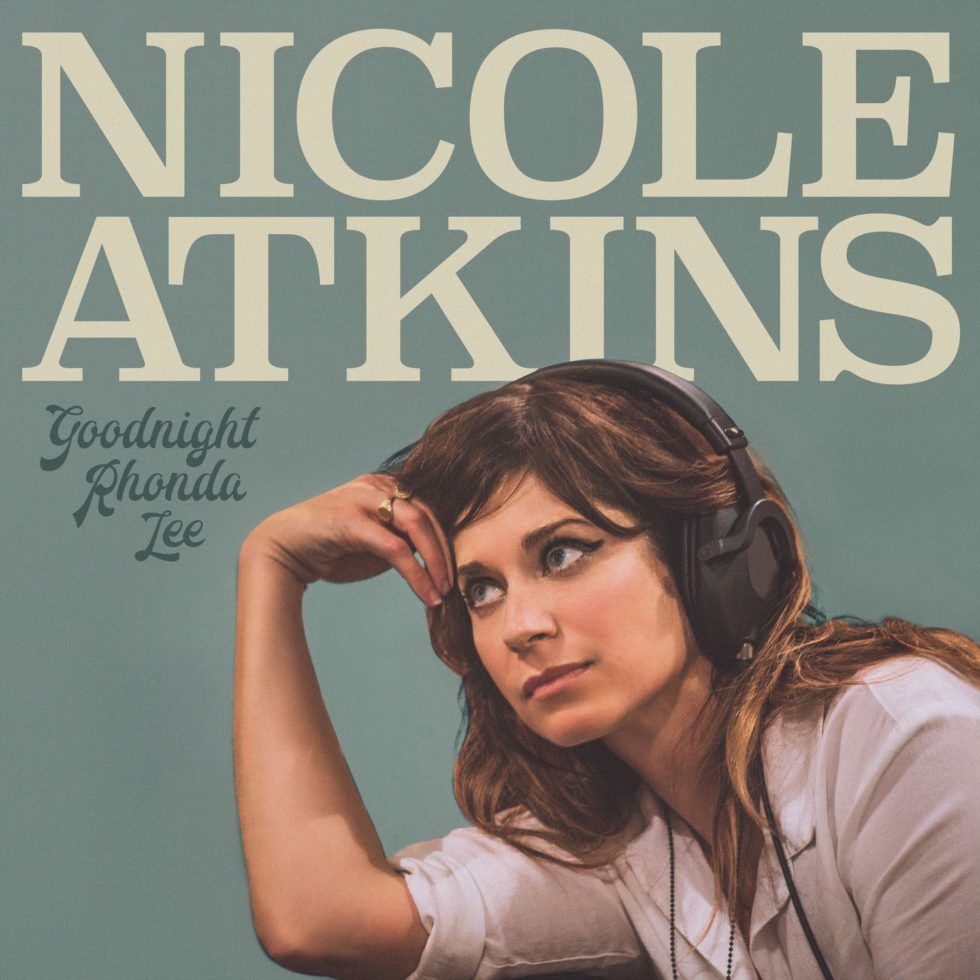

She knew the session would be worth documenting, but at the time, Nicole Atkins didn’t realize that the cover of Goodnight, Rhonda Lee would be a shot of her soaking up one of the most difficult songs she’s ever written.

On the night they recorded the string parts for “Colors,” Atkins invited Griffin Lotz — a longtime friend of the Jersey native and a Rolling Stone photographer — to hang around the studio and take a few pictures of her and the guys in action. At one point, Lotz trained his lens on Atkins listening back to the somber strings that accompany her dusky voice and Robert Ellis on the piano. Atkins’s eyes recall the Atlantic waves that wash upon the shore that shaped her, a stunning aquamarine of mirthful reflection that turns tempestuous when the climate calls for it. In Lotz’s photo, the tide is calm: Captivated, and with eyes as big as her headphones, Atkins considers the parts she sang for the string players on the sad ballad that states, in simple, certain terms, that drinking had consumed her life.

“I can see exactly where I was when I wrote that song,” she says of “Colors,” which she and Ellis had recorded in one take in the fitting gloom of a lightless studio. Atkins had just left New Jersey for Nashville with her tour manager husband, Ryan; she had been struggling with sobriety and had gone through a rough relapse when she found herself lonely in their new city and he told her he was heading out to work a two-month jaunt. On top of that, she’d hit a wall on the creative front, and the combination of unlucky breaks had her steeping in despondence. “I was writing tons of songs,” she says. “We were shopping around demos, because we had no money to make a record, and I just had no idea what we were gonna do, you know? It was just months and months of not getting any phone calls, at all, about songs that I thought were good, and a record I thought was, you know, cohesive.”

