It was a crisp fall day in Memphis, late October or early November 1909, when W.C. Handy loaded seven musicians onto a wagon and rode it to into the heart of the city’s business district. There, they launched into a lively piece of music he had adapted using elements picked from street musicians and gambling den entertainers, the newly penned lyrics stumping for mayoral candidate Edward Hull Crump.

Mr. Crump won’t ‘low no easy riders here

We don’t care what Mr. Crump don’t ‘low

We gon’ to bar’l-house anyhow

As Preston Lauterbach describes the scene in his fascinating new book, Beale Street Dynasty: Sex, Song, and the Struggle for the Soul of Memphis, it was a fairly raucous performance, especially for downtown Memphis. “As the song swung to life, [Handy] saw bosses twirling their stenographers in the windows above. Colored dancers swayed on the sidewalk.” The performance marks the first time blues music had been played for a public audience, the first time it crawled off of Beale and commanded the attention of the general public — or, to put it bluntly, white people.

Handy’s “true claim to fame was never to have invented blues music outright, but to have crossed the music over from Beale Street to Main Street, from colored honky-tonks to mainstream America,” Lauterbach writes, adding that the musician “had carried this Negro music to where it could be widely influential and historically recognized.”

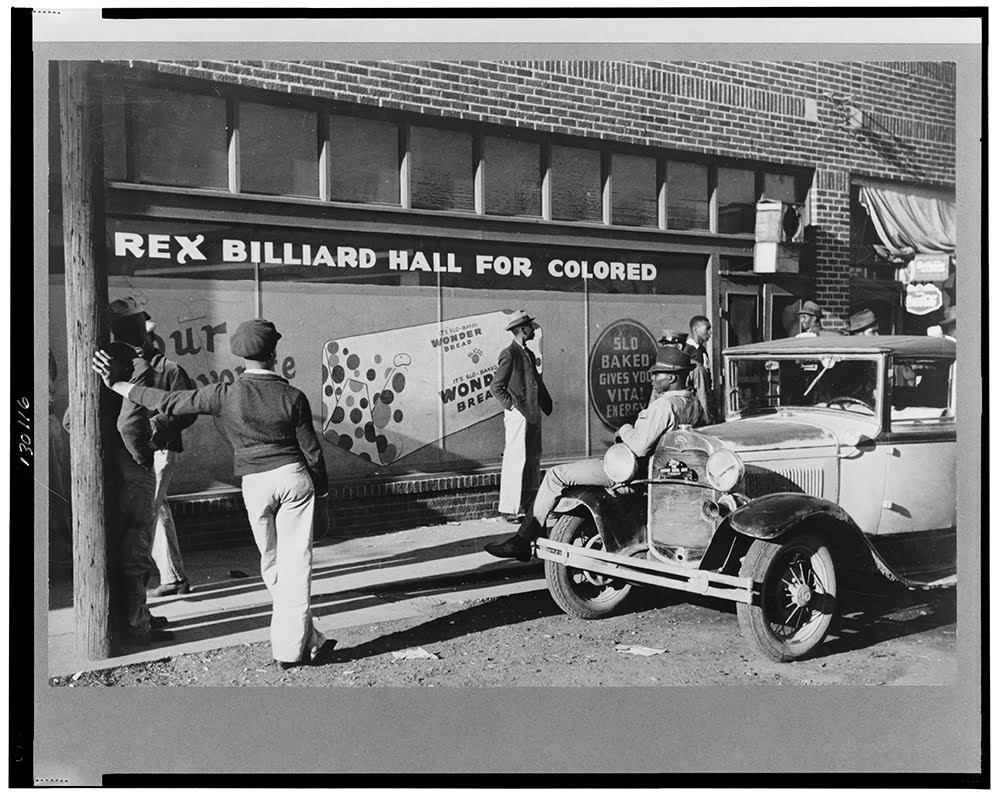

None of the musicians on the wagon, nor any of the bosses dipping their secretaries, nor anyone within earshot would have understood the significance of the event, yet it might be considered the big bang of American popular music, as well as a turning point in local history. In Beale Street Dynasty, Lauterbach recounts the history of the neighborhood, its various rises and falls over more than a century. “What made Beale so unique was that there wasn’t another place like it in the 1800s,” says Lauterbach. “It was the Main Street of black America, the hub of Southern black culture. It was Harlem 40 years before the Harlem Renaissance.”

He portrays these events — the race riots, the political corruption, the musical innovation, the social striving — through the eyes of Robert Church, America’s first black millionaire and a dynamic character in Memphis history. “He had been born a slave,” says Lauterbach, “but he managed to build his fortune — first on saloons and gambling halls, then on brothels. He created this underworld empire, but funneled a lot of the proceeds into legitimate businesses and more progressive organizations. He was using vice to underwrite virtue.”

Of course, Beale Street had an amazing soundtrack, with musicians like fiddler Jim Turner and W.C. Handy playing in establishments up and down Beale and nearby Gayoso. Music was, for many years, only secondary to the business and political machinations, but “that’s reversed now,” says Lauterbach. “Now the way the story is portrayed, the music overshadows the power. The music is really what most people think of when they think of Beale Street.”

More than a century after Handy’s public debut, few non-musical remnants of the era remain, save for a few old buildings and some parks that bear names like Crump and Snowden. Much like the rest of downtown Memphis, Beale suffered during the mid- and late-20th century, when white flight left downtown all but empty. The neighborhood decayed, its buildings left to rot and collapse.”

