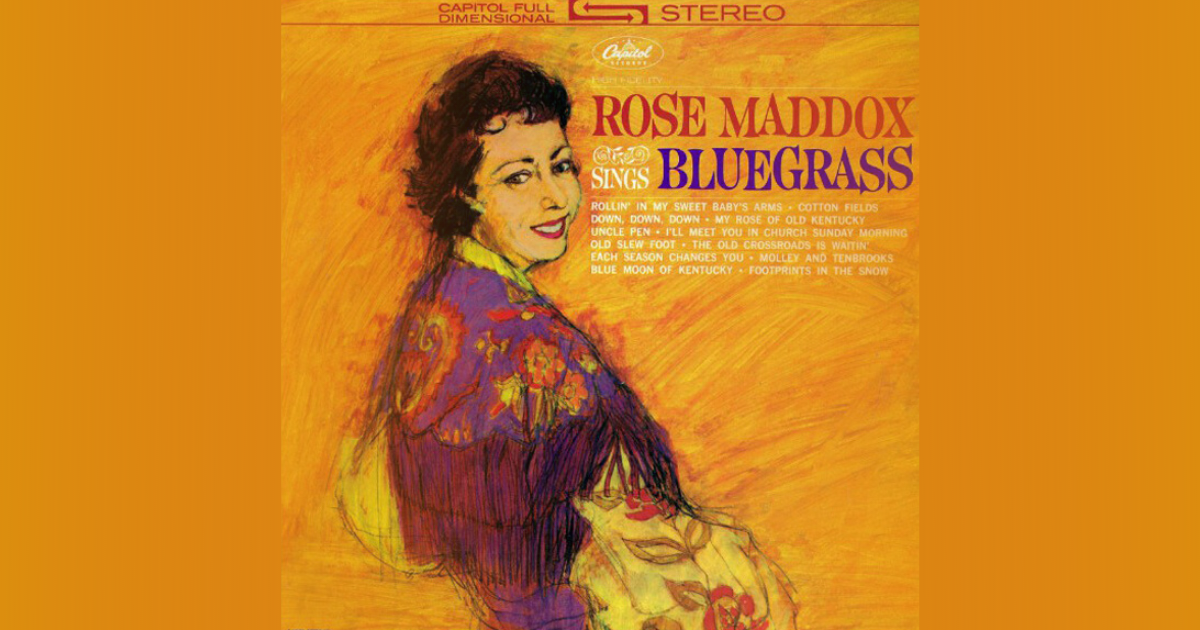

Rose Maddox, the lead singer of the Most Colorful Hillbilly Band in America, made a significant mark in bluegrass, too, as the first woman ever to record a bluegrass album. Her incredible rags to-riches story touches on boxcars and sharecropping, the Grand Ole Opry and Buck Owens, and finally the Father of Bluegrass Music himself, Bill Monroe, who laid the foundation for that seminal 1962 Capitol Records LP, Rose Maddox Sings Bluegrass.

Born on August 15, 1925, in Boaz, Alabama, Roselea Arbana Maddox arrived in a family with some musical heritage. Her paternal grandfather was a fiddler and roaming preacher, while her uncle Foncey gave lessons to locals and performed in blackface. Rose’s father, Charlie Maddox, worked as a sharecropper and hired hand. After getting stiffed for a job chopping wood, Charlie decided to skip town and finally indulge his wife Lula’s lifelong dream of living in California, panning for gold. They sold everything they had and stashed away the proceeds — just $35. The two oldest children stayed behind, while the youngest five and their parents set out for the Golden State in the spring of 1933.

How? On foot. Then hitchhiking. And after crossing over the state line to Mississippi and encountering another family who explained train-hopping, the seven Maddoxes rode the boxcars all the way west. Rose was 7 years old. They settled and resettled in various towns, with their situation once so dire that Lula had to place Rose with another family — but Rose acted up so often that the family gave her back. When Charlie got harvesting work in Modesto, the family followed and became what they called “fruit tramps.”

With some stability, the kids were putting down roots in Modesto. They collected whiskey bottles, turned them in for a penny a piece, then spent their dimes on movies. One Sunday the Sons of the Pioneers appeared in person at the Strand Theater. At that moment, Rose had found her calling — to be a singer. Her brother Fred had a similar epiphany while picking cotton that fall. After hearing that the band who’d just played the rodeo made $100, he decided it was time to get into the music business. Acting as manager, he found a furniture store to sponsor some radio spots. The caveat was simple: The furniture store owner wanted a girl singer. Thus, the Maddox Brothers & Rose were launched — with the spunky lead vocalist just 11 years old.

They followed the California rodeo circuit and played bars for tips, then won a State Fair competition that crowned them California’s best hillbilly band. However, things unraveled for a time in the early 1940s, as Fred, Don, and Cal were drafted in World War I, and Rose became an unhappy bride at 16, then a single mother at 18. Auditions with Roy Acuff and Bob Wills went nowhere. She played occasional gigs with other bands until the war ended and the Maddox Brothers & Rose reformed, with the youngest Maddox child, Henry, now joining on mandolin.

Playing dances as well as radio shows, the group shifted their sound to get people moving. Their look got an overhaul after Roy Rogers recommended Los Angeles tailor Nathan Turk, a pioneer of flashy Western stagewear. They also signed a deal with 4 Star Records, an indie label that marketed them as Most Colorful Hillbilly Band in America. Their repertoire ranged from Woody Guthrie’s “Philadelphia Lawyer” to Hank Williams’ “Honky Tonkin'” to the gospel tune “Gathering Flowers for the Master’s Bouquet.” They made their Opry debut in 1949, where they met Bill Monroe, and became the first hillbilly band the play the Las Vegas Strip. That same year, however, Charlie and Lula Maddox divorced.

