversation is so important. On the surface, it would be easy, even hackneyed, to presume that Pittelman and company came to country as opportunists on the waves of the Americana tide. But considering LGBTQ+ identities and perspectives in roots music necessitates digging deeper. Doing so in our laughter-filled dialogue with Pittelman was both enlightening and encouraging.

Before Karen & the Sorrows, you were singing in a punk band. I wonder how you bridged the gap between punk and country — it sounds like it was something of a homecoming for you. Did identity play into you leaving country behind? Did you feel that in punk you would be more free to be yourself rather than in country?

Yeah, I think that that’s true. I came up around queercore, a place where making music and building queer community are all one thing. But I also think the distance between country and punk isn’t as far as people like to think. Who’s more punk than Johnny Cash? Johnny Cash is punk as fuck. I think, in terms of genres that give you a space to tap into anger and make something out of that, punk and country are two of the best. Punk isn’t so good for heartbreak and that’s what took me back to country. Really, what I love the most are sad songs. My heart was broken and, I dunno, I guess when my heart breaks, pedal steel comes out. [Laughs] Different things happen for different people’s hearts, but that’s what’s in mine, so I had to come back to country, whether I wanted to or not.

What was the beginning of country for you? Did you grow up listening to it?

I guess I’m not the average country music listener. I grew up in New York City. Being a queer Jew, I’m not whatever is supposed to be the stereotype of a country music listener. [Laughs] I think lots of people who love country music don’t fit the stereotypes. My dad, when I was growing up, ran a company called Heartland Music and he made compilation albums that were sold on TV. He was working, through my childhood, mostly with country music stars. He would be making these commercials with Conway and Loretta, and George Jones, and Don Williams, and then come back home and play me everything — and force me to listen to everything and learn it. I was kind of resistant, but it all sunk in. I guess it was just in there waiting to come out later.

I always find it interesting that a lot of people who might be opposed to LGBTQ+ rights feel that, because these identities are becoming more visible in more traditionally conservative spheres — roots music, country, bluegrass, old-time — that people with othered identities are “infiltrators.” But when I have these conversations with diverse people, their stories are exactly analogous to anybody else’s experience getting into these genres. Where do you think this disconnect is happening?

I think that’s a kind of stance that happens not just in this situation, but in a lot of different situations where people are feeling afraid of anyone who feels like an “other” to them. Not just LGBTQ, but anybody who is outside of who they define as their community. It always feels like people are infiltrating, because the “others” feel scary. Almost always, whoever is being termed the “other” has been there all along. Especially in America, we’re all mixed up with each other whether we understand it or not. Depending on where you live, maybe things are less racially or religiously diverse, but you don’t have to travel very far before that changes. And certainly you can’t get away from LGBTQ people; we’re everywhere. We’re 10 percent of the population. So, whether someone realizes it or not, we’re always there. We’re your friends and your community. Maybe that makes it even more scary — people having to redefine who they are and who they think everyone else is in relationship to themselves.

I think that’s what I grapple with the most in trying to unpack these issues with people who may stand in opposition. Because of the way the narrative has been told for so long, it’s easy to think that these ideas have only cropped up in the past 30 to 40 years. It’s hard to undo the revisionist history that everyone holds so closely, because it’s a linchpin to their worldview.

When the history of queer people in music is erased, of course nobody knows that it’s actually there. Queer people have been making all kinds of music all along, of course. If you’re not used to hearing that, I get it. You’ve been told your whole life that somebody is the enemy, that somebody is dangerous to you because of who they are — no matter how you define that “other” — you’ve got a lot to disentangle and unpack before you can see me or somebody else as a fellow musician, your neighbor, your friend, or your family.

I noticed, when I first started reading about your band and your album, that you’re clearly labeled and tagged “queer country.” In the course of these interviews and conversations, I’ve found a whole continuum of visibility and display of artists’ identities in what they create. I wondered how you got to the point where you wanted it to be overtly queer?

To me, first and foremost, it’s about the music. First, second, and third it’s about the music — and I just want people to hear the music. As a woman, though, I already don’t get to have that luxury (of being less visible). It’s already going to be, “Ah, women in music.” [Laughs] It happened because I was just craving the space for queer country to exist and I so missed having that space in queercore and queer punk shows. Not that queer space is the only space that I can feel comfortable in or the only space I want to play, but it really feels like home to me. I felt like I needed to make that space for myself and then other people, too, especially when other people were saying, “Yes! We need this, too.” That inspired me and made me feel like I had to keep going. That’s how we started calling it queer country.

Obviously, like we were just talking about, queer people have been making country all along — we’re going to play our record release show with Lavender Country and Patrick Haggerty made his out, proud, queer country album in 1973! I needed this community and, in order to make community, you have to be willing to announce it. “Okay, this is going to be queer country and that’s who we are and anyone else who feels the same way, come play this show with us!” [Laughs]

I can totally relate to that. I grew up in bluegrass — traditional, straight-ahead bluegrass. I didn’t realize that I craved a space to be queer within bluegrass until I tripped into such a space. You feel this burden lifted that you didn’t realize you were carrying around, just from feeling like the odd person out. It feels so good!

