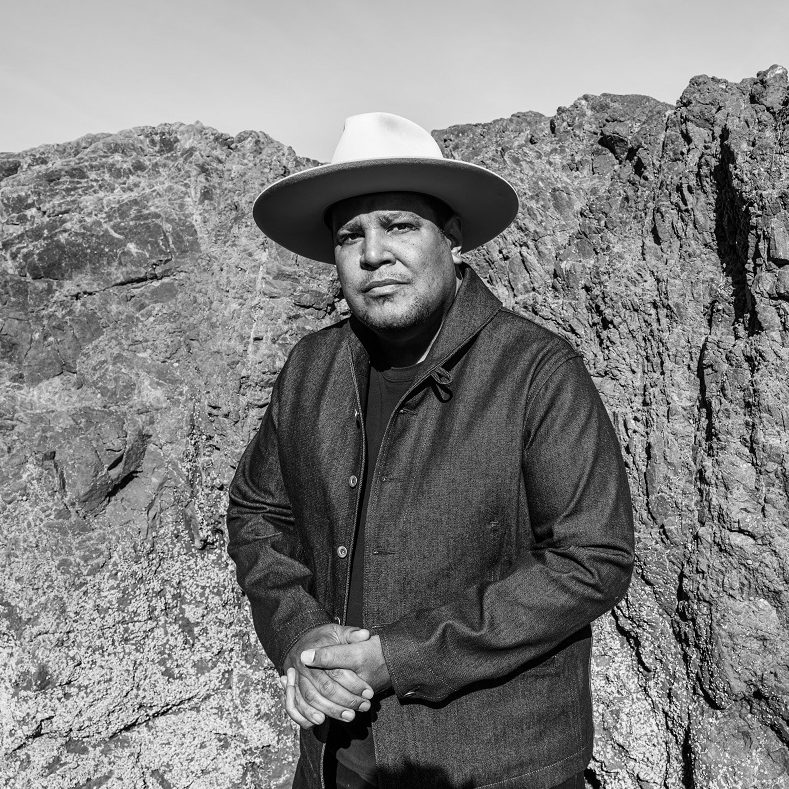

“I come to this project as a musicology outsider,” says Lukas Huffman, the writer and director of the short film, Night Music. As he became passionate about the field recordings made by John and Alan Lomax in the 1930s, a cinematic idea began to take shape. Wisely, Huffman sought guidance from an expert: Dom Flemons, also known as the American Songster.

As Flemons tells BGS, “Having spent the better part of twenty years performing and reimagining the songs collected by the Lomaxes in the field, I knew that I could help guide the film and curate the soundtrack accordingly.”

One of the most important and enduring bodies of work in the folk music realm, the Lomax field recordings have captured the imagination of listeners for generations and preserved countless voices and songs that would have otherwise been lost to history. However, by taking an unexpected approach to the script, Night Music allows longtime enthusiasts to approach the familiar narrative in a new way.

“We have chosen to tell a story that explores the racial tension inherent in the recording interactions,” Huffman explains. “From a contemporary perspective, considering the power inequality of these interactions helps to mature our understanding of music history. More importantly, focusing on the situation of the musician allows a deeper listening and feeling of the actual music on record. I’ve been surprised by how unsettling it is for audiences to experience this tension for themselves as we show the recreated scenes. The tension in the audience is palpable. This speaks to the power of cinema and the unresolved problems in the history of field recordings.”

After viewing Night Music below, read our BGS interview with Huffman and Flemons.

BGS: How did you first learn about John and Alan Lomax’s 1930s prison recordings?

Lukas Huffman: Around 2009, I stumbled on some of Alan’s Prison Songs CDs from the collection he recorded in Parchman Penitentiary. I found them in the Columbia University library when I was a student there. I did not have a CD player at the time and would sit in the library and listen. When I first heard the songs it was like a bolt of lightning. The hair on my neck stood up and they shot right through me. From there I went both back in time and forward in time through John and Alan Lomaxes discography.

Dom Flemons: I was first introduced to the work of John and Alan Lomax through the public library. When I first became interested in folk music, I made sure the early Library of Congress field recordings of Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie were staples within my collection. As I began to spend more time listening to the music of the 1960s folk revival, I found the name Alan Lomax mentioned again and again on any number of albums and publications. After a while, I decided to look up a few books on Alan Lomax and found not just one but many books written by the famed folklorist spanning from Mister Jelly Roll, his treatise on jazz pioneer Jelly Roll Morton to his later works on Cantometrics and Choreometrics. Alan believed that folk culture must be distributed on stage, on the air and in the classroom. In the 21st century, the need for folk culture to be portrayed as fair and accurately as possible on film is more necessary than ever. If it is not, it’s only a commercialized and watered down version of the real thing. Alan spent his whole career making sure the public had access to the “real thing,” as unfiltered and as human as the experiences that produced it.

