The End of the Road

They played the festival circuit that Summer and then did a quick 10-day tour of Japan that turned out to be their swan song. Eight shows in 10 days. And then the band broke up. Tony went to play with David Grisman. Ricky and Jerry formed Boone Creek. And Bobby continued his string of what became 27 years playing with J.D.

Tony takes “responsibility” for the band coming to an end. The group was at the top of its game. In talking with Tim Stafford, he alluded to Miles Davis’s best group — the group that recorded Kind of Blue. Yes, that was Miles’ best group, Tony says, but that group wasn’t together a full year, either. In the case of the Crowe band — the band that recorded 0044 — well, Tony suggests, there probably wasn’t “any real room for improvement. I think everybody had sort of a sublime awareness of that. We knew who we were as a bluegrass band. We had all the elements there: the harmonies, the drive, the tune selection. It’s almost like it was so good, it was doomed to burn out real quick.”

For that matter, going back to do another album might not have worked, as well. “That album hit with a pretty hard impact,” Tony says. “Double-oh forty-four hit pretty strong. To have done a follow-up to it a year later would have only done the same thing.”

But there wasn’t the opportunity — though years later, Tony was the key figure putting together the recording known as The Bluegrass Album (Rounder 0140, July 1981) which reunited Tony with J.D., joined by Doyle Lawson, Bobby Hicks, and Todd Phillips. That band, with some variations in personnel, recorded six albums in all for Rounder.

One still wishes the J. D. Crowe and the New South band of 1975 could have lasted a little longer and recorded at least another album or two. Tony acknowledges, “The ’75 band was really short-lived because of me.” Then he adds, “If I hadn’t left, it wouldn’t have stayed together much longer anyway, I don’t think. Ricky had a real staunch traditional side, even back then, and he wouldn’t have hung around. But the legacy still lives on. It raised the bar for what is still going on, to this day, in bluegrass music.” Another time he said, “It’s almost like it was so good, it was doomed to burn itself out real quick.”

Ricky had been talking about starting his own group with Keith Whitley, and he and Jerry had grown close while working in the Gents. But, Ricky admits, “If Tony had stayed two or three more years, I’m sure I would have stayed, because I loved singing with him. I loved making music with him. We’d have done probably another record or two. Who knows? Who knows what that band could have been?”

To be fair to Tony, on Labor Day 1975, he’d been with the band four full years, to the day. And he was only 24 years old. That was a long time to stick with any one band. He’d had the opportunity in March 1975 to play on Bill Keith’s first Rounder album and that was an eye-opener for him. “Keith was able to pull more out than I thought I had in me. As far as I know, that was the first record of significance I had ever guested on. It was probably the most significant recording of my career, in terms of setting a stage for the music that I would be most identified with, even to this day. It was at the sessions for that record that I heard David Grisman’s music … This music that I heard Grisman play on that tape machine, it instantly started flowing through the veins. I’d never heard a sound like that. I was in heaven.” New horizons beckoned.

“I think it was just time for Tony to musically move on,” Jerry says. “It was tough on J.D., and Ricky and I had been thinking of having a band together … forever. It just seemed like it was time, but I wasn’t sure. I really left half-heartedly. I hadn’t been there that long and I really liked J.D. — as a man, as a person. He was great to me. He wasn’t sure about me when I came in but, by the time I left, I really liked him and he was like a father figure to me. I suppose I was looking for that because I was 18 years old. But it was a chance — the same as Tony was doing — it was a chance to go out and do something and put it in our column.”

“Our last song was ‘Sin City,’” J.D. remembers, “and Tony was standing there with tears running down his face. While we were walking offstage, everyone felt pretty sad about the situation, but things have to change.”

Marian remembers how quickly other bands started playing New South material and, by the summer of 1976, she recalls one festival where it seemed that every band was playing something from 0044 — and one group played a whole set that was almost entirely comprised of songs from the album.