By 1950, various members of the family were living in Hollywood. A beautiful woman of 25, Rose took courses in modeling and vocal control, although Lula would not allow her to date. The band appeared on broadcasts like Hometown Jamboree and Town and Country in Southern California, as well as the regional show, the Louisiana Hayride. Columbia Records signed her as a solo act in 1953. With rock ‘n’ roll in full force in 1956, the Maddox Brothers & Rose sputtered, then disbanded, and not without some bitterness as Rose’s career still flourished. The Opry didn’t appreciate her first solo appearance though, when she wore a blue satin skirt that exposed her bare midriff. Nonetheless she relocated to Nashville (with the ever-vigilant Lula) and became an Opry member in 1956, but quit about six months later when Roy Acuff complained she (and not other Opry members who were touring) made appearances on too many local TV shows.

That professional setback might have given the perception that Rose couldn’t have a career without her brothers. That proved quite untrue. Hometown Jamboree in Los Angeles hired her, which led to plenty of gigs. When the Columbia deal ended, she recorded for two independent labels before signing with Capitol Records in 1959. When Lula tried to boss around producer Ken Nelson, he banned her from all future sessions. Rose, by this time 33 years old and still under her mother’s thumb, was secretly delighted. Taking things a step further, Rose eloped with a nightclub owner that December, then embarked on a European tour.

For Capitol, she made her first Billboard chart appearance ever with the honky-tonk weeper “Gambler’s Love,” climbing to No. 22 in 1959. Her first solo album, The One Rose, dropped in 1960, followed by a gospel set titled Glorybound Train. By 1961, she took “Kissing My Pillow” and “I Want to Live Again” to No. 14 and No. 15, respectively. Johnny Cash invited her to join his road show and Buck Owens asked to record some duets. Those twangy tracks, “Loose Talk” and “Mental Cruelty,” both entered the Top 10 in 1961. Her third album for Capitol, A Big Bouquet of Roses, appeared later that year.

The year 1962 proved to be the pinnacle of her career, as Bill Monroe encouraged her to make a bluegrass album. Because they recorded for competing labels, Big Mon anonymously played on the first day of the two-day session, recording several numbers from his own repertoire. Donna Stoneman stepped in on mandolin on the second day with the remainder of the material. Reno & Smiley joined the session too. Monroe later told Maddox biographer Jonny Whiteside, “The Maddox Brothers & Rose always had their own style, but you must remember their home was Alabama, and I always thought they sang a lot of the old Southern style of singin’. So I enjoyed helpin’ her on one of her albums. She had some great entertainers workin’ on it, and it didn’t take long at all.”

Maddox herself explained, “Bill Monroe has always told me that I sang bluegrass, and to me what he was talkin’ about is just what I call ‘hillbilly.'” She may not have agreed with the terminology, but she certainly adhered to the enthusiasm of the best bluegrass singers. Rose Maddox Sings Bluegrass became the first bluegrass LP recorded by a woman. Its release coincided with the chart success of an earlier country single, “Sing a Little Song of Heartache,” which rose to No. 3 (and practically begs for a bluegrass remake).

Without Lula to intervene, Rose’s life on the road nearly derailed her, with infidelity, volatility toward band members, and a propensity for Benzedrene wrecking her marriage and her professional reputation. A heavy schedule of international touring wreaked havoc on her voice, too. The singles she did release were moody, if not morbid. Although she eclipsed Patsy Cline and Kitty Wells to be named Cashbox‘s female country artist of 1963, her chart momentum fizzled out after her final album with Capitol, 1963’s Alone With You. Still she continued to tour with Buck Owens and Merle Haggard, with her grown son Donnie as her sideman.

Maddox occasionally recorded for small labels in the ’70s and ’80s to modest results, while her venues now included the San Francisco gay bars that embraced the Urban Cowboy phenomenon, as well as the annual gay rodeo in Reno, Nevada. She performed with the Vern Williams Band in folk clubs, too, and recorded a 1984 album with Merle Haggard & the Strangers that was funded by fans. A number of Arhoolie Records reissues helped keep her loyal audience appeased, while introducing her vivacious music to a new generation. She and her brother Fred patched things up for a 50th anniversary celebration of the Maddox Brothers & Rose in Delano, California.

Too often overlooked among the country performers of her era, Maddox landed her first Grammy nomination for her 1994 Arhoolie release, $35 and a Dream, in the category of Best Bluegrass Album. She recounted her exceptional career in the 1997 biography, Ramblin’ Rose: The Life and Career of Rose Maddox, and died the following year at age 71 in Ashland, Oregon. Remarkably, her life story has not been adapted for Hollywood, nor has she been inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame or the Bluegrass Hall of Fame. Yet her catalog still shines as a beacon for listeners who seek out traditional music with an undeniable West Coast flair.

On the final track of that final album, Johnny Cash intones, “I worked with Rose Maddox a lot back over the years. And I found that when she started working my show that she was probably the most fascinating, exciting performer that I’d ever seen in my life. She was a total performer. She captivated the audience. She held them in the palm of her hand and made ‘em do whatever she wanted to. The songs that she sang were classics, and I loved the way she sang and kind of danced at the same time. I thought there was, and still think that, there will never be a woman who could outperform Rose Maddox. She’s an American classic.”