I found the work of his father John A. Lomax to be much more challenging. One of the reasons for this was that John’s work was much more calculated and stoic in nature. While Alan’s work was based on the voice of his informant, John’s work was built on the composite literature of the anonymous “folk.” For Alan, the storyteller was always seen as a self-contained cultural librarian of sorts while John used the story teller as a means to get to the broader cultural message, a bigger communal story might convey. As a person who came of age in the 21st century, it was clear to me that both men were products of their time and their views on race, politics and social discourse were very different from my own. While I did not agree with everything they wrote or said about the music they collected, like most people, I could not deny the beauty of the music they documented for future generations.

David Patrick Kelly as musicologist John Lomax

What is it about those recordings that captivated you, and inspired you to make a film?

Huffman: Listening to the recording instantly transported me through time and into a place of tension. You can hear the humanity in the lyrics of the song, but even more so in the voices. I had (and still have) a visceral reaction to the music. Literally in my stomach and chest. As a filmmaker, when I get that feeling, I know there’s a creative potential to do something meaningful. That led me to researching the Lomaxes and ask, who are the guys making these recordings during this time — and what are their transactions like with the musicians? Within a small amount of research I knew there was a story here, which turned out to be an untold story.

I wrote a feature-length script set in 1933 that focuses on John and Alan’s first recording trip together. In real life that trip was a father-son road trip through the South. It was Alan’s first taste of life as a field recordist. John was already an established musicologist at this time, but it was his first time focusing on incarcerated African American musicians. These recordings would go on to be some of the most important music documentation of all time. The short film, Night Music, that is being released now is an excerpt from the feature. I took some scenes from the longer version and reworked them so they can tell a powerful, small story about the Lomaxes and their work.

Flemons: The first thing that drew me to these recordings was the hypnotic quality of the songs. As most song performances are made on a stage for the benefit of a paying audience, these performances were made by men singing for their own survival. As an African American person interested in the continuity of music in my own community, I could not help but think of the subversive nature of the lyrics which brings up a thin but poignant link to modern day hip-hop. These men are not rappers, but like rappers they are using pieces of the song tradition to create a platform for lyrical improvisation. Not unlike a musical “hook” as heard in most hip-hop songs, the polyphonic singing of the prison group sets the stage for the “lead” man to tell his tale of woes whether it is a story about himself, his relationship with his family or a woman, or a passive aggressive jab at the very prison guards no more than a few feet from him, standing at gunpoint.