Hugh recalls that the album “was not well-received by Bluegrass Unlimited and the bluegrass experts, because it wasn’t the hillbilly stuff that they expected from J.D. Crowe. But, by God, the radio stations loved it and played it. And that’s where its strength came from. Because the next year when Glen Lawson and Jimmy Gaudreau and J.D. Crowe rolled into the parking lot, every goddamn parking lot bluegrass band there was playing ‘The Old Home Place.’”

“Not only is it one of the most important records in our catalog,” says Marian, “but I was in awe of them then, and I’m in awe of them now. There are very few bands about which I feel that way.”

The look mattered, too, she says — a lot. “I remember as much about how they looked as how they sounded. There was a whole feeling that you got from listening to them. Tony wore those colorful shirts and looked kind of like a young poet. J.D. had such stature. He paced at the back of the stage and always was there just at the right moment, at the microphone. They just had such a physical presence. It was easy to be swept away by them.”

Jerry laughs when reminded of the shirts. “We all had really weird shirts, man. If we’d come within 500 yards of a bonfire, there was so much rayon in Tony’s shirts alone that we would have melted. Those were really crazy shirts.”

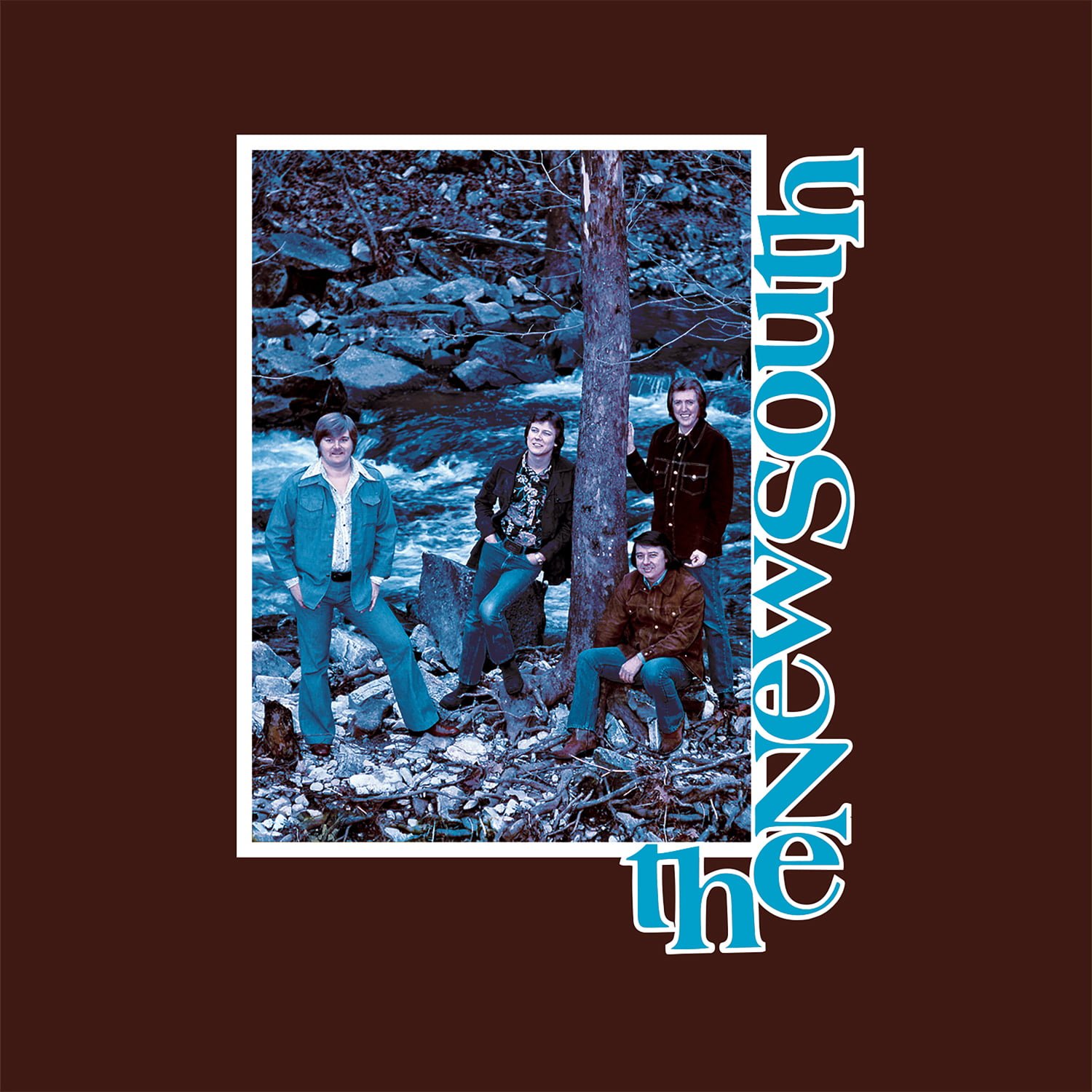

The Album Cover

As something of a postscript, we might acknowledge a little controversy regarding the original cover of Rounder 0044. The photograph was taken, J.D. explained, “at a place called Boone Creek. It’s a big hunting area. Hunt club, is really what it was. There’s a big creek down through there. We went down there. I remember it was real cold, and it gets colder around water. He was running out of film. We were just horsing around, and that was really the only one that turned out, where we was all smiling. You know how that goes.” The only one in which the band was all smiling was the one that was used, surrounded by a dark brown chocolate border in designer Douglas Parker’s rendition. The problem was, some soon noticed, that J.D. had the middle finger of his left hand extended, pointing toward Bobby’s ear. There were some in bluegrass circles who were offended.

“We all wanted to put it out,” J.D. said. “I was kind of reluctant, but the guys, you know how they are, young. ‘Hey, man, let’s put it out.’ We were all kind of an outlaw deal … trying to do something different. Not the same old thing you get to see all the time. Gets boring. You know, I have talked to people who had that record for a year and never noticed that. They weren’t expecting it. They might have looked at it, but it didn’t dawn on them what it was. I was just goofing off with Slone. Really, like I said, it was the only one that turned out where we were all smiling, looking like we were happy.”