She decided to go to New York for a few days, as her old friends from college and frequent tour buddies, the Avett Brothers, invited her to their gig at Madison Square Garden, and Margo Price had encouraged her to come along for her Saturday Night Live performance that same weekend. “I just thought, ‘Dude, everybody has stuff to do except for me,’” she recalls. “I was like, ‘I’M QUITTING MUSIC.’ And then I drank a bottle of dark rum and called everyone I knew, and I was like, ‘I’m just gonna write a musical. Fuck this.’”

One of those calls was to Jim Sclavunos, drummer of the Bad Seeds, who stepped out from a photo shoot with Nick Cave to answer the phone and assure her that quitting simply wasn’t something she was “allowed” to do. Another was to Ryan. “I obviously had to tell my husband the next day that we couldn’t have booze in the house, and it was just freaking me out,” she says. The melody for “Colors” came later, when she was sad, tired, and singing lines of the song into her phone on a train platform on her way to the airport in Newark: “Everywhere I go, the only things I see are glowing brown and green. The bottle’s gonna kill me.” That’s when she set the backbone for Goodnight, Rhonda Lee, an album named for Atkins’s drunk alter-ego: This is her sober record, one that thrives off hard-won clarity throughout, but “Colors” is a breakthrough so simple, painful, and pure that it serves as the album’s anchor. It’s a reminder that the toughest trouble can teach us things, though its lessons — to pour out the poison; to wean off a person or substance you can’t quit — are difficult to learn or even discuss.

“I think there’s a lot of shame that comes with being a woman, and being a musician, and being an alcoholic,” she says. “There’s a lot of embarrassment to feel; it’s not pretty or cute to talk about. There are a lot of sober women in music, but I don’t know if a lot talk of them about it — the only one I can think of is Bonnie Raitt. I write about my life on every record. This was just what was going on, and I couldn’t really write about anything else. Being in and out of sobriety for two years was just totally taking over my life. It was all I could think about. It’s weird: You know when they’re like, ‘It gets better, it gets easier, and you’ll have a day when you don’t even think about booze.’ I couldn’t imagine that because, even in long stretches of sobriety, it was like, ‘I’ll just have one.’” She did get there — at Bonnaroo, where she didn’t even think about the open bar, of all places — and reaching that internal summit was illuminating. “I thought, ‘Now, I have all this room in my brain just to think of music and my husband when he comes home.’ It was such a good feeling, that I wasn’t constantly like, ‘I’m so fucked. How am I going to be unfucked?’”

Those “other things” flooding her grey matter include intricate arrangements and some of the most challenging compositions she’s written yet, as Goodnight, Rhonda Lee is as much an instrumental triumph as it is a lyrical one. In addition to Ellis and Sclavuno, Atkins sat down with a number of esteemed pals — including Chris Isaak and Binky Griptite of the Dap-Kings — to hone in on exactly what she wanted to sing and how she wanted to sing it. Thanks to these collaborations and the brassy guidance of Nile City Sound, the Fort Worth-based production team behind the timeless quality of Leon Bridges’s Coming Home, the result capitalizes on the wry grit of her New York-honed chops; her unadulterated adoration of Lee Hazelwood, Roy Orbison, and classic soul; and the alt-country framework that informed her first forays into songwriting. Though her marriage is wonderful and she’s open to compulsively unpacking her relationship with alcohol in songs like “Colors” and the album’s title track, Atkins found inspiration in painful memories of broken romance, the kind of stuff most people are eager to leave in the haze of a blackout-peppered past. One instance took the shape of “A Little Crazy,” the grand, lonely cowgirl call Atkins and Isaak wrote in an hour after he suggested that she revisit a relationship that went wrong instead of the one going right.

“He was like, ‘You’re happily married — but remember the guy you dated when we toured? Let’s write about that,’” she says. “A lot of [Goodnight, Rhonda Lee] was written about a past relationship. I wanted to own a lot of things instead of saying, ‘This is terrible and I’m a victim.’ After that one particular breakup, I was fucking nuts. I had no control of my emotions whatsoever. I was willing to degrade everything I believed in just to have that comfort back.”

And thus we have Goodnight, Rhonda Lee instead of Goodbye. By dusting off the conversations, opening heartwounds of the past, and keeping those tidal eyes of hers open, Atkins is able to mine the hurt, humiliation, and disappointment they caused for musical gold, just as she does while working through her sobriety with the tape rolling.

“There are aspects of Rhonda Lee that are still kind of there that I’m kind of grateful for. I didn’t get sober and become a giant square,” she laughs. “It’s more so being in a place where you feel confident and better about yourself, that you’re able to hold certain situations that were painful and have some empathy for the people involved in those situations — including yourself.”