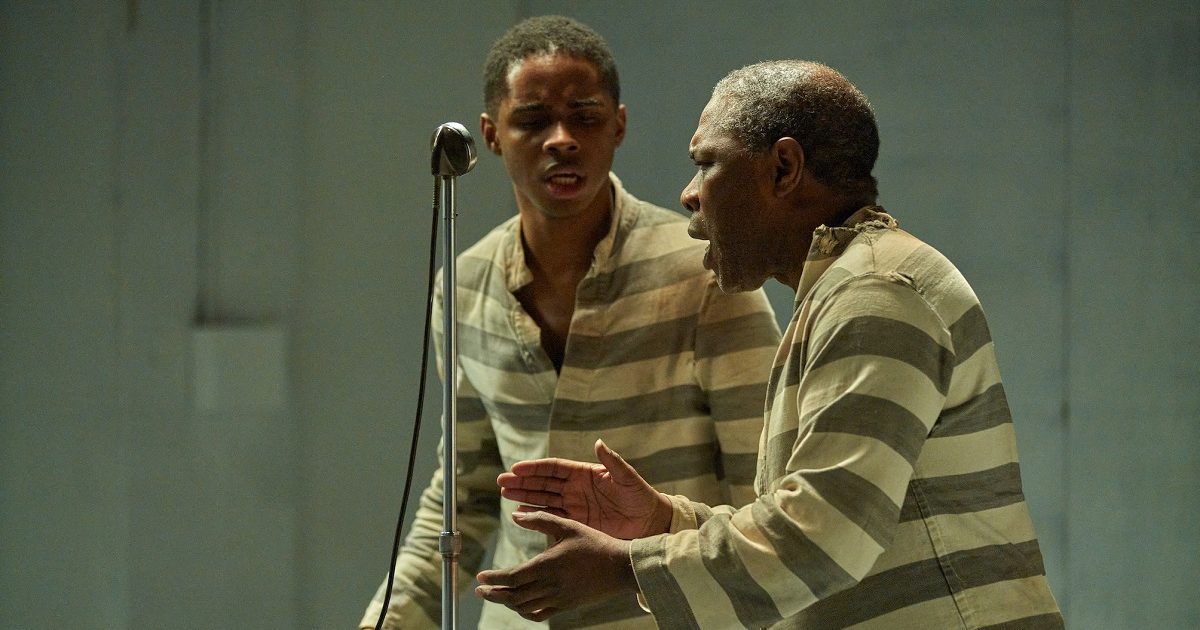

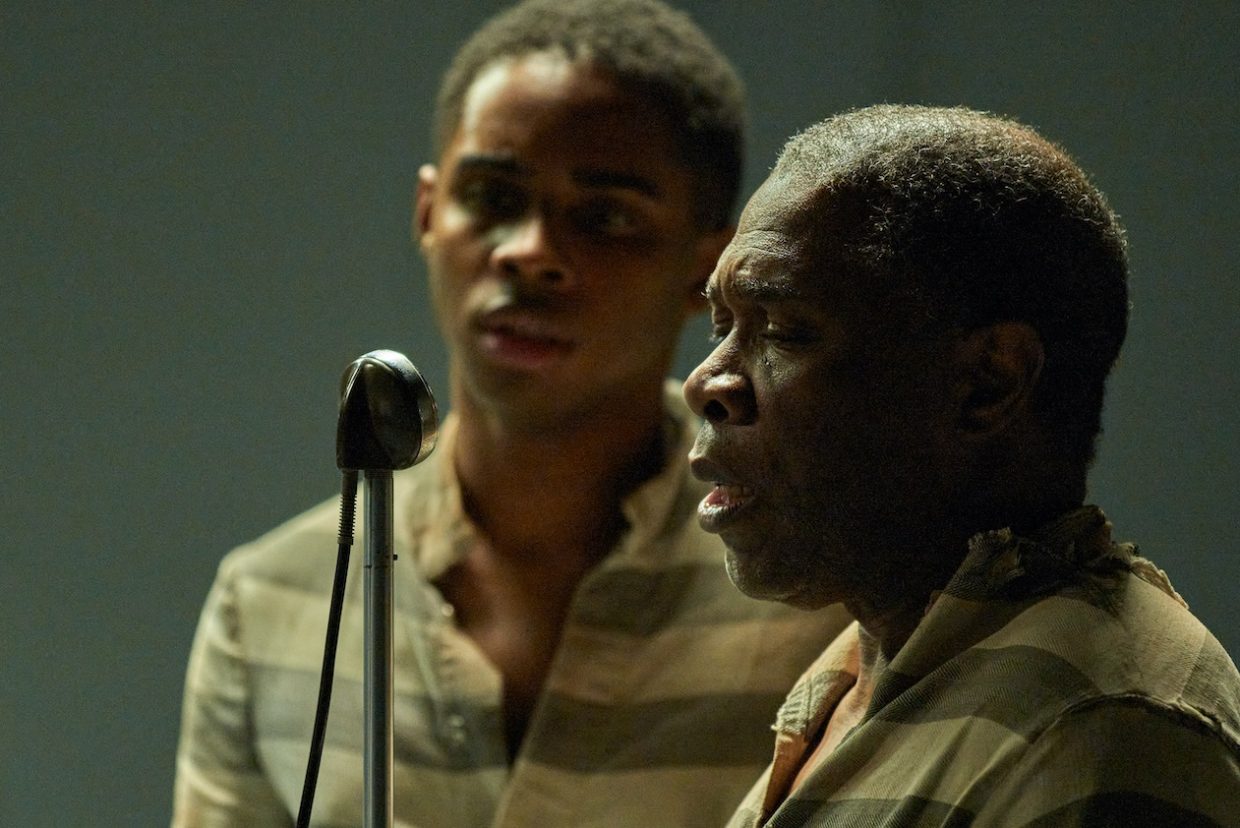

Manny Dunn as Walter Richardson, with Michael Potts as Father Dobie

Listening back to these recordings and understanding that the Lomaxes had limited supplies and resources to create this unique documentation made me see the brilliance of their work as folklorists. While in one way it is easy to question the intentions of the documentarians, it made me think of the world these unfortunate individuals experienced. No one cared about the songs they created for their own personal enjoyment. John and Alan Lomax, taking an anthropological approach to “Negro Folk Songs” captured performances that would have otherwise evaporated into thin air, never to be heard again. In a world dominated by three decades of strict segregation, the Lomaxes dared to say that the homegrown music of the African American community was just as important and “American” as the most high brow Euro-classical music of the day. They dared to present a style of music that could be documented for future generations paving the way for a much more informed and authentic “black folk music” aesthetic.

How did Dom Flemons get involved? What special qualities did he bring to the piece?

