The motivation for Phil Cook’s unapologetically familiar gospel sound is simple: he LOVES that style of music and the people he’s learned it from. At times he veers into Appalachian instrumentation, reflecting his current North Carolina surroundings, and there’s individuality and innovation aplenty. But this Wisconsin kid and his band never stray far from a black gospel blueprint, incorporating backing choirs, tinkling piano stabs, organ that’s more Booker T. than Benmont T., and a vocal delivery that’s loose and expressive.

On his new album, People Are My Drug, Cook invites us to marvel gratefully and joyfully at the greatness of so many people whose creativity and communal originality have flourished under oppression, as well as those who hold the weight of the world within their silence.

There is a definite space that People Are My Drug lives in. I’d love to hear your thoughts on that.

I’m lucky. If I’ve learned anything, it’s to surround yourself with people that know what they’re doing, have a lot of experience, and have something to say. I can possess those things, not all at the same damn time, but if I’m surrounded by other people, I feel safer to be that multiplicity. So my circle starts with my brother, as a producer who knows me better than any other and helps me deliver the most honest statement that I can make. He knows when I’m hiding and helps me stand up tall and be who I have to be to do the thing.

From there, all the musicians in the band – we essentially made the record in two days. Most everything was made in a studio in Wisconsin, which happens to be owned and operated by my old friend Justin Vernon. So we brought the whole crew up, and we holed up in a live room, the four of us – drums, bass, keys, and me. We played for two straight days and didn’t leave the room. We trusted the people across the house were doing their job.

And that’s where this record starts: trust. I am surrounded by musicians that I trust more than anyone else in that moment on stage or in the studio, and we made that a bubble. Then after we were done we had a nice dinner and went into the control room and listened to the record that we’d just made. We were laughing and smiling at each other. There are little moments that happen all over the place. We start out “He Gives Us All His Love,” and I was like, “Bass, I love ya.” And when we listened back to it, that’s exactly what the vibe of the entire record is, that fraternal kind of vibe.

Speaking of fraternity, “He Gives Us All His Love” stirs me to feel universally connected to humankind, more brotherhood of man than fatherhood of God. Is that what you were going for?

Yeah! It’s my favorite Randy Newman song off of Sail Away because it’s the one time he lets his sardonic humor-guard down for a very simple song about gratefulness and generosity, and I like that a lot. Funny story, we sang our version of that song for the first time and halfway through it a woman in the front row looks up at me with a little smile and goes, “How do you know it’s a ‘he’?” and immediately switched the entire perspective of the song. And the rest of the song we sang “She gives us all her love.” I was like, “Well, this is how we’re gonna perform it from now on!”

And that’s the kind of spontaneous moment that you have to pay attention to as a musician, to be open when something passes by and be like, “That’s it! Cool! Switch directions. Let’s hit this.” And you trust. It made for a really beautiful moment at a hometown show. So yeah, I do feel that the fraternity, the brotherhood of man, is the heart and soul of how gospel music plays a role in my life. It’s much more of a family, a community. That’s the togetherness of space that I think the center of this record is.

What I ultimately got out of a childhood in church was this great community that was really supportive of me being who I was. They saw a little kid with glasses in Wisconsin, and they told me to keep being who I want to be. That’s what every kid deserves. And as much as I walked away from church, when something is a part of you in your childhood, you can’t just walk away from it. It’s going to be a part of you for the rest of your life, even if you don’t have a weekly interaction with it.

And I think gospel music in general has been a part of me having this continual, ongoing dialogue with my faith and my questions in a deeper way that feels really real, that feels like a real practice, nothing about dogma, nothing about a system. It’s not gonna work for everybody, but I was able to dial back my anxiety medication after two or three years pretty much listening to quartet black gospel music and getting into it until I started to feel it.

What is it about gospel music that connects you to that human moment?

Well, gospel music is the original garden of all music that comes out of America. On one side you’ve got the blues, which way more people in the white community are familiar with. That’s ubiquitous. A lot of people know who Robert Johnson is, Buddy Guy, B.B. King, even someone more eclipsing, like Jimi Hendrix. A lot of those artists were torn their whole lives between what they were doing for money and what they were doing on Sunday morning.

Religion never left them either. Religion gave them so much. So even blues artists weren’t free of that spiritual paradox. If you look at some of the greatest singers, they all came out of this garden of the church. Aretha, Curtis Mayfield, Sam Cooke, all the Staples Singers – a vast number that were able to have a safe space as they were growing up. The safest space they could find was church, the place where they were able to seed and plant their art and their voice.

The church was also the source of this friendly competition with players raised up there. You’ve got young kids in the wings watching every single move that you’re doing, and they’re going home and practicing. It creates a whole circle of virtuosity and innovation. It was the only place for it to thrive, and, damnit, it thrived. It changed the entire world. Most of those artists went on to big careers in soul music and left the church in some ways. The church didn’t leave them though. That was with them the entire way.

I appreciate the way in this album you direct attention toward others and away from yourself. I’ve cried twice this morning listening to “Another Mother’s Son.”

It’s heavy. I had my own experience with almost losing my youngest son when he was born to some complications with respiratory stuff. You get close to almost losing the thing that you hold most precious, even though you just met him. Your family is forced to grip with the possibility that things aren’t gonna turn out ok. I don’t know who isn’t gonna be affected by a situation like that in a way that’s gonna crack your heart wide open. And what happens after that is really important.

He came home from the hospital and I put him to bed; we’d had an incredible family day. I felt like, “Oh, my family is so strong. I’m so thankful for this family. We’re gonna get through this life together and it’s gonna be ok.” And then I checked Instagram and saw the video that Philando Castile’s girlfriend, Diamond, took of the police officer after [the officer] shot him multiple times with her daughter in the back seat of the car. In that moment it was the juxtaposition of how safe I was feeling, how strong my family felt, to seeing a young man who was such a giving soul ripped so violently from his own mother, who called him her miracle child.