Especially in the way that roots music wants to claim a sort of “home” — a space where everyone can feel welcome, where it isn’t about putting on some kind of airs. This is music that’s about telling the truth about your life, about telling the truth of who you are and where you come from, so it’s important that we’re creating a space together where our lives feel known. I think it’s hard to realize, when you grow up with a certain kind of music, that you’re not being included in it. You know, but you don’t know in your bones, until you’re in a space where you are included. Then you realize how lonesome it felt all along.

That really resonates with me. It feels like the LGBTQ+ community in roots music is starting to network and weave together this strong fabric with each other. I love that.

I feel like we’re making it together right now! It’s amazing!

I want to ask you about “Take Me for a Ride” off of your new record, The Narrow Place. I love that it’s basically bro country, but queer. While listening to it, though, I could imagine someone hearing the lyric “I wanna kiss that pretty mouth and keep on kissing south” sung by a woman to a woman and being appalled by how “inappropriate” it is. Meanwhile, Sam Hunt’s “Body Like a Back Road” has been at number one for a record-breaking 25 weeks!

[Laughs] Yeah, “Body Like a Back Road” is way dirtier! It’s funny: I wasn’t sure, when I was working on that song, how dirty it would end up being, but I knew what I was going for. I think it ended up pretty sweet, as far as saying dirty things go! [Laughs] But “Body Like a Back Road” is filthy! And so catchy.

So how do we bridge this logical gap for people? We talked about this a little bit before — queer people have always been in country; queer people come to country music the same ways as everybody else. How do we show people that don’t want us to “flaunt it in their faces,” that it’s really not any different than Sam Hunt singing about “driving with his eyes closed”?

[Laughs] Hmm. I had this really interesting experience with someone writing a comment on one of our videos on YouTube. They wrote this really nice comment about how much they love the song and the band, but then they basically said exactly what you just said: “I don’t understand why you have to be putting all of these identity politics and labels on things.” I wrestled with it for a while, but then I wrote back saying, “Thank you so much. You know, I wouldn’t describe it as ‘putting labels.’ I would just say that all of my favorite country music and musicians just try to bring the truth of their lives to the music.” The person wrote me back saying, “Oh, I get that. Thank you for taking the time.”

Now, obviously, it doesn’t always go like that! [Laughs] That was like the world’s best case scenario of that conversation. He felt heard, I felt heard, everything went great. I mean, why do you want to hear Tim McGraw and Faith Hill sing “It’s Your Love”? It’s because they love each other! For real and in real ways. It’s beautiful, and you feel the truth of it. Yes, there’s an entirely different question here of how authenticity gets constructed. It’s complicated. That said, I do believe in bringing your truth to the music. If we all agree that that’s something we love about country music, then we’re going to need to find a way to let everybody who makes the music bring their truth.

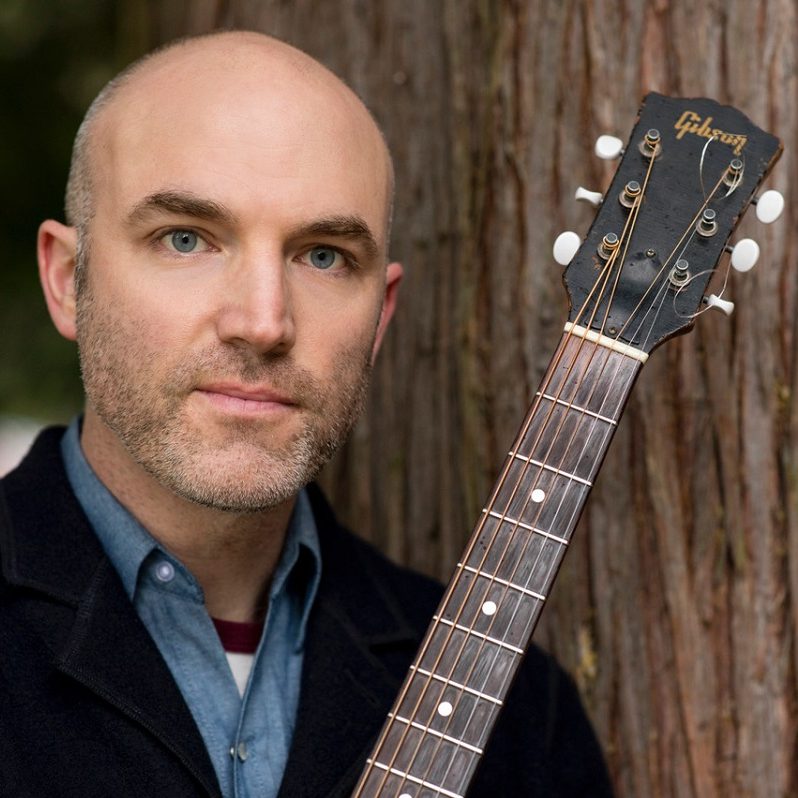

Photo Credit: Carole Litwin — (from left to right) Tami Johnson, Karen Pittelman, and Elana Redfield