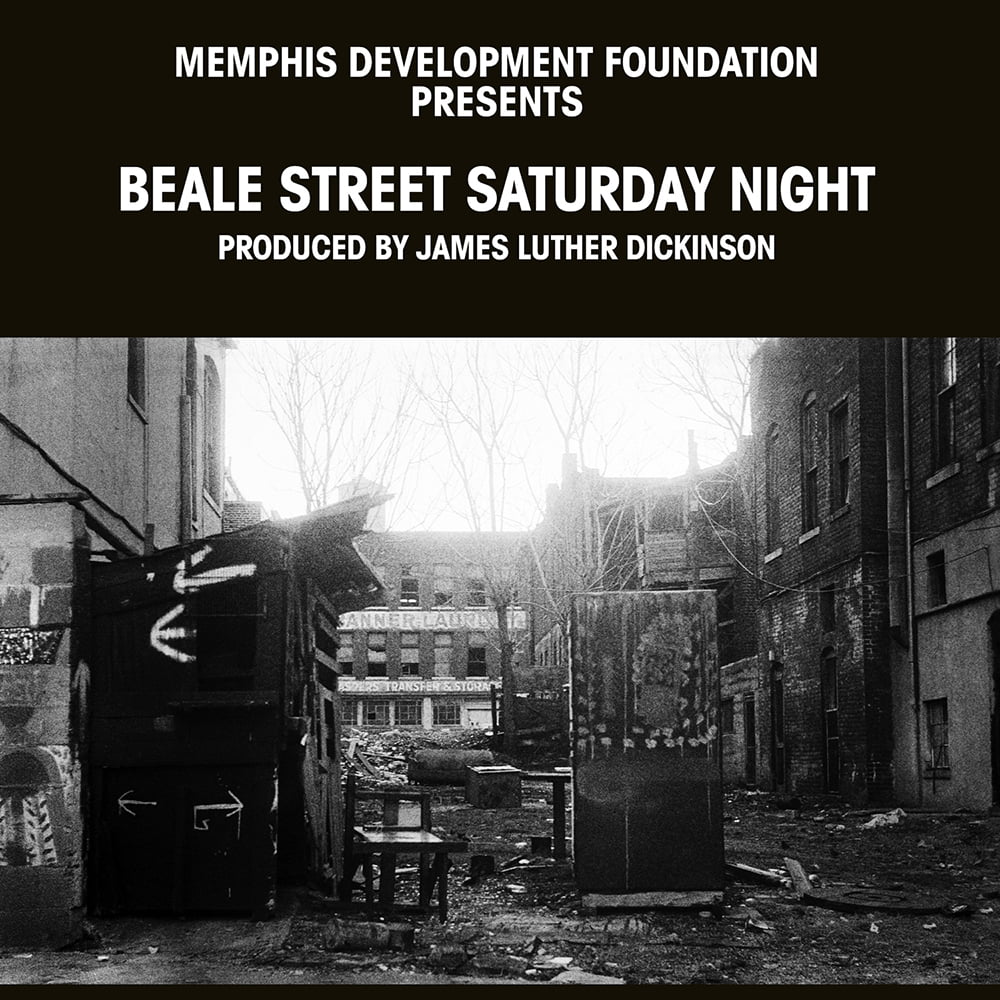

Even at its lowest point, however, the music continued to inspire subsequent generations of musicians grappling with these old sounds and their meanings. In the late 1970s, in an effort to fund the renovation of the nearby Orpheum Theater and to bring attention to Beale’s plight, a local musician and producer named Jim Dickinson produced an album featuring multiple generations of locals feting the famed thoroughfare — older blues acts like Sleepy John Estes and Furry Lewis alongside younger players like Teenie Hodges (from Al Green’s infamous backing band), Sid Selvidge, and Dickinson’s band Mud Boy & the Neutrons.

Listening to the album is like walking up Beale on a lively evening during its heyday, passing by all the bars and brothels, past A. Schwab, all the way up to the banks of the Mississippi. “Jim saw this record as a walking document of the street,” says Pat Rainer, who worked as a production assistant on the original album and oversaw the new reissue from Omnivore Records. “It’s really brilliant the way he conceived it and put it together. The original record had no grooves [between the tracks]. It just all flowed together, from one piece to the next, and that’s the way we’ve maintained it on this reissue.”

Until his death in 2009, Dickinson was one of the best advocates Memphis ever had for its culture and history. As a session player with the Dixie Flyers, he played on records for Aretha Franklin, Sam & Dave, and the Rolling Stones; returning home to the Mid-South, he produced albums by Big Star and, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the Replacements, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and Amy LaVere. Today, his sons Luther and Cody carry on the tradition in the North Mississippi All Stars.

For this aural history of the neighborhood, Dickinson recruited a range of locals, some of whom were old enough to remember Beale’s heyday and others who only knew it as empty lots and decaying buildings. One of the more unusual tracks is performed by a man known only as Alex, who sings “Rock Me Baby” accompanied by a series of loud thwacks. “I don’t know if you can tell,” says Rainer, “but it’s actually somebody chopping wood. Alex was Jim’s family’s yard man, so Jim got him to bring an axe over and they recorded that in his carport. You can hear chunks of wood fly off and hit the speakers.”

If Lauterbach resettles Beale back into its proper place in local and national history, then Saturday Night depicts a scene unmoored in time — less a geographic location than a collective dream of the city of Memphis. The Orpheum was fully refurbished and continues to host concerts and musical productions, yet Beale has suffered a fate some might say is worse than the wrecking ball. “You go downtown on a weekend, and it looks like Disneyland,” says Rainer. “It’s really a shame.”

Photos courtesy of The Library of Congress. See more images of old Beale Street right here.