After an initial run of about 10,000 copies, Rounder did replace the cover with another image taken later at the same hunt club.

The record was a very successful one for Rounder over the years, and one of the records in which the Rounders take pride of stewardship. The influence the album had was clearly much greater than the sales might indicate. In the first nine months, the total sold was 8,748. It took a little longer before the new cover could be adopted, after the first 10,000 were sold. That was a big seller for Rounder in those days, around the time of America’s Bicentennial.

The album was one which had a profound influence on generations of bluegrass musicians. Alison Krauss enthused about it: “That album — that’s the one! I don’t even know how many times I’ve bought the J.D. Crowe album now. I don’t even know how many. If I can’t find it, I go and get another one. If I can’t find it within five minutes, I go and buy another one.

“All the time! I listen to it all the time! It’s a little scary. Might be time to move on. But I can’t seem to. … It’s so new, even now. Even when you hear all the people who have been influenced by it, it’s still so new.”

Notes

Interviews for these notes were conducted with every member of the band: J. D. Crowe (December 28, 2012), Jerry Douglas (January 5, 2013), Tony Rice (October 17, 2013), Ricky Skaggs (October 22, 2013), and Bobby Slone (December 28, 2012).

Interviews were also done with Hugh Sturgill on December 28, 2012, and with Ken Irwin and Marian Leighton Levy on December 6, 2012. Thanks, as well, to Fred Bartenstein and Tim Stafford for email correspondence, and to J. D., Tony, Ricky, and Jerry for reading over the notes.

In addition, the notes draw on interviews done by Tim Stafford in 2005, which were kindly made available, and correspondence with Fred Bartenstein. Marty Godbey’s biography Crowe on the Banjo (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2011) was an important resource, as was Tim Stafford and Caroline Wright, Still Inside: The Tony Rice Story (Word of Mouth Press, 2010) and Ricky Skaggs, with Eddie Dean, Kentucky Traveler: My Life in Music (New York: itbooks, 2013).

This is part three of a three-part series about the iconic bluegrass album that will be re-released by Rounder Records in an expanded vinyl edition for Record Store Day 2016.