Most of singer Magos Herrera’s new album, a collaboration with the string quartet Brooklyn Rider, draws on words and music written decades ago by Latin American poets and composers who spoke out against oppression, at the risk of their freedom and, in some cases, their lives. These are complemented by the haunting folk song “La Llarona,” already a staple of the Mexican canon but now globally known via its prominent place in the animated movie Coco.

Composer-saxophonist Miguel Zenón’s new work also teams him with a string ensemble, Chicago’s Spektral Quartet. The collection taps centuries of traditions, both musical and cultural, from his native Puerto Rico, to some extent to shine a light on the historic ignorance of many in the United States for its vibrant commonwealth. Folk melodies, evocations of religious festivals, and impressions of rural villages all mix in a celebration of that legacy.

But each is also very much of the moment, in the moment, tied to circumstances of the here and now, pointedly so. This is music with immediacy, with a purpose.

“I think these days we don’t have the luxury not to have a purpose,” says Herrera. The title of her album gives that purpose shape: Dreamers.

“It’s the spirit of our times, at least to me, after some time of confusion, showing how we got into these times, not only for what happens in America but in the world,” she says. “It was in invitation to ground in the reason why we make music and the purpose of our artistry and our music. And also because one of the first reasons I moved to New York 11 years ago was for all the opposite virtues of what we see — democracy, conversation, interaction, etc. The long story short is [the album] is really a response to what happens to the spirit of our times, beyond complaining.”

She’s made a career of exploring both her own and the larger Latin American heritage, primarily in a jazz context, but this album is very personal.

“I’m a Mexican in Trump America,” she says. “So this conversation of my situation as an immigrant, in every sense I thought it was a beautiful reaffirmation of my background to celebrate these incredibly huge masters of the word.” These influential poets and composers include Mexican poet Octavio Paz, Spanish martyr Frederico Garcia Lorca, Chilean “Nueva Canción” activist Violetta Parra, amd jailed and exiled Brazilians Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil and João Gilberto.

Herrera adds, “They lived in dark times, but changed the conversation, and keep inspiring us with what they wrote. It’s music of the incredible poets, some effected by the regimes in different ways, some were exiled, Lorca was murdered. So to honor them, celebrate their love for humanity, for democracy and the love for imagination of their world.”

Zenón’s album Yo Soy La Tradición is not as explicitly political, though he says it’s hard not to find that in the series of eight new compositions, his alto sax woven with the Spektral strings.

Zenón says that much of the mission of this album is to shed a light on the beleaguered island commonwealth of Puerto Rico – not just post-Maria, with help still slow to come, but with a mind on issues that have existed for decades, some coming from its perceived status as a “lesser” part of the U.S. But the learning process most essential to the album, he says, was his own.

“As a Puerto Rican and a Puerto Rican musician, I’m amazed by how little I know,” he says. “Always something to discover, something around the corner. And when you get into something, there’s something more after that. A lot of the ideas on the album I’ve been focused on for a while, but wanted to dig deeper for this project.”

For each piece in the set commissioned by Chicago’s Hyde Park Jazz Festival he took some aspect of Puerto Rican life — a folk tune, a religious ritual, a community celebration — and fashioned a vibrant fantasia. “Rosario” is inspired by “El Rosario Cantado,” a version of the Holy Rosary passed down through the generations traditionally played on folk instruments at funerals and other occasions. “Yumac” is inspired by a musical form from the town of Camuy (the title is that spelled backwards) with an unusual cadence and rhyming scheme. And with “Promesa” he portrays the annual celebration on the eve of the Jan. 6 saints’ day honoring the Three Kings who took gifts to Jesus in the manger.

“The Promesa, that tradition is so unique and so special, so amazing,” he says. “People make a promise to a specific deity, usually Catholic, like the Virgin. I wrote this piece for the Three Kings. In Puerto Rico and Latin America, the Three Kings’ day is bigger than Christmas and is celebrated on Jan. 6 every year. You get your gifts then.”