She wasn’t supposed to be able to have kids and she had a son, Philando Castile. And then this broken-ass justice system completely stole him away from her and everyone else that loved him. And it just hit me way harder than it normally would have because of what I went through. Often times you go through something and then maybe days, months, years down the line, something else will happen that will give you a whole new perspective on what you experienced initially.

The second fold was one of my bandmates, a phenomenally gifted musician and gregarious, incredible human being, Brevan [Hampden], who came over one night to meet [my son] Amos. Brevan was raised by his mother, who had three boys, all black men in America growing up. We sat on the porch drinking beers, and the talk turned to all this stuff. I love Brevan with all my heart. We’ve gone through a lot in our lives as musicians together in just a few years. And I think that moment just a few days after Philando Castile’s death really delivered home the two worlds that are so separate in this country. What some mothers don’t have to worry about. And what some mothers have to live in fear of every single day. And no matter how hard they sandbag and prepare against the terrible reality that could happen, their black son is walking out the door every day with a target on his chest. There’s no guarantees.

Brevan was raised sternly about how to interact with police, body language, tone of voice, every single thing. It was so foreign to me to listen to that, growing up in northern Wisconsin, the diversity-free capitol of the world. I knew all the police officers in Chippewa Falls. They all knew my mom and dad. I don’t know how many benefits of a doubt I got because of that. I can’t ignore that. I’m gonna go through the rest of my life grateful that it’s never happened to me. It’s a poisonous system, and I moved south to get away from indifference, so I could be in more of an interactive dialogue with communities that didn’t look, think, and act like me.

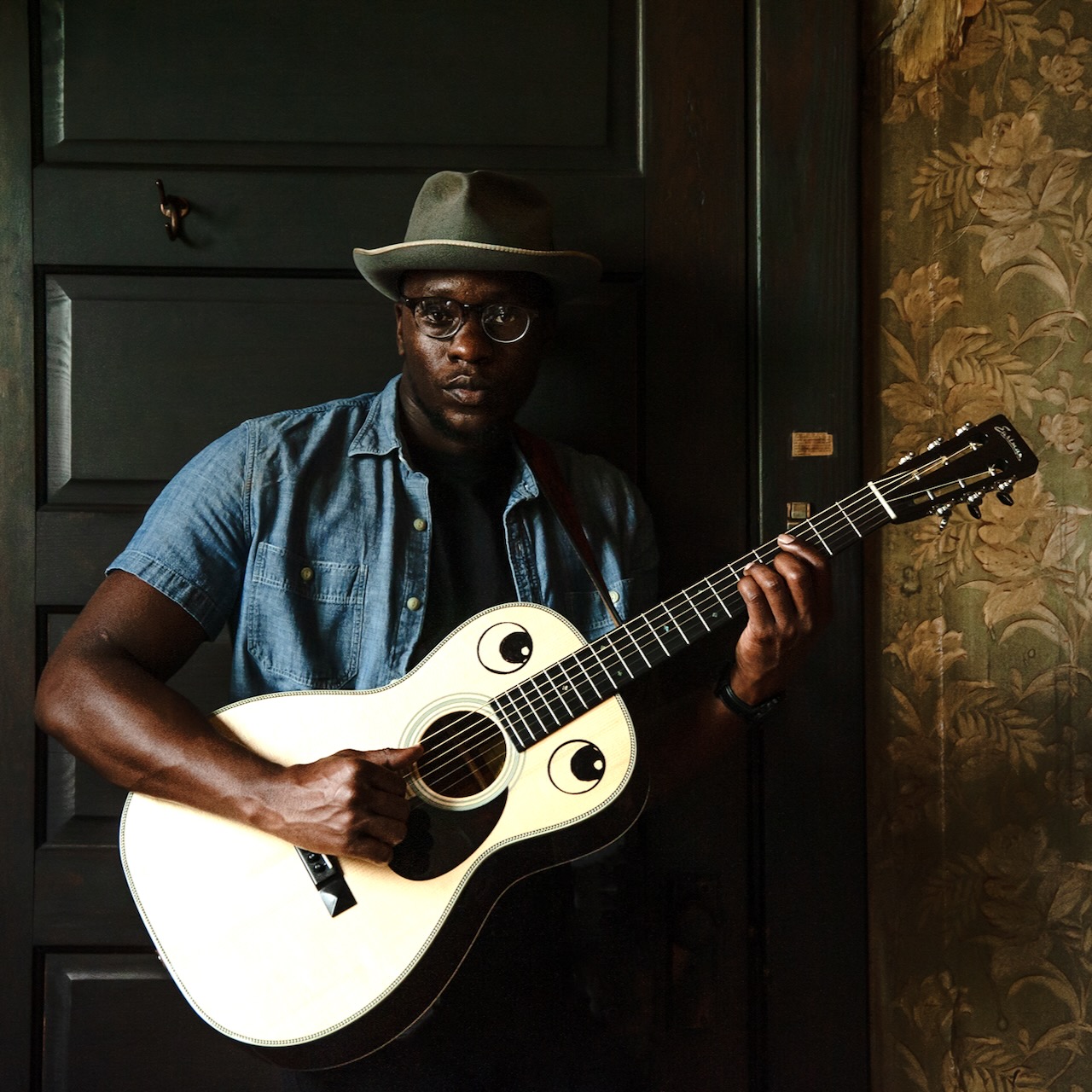

Photo credit: Josh Wool (Top); Graham Tolbert (Middle)