Huffman: I tracked down Dom because his musical career embodies the story of Night Music. He works to engage with the musical legacy of African American traditional and roots musicians. His perspective as a musician and Lomax scholar has been crucial in shaping the voices of the musicians in our story. There has been a lot of non-fiction storytelling around the Lomax legacy, which follows their perspective from experience to experience. I was interested in learning what the musicians in penitentiaries are feeling in the scenes before — and after — they record with the Lomaxes.

Dom understands, as much as anybody can, this perspective. He’s been instrumental in offering script feedback. In pre-production of the short film, Dom did singing rehearsals with Manny Dunn and Michael Potts, who play the prisoners. Dom gave some historical context about what the prisoners are bringing to their singing. Song was a form of spiritual communion, subversive resistance against the prison wardens, and emotional release. Each song has its own purpose in their daily life and there’s an emotional nuance for how it would have been vocalized. I think that getting these performance details right are so important if we want to help people reengage in an authentic way with the Lomax recordings.

David Patrick Kelly as musicologist John Lomax, pictured with Manny Dunn and Michael Potts.

Flemons: When I received my first message from Lukas Huffman, I was instantly drawn to his approach to the film. It is almost impossible to imagine what John and Alan Lomax experienced on the road during their early field recording sessions. It’s even harder to fathom the subtlety required to capture and document the songs of the forgotten. The environment was never ideal, the recording technology was temperamental and primitive and the discs which captured the audio were fragile and brittle.

When I began to work with actors Manny Dunn and Michael Potts, I wanted for them to understand the subtlety of the performers they were portraying and the context of their performances. The “subjects” are prisoners who have been pulled out of the fields where they are being worked like literal slaves. They do not know who these “men from the government” are and they do not have a full concept of why they would want to capture their music. Many had not even seen a recording machine before. Also the tension of racial violence and injustice is so mind-numbing these men have to appease both the folklorists and the prison guards while still retaining some sense of their own dignity. Their songs are their armor. Both actors as men of color understood that the situation was a precarious balancing act between taking pride in one’s own self and making the “boss” happy.

There are several perspectives to consider. In a situation where racial prejudice is one of the dominating features, there are expectations. The Lomaxes expect a song. The prisoners, hoping that their song goes back to Washington, expect freedom. The warden expects no trouble, from the Lomaxes or the prisoners before or after the recording session. All parties have very outlooks on life and the music being made. They all contributed to our national identity because the records are now a part of the Library of Congress in the American Folklife Center.

Luke Slattery as Alan Lomax, with David Patrick Kelly as John Lomax

What did you enjoy the most about creating this film?

Huffman: One of the reasons I’ve wanted to make the feature and short film is so that I can make it my job to be saturated in this music and surround myself with musicians. I have fallen in love with the John and Alan Lomax characters, so I enjoy being with them on their fictional character development. But, the unique pleasures of this film comes from listening to the music of these prisoners in the research and then experiencing the performers sing the traditional songs in real life, on set. When we were filming the singing sequences Manny and Michael knocked it out of the park. They did such justice to the power and beauty of the original pieces of music. When we’d do those takes everybody on set, cast and crew, would be drawn into the singing.

Flemons: What I have enjoyed the most about Night Music is that it is the first time the folkloric work of the Lomaxes has been given a full dramatic treatment. The musicians recorded by the Lomaxes were not professionals in the modern sense of the word. Alan Lomax always attested that the main purpose of he and his father’s early work was to empower disenfranchised people by giving them the means to hear themselves playing out of a loudspeaker. This single moment changed everything for these musicians who were now given a sense of pride and worth in their own songs in a world where no one would look twice at them or their music. Any number of musicians from Lead Belly, Muddy Waters to Pete Seeger were inspired by the Lomax’s recording machine and their recordings. The early prison recordings only emphasize this dynamic even more so as the prisoners documented in these acetate discs would never hear nor see the legacy that their contributions left behind. It is our job as the makers of this film to make sure that Night Music is a combination of brilliant music and a revealing portrayal of the people and the moments that created it.

Photo Credit: Clay Rodriguez

Festival Screenings and Awards

Breckenridge Film Festival, CO – Winner, Best Short Narrative & Best Editing

SCAD Savannah Film Festival, GA

Lake Country Film Festival, IL

SFIndie Fest Decibels Film Festival, CA

Cinema on the Bayou, LA

Made Here Film Festival, VT

Cast & Crew Credits

Written & Directed by: Lukas Huffman

Starring: David Patrick Kelly, Michael Potts, Kevin Breznahan, Luke Slattery, Manny Dunn

Produced by: Anthony Santos

Casting Director: Kate Geller

Musical Director: Dom Flemons

Director of Photography: Michael Belcher

Production Designer: Ambika Subra

Editor: Lukas Huffman

Composer: Ryder McNair

Colorist: Alexia Salingaros

Finishing Services: Ancillary Post

Executive Producer: Huffman Studio, Inc.