For these saints’ day celebrations, people honor promises made to the heavenly figures who they asked for help with health or financial troubles or other matters, usually with a big party the night before. El Día de Reyes, this day, is the most elaborate.

“It involves songs and an offering and the music is very specific, which spoke to me,” he says. “There are bands that all they do is play the Promesa events, they have the repertoire. All the songs are about the Kings.”

One song in particular caught his imagination, a seven-bar piece (unusual for a folk song, he notes) and expanded on that, as well as on another song, “Les Tres Marias,” both in diatonic scales, which he said gave him a lot of room to work harmonically, which he does in what proves a vibrant intersection of folk, jazz and modern classical approaches.

And that is something else the two albums have in common. Each takes various aspects of those elements to create their own distinctive form of chamber music. Zenón’s is spare but lively in its evocativeness. The Herrera/Rider project has a larger sonic landscape, in part simply from featuring her vocals, but also through bringing in percussionists and other musicians to expand the range. For Herrera, like Zenón, the most profound revelations in the course of her project were personal, insights into her own heritage in the context of Latin American culture.

“It was more a reconnection to my origins, what I was listening to growing up,” she says.

But she also relished the chance to delve into everything from Brazilian bossa and tropicalia to flamenco to Mexican folk, all given exciting twists by Brooklyn Rider and a complement of arrangers including the quartet’s Colin Jacobson, Argentine musician Guillermo Klein and Venezuela-born Gonzalo Grau, who also plays percussion on the album. As well, she stepped up to the challenge of composing new music for three songs, including “Niña” and “Dreams” using words by Paz. In that she took inspiration and energy not just from older sounds, but also from new movements.

“There is a very interesting new wave of Argentine instrumental music,” she says. “It connects with the Brazilian instrumental scene. The song ‘Milonga Gris’ by Carlos Aguirre, a wordless song, that’s from that.”

The final two songs on the album make the connections very strongly, of musical styles and of the resonance of themes from the past with today. “La Llorona” tells of a woman’s ghost, searching for her lost children, ties now to the recent reports of families separated by U.S. immigration authorities. Pointedly, on the album it’s followed by the closing “Undio,” a 1973 João Gilberto bossa nova that had been part of the Brooklyn Rider repertoire before meeting Herrera. The song, in Jacobsen’s arrangement, starts with a ghostly cluster of strings before revealing a somber, yet hopeful, sense of uncertainty.

Johnny Gandelsman, Brooklyn Rider violinist and producer of Dreamers, also feels a connection to the material, having his origins in an authoritarian state, before moving with his family to Israel at 12 and then to the U.S. at 17. The material on Dreamers and the writers’ experiences behind it resonate with him deeply, even more in what he sees in the current political climate. “La Llorona” took on even greater personal meaning when he took his young daughter to daycare and heard another girl, who knew it through Coco, asking what the lyrics meant. He hopes that the new album presents a sense of optimism.

“In the world, America has been a beacon of hope for so many people who have struggled in their own countries,” he says. “I guess we just want to say that it’s still a place that can provide shelter and hope and opportunity for people, and we want to see the beauty in it.”

Color photo of Magos Herrera & Brooklyn Rider by Shervin Lainez

Black-and-white photo of Magos Herrera & Brooklyn Rider by Ryan Nava

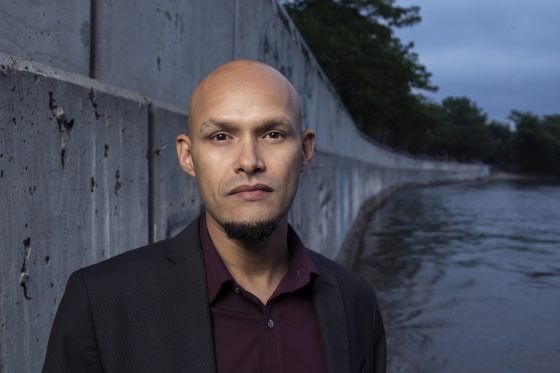

Photo of Miguel Zenón by Jimmy Katz