Last October, Tommy Emmanuel took a fall and busted a couple ribs at a concert in Toronto’s Massey Hall. While the injury led to some postponed concerts (although he performed the full show in Toronto), it also produced, in its own way, a very welcome result: Emmanuel’s first solo studio album in a decade.

From his home in Nashville the guitar master told BGS that he experienced a burst of creativity while recuperating at home. “I’m like, ‘Wow, I’ve got time to write and play and experiment.’ All of a sudden I’m a kid in a candy store again.” He also confided that he disregarded his doctor’s advice on how long to rest and was back on the road after “going into hibernation” for three weeks. “If I had taken my doctor’s advice, he’d have set me back 20 years. I’m a moving-forward guy,” he explains.

Emmanuel may not pass muster as a medical doctor, but he certainly qualifies as a doctor of guitar playing. In fact, an authority such as Chet “Mister Guitar” Atkins bestowed Emmanuel with his Certified Guitar Player honor, one of only four CGPs that he handed out during his lifetime. An Australian native who moved to Nashville in the early 2000s, over his long, exceptional career Emmanuel also has earned a GRAMMY, many various music awards in Australia, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Guitar Museum, and he is a Member of the Order of Australia.

Never one to rest on his laurels, Emmanuel delivers perhaps his most eclectic album with Living In The Light. While it is definitely stocked with exquisite acoustic picking, the album also contains some more experimental tracks. On “Intuition #25,” for example, he uses some delay pedal wizardry to reimagine an old instrumental. He also handles lead voices on a trio of tunes, including his take on an ‘80s Australian new wave pop hit “Maxine,” the even older, yet still timely “Waiting For The Times To Get Better” – previously recorded by folks like Crystal Gayle and Doc Watson – and a funky, inspiring number, “Ya Gotta Do What Ya Gotta Do,” written by his buddy Michael “Mad Dog” McRae.

Emmanuel may have turned 70 this year, but he exhibits a perennially youthful passion for music. As he explains it: “Music is my blood. I love it.”

Living In The Light is your first solo studio album in around a decade – how did it come about?

Tommy Emmanuel: Well, after I broke my ribs [last year], I knew I had to surrender from touring, and so I was forced to come home and hibernate – try to get my ribs fixed or healed. When I got home, even though I was kind of slightly medicated because of the pain and everything, I was in a great place. I didn’t have to walk out the house and fly somewhere and go play shows. All I had to do was be here and get healed. … Probably the best thing to happen to me was falling, breaking my ribs, and then being poured into a break, because then I got the whole record together.

The first thing I wrote was “Black and White to Color.” It’s like full of energy, full of spark, it’s got everything. It’s completely adventurous and it just came out of nowhere. I started playing some of the guitars that I don’t take on the road, and all of a sudden I got this idea in the way it went. And that’s kind of like how it all came together.

How did you hook up with Vance Powell as your producer?

My great desire was to work with Vance Powell, who I had heard and discovered through Chris Stapleton, Jack White, and people like that. I just loved his work. It was so real and so pure. And I thought, “I’ve got to work with this guy.” He is so busy that last year when I tried to book him, he could only give me four days this whole year, right? That’s how busy he is. So, I booked him. And we cut the whole album, finished, [and] mixed it in four days. That’s it.

I got to tell you that Vance is my kind of guy. There’s no bullshit. There’s no wasting time. We start at 10, we finish at 6. That’s it. We didn’t work all night and wear ourselves out and labor over take after take after take after take. People are always surprised when you say, “Well, I just did it in one take.” They’re like: “What? That’s impossible.” No, it’s not. I have to do it every night when I walk on stage.

You sing on a couple songs on this album, which is more than you usually do.

I’ve worked with some great singers and I’m not one of them, but there’s an honesty about what I do. If you sing something because you really love it and you love to sing it, that’s a good enough reason, you know? I don’t have to prove that I’m the world’s best singer, because I’m not.

Where did the album title, Living In The Light, come from?

I’m glad you asked that. This is how it all started. I was out with my buddy, “Mad Dog.” Him and I are early morning walkers. We go down to an area called Percy Priest Lake here in Nashville and there’s a three-mile walk. We usually do that at like 6 a.m. We’ll meet there and we’ll walk the three miles and talk and laugh and carry on.

And he was amazed how well I looked. He said, “Brother, I’ve never seen you looking so well. You must be living in the light.” And when he said that, I went: “That’s it!” I just thought: “Living in the light. Wow, this is what it’s about.” We’ve all had enough darkness. Let’s get some light.

Can you talk a little about the guitars you use here?

They’re mostly my touring guitar, my Maton Traditional, it is called. When I did “Ready for the Times to Get Better,” I borrowed a Martin D28 because it was just the right sound for that track. When I played “Little Georgia,” I used my Larrivée, which was a different, Canadian guitar and it just sounded just right for that track.

Did you know which guitar you wanted for “Little Georgia” or did you try your Maton guitar and then go, “I don’t think it’s the right match”?

I went straight to the Larrivée because the guitar has a sweetness and it has great sustain. When you play it in a kind of close-to-the-microphone, intimate way, it’s like everything you need is right there, and it’s beautiful.

I’m a song player, I’m a song person, and so I need the right voice to tell the story.

And on instrumentals, your guitar is like your voice?

That’s right. I tell stories without words. That’s my job.

Bluegrass has been influential in your music, but on Living in The Light it seems less prominent than other albums.

I tend to not think about putting a label on it or a genre. Bluegrass music is to me as soulful as R&B or as in-your-face as rock and roll. So I never worry about someone saying “Oh, is this really bluegrass?” or whatever… I’m hardly bluegrass, but yet I am bluegrass in many ways. But I’m also R&B and I’m rock and roll, and I love pop music. I just like good songs and good music.

What American music did you first connect with growing up in Australia?

My first love was Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams. And then I heard Jim Reeves and Marty Robbins. Then, when I was about seven, I heard Chet Atkins and that galvanized me. That sent me on another path and changed my life completely. Because when I heard Chet Atkins, something changed inside me. I heard a sound that I’d never heard before and I just knew that’s what I wanted to do. “I want to do that – whatever that is.” I didn’t know how to play like him at all. But I worked it out myself.

And because, you got to remember, this is the early ‘60s. There were no music shops. There were no guitar teachers. There was no video. There was no TV in Australia that we could see live music on. It was all either on the radio or the record player. That was it.

To have Chet Atkins take you under his wing must have been an unbelievable dream come true.

Exactly! You said it, right on. When my dad died, I was 10, I kind of retreated into Chet’s records. That’s what got me through that terrible loss and that period. And I ended up writing a letter to him and he wrote back and we stayed in touch. We were like pen pals and he stayed in touch with me.

Then somebody sent him a tape of me playing when I was about 18 and I get this letter out of the blue. It’s from Chet saying, “I heard your tape and when you come to Nashville, you call me and here’s the number.” He gave me his office number. I came to Nashville to meet him in 1980 and we were like family when we got together. He was my daddy, you know.

You’ve hosted a guitar camp for several years. Is that a way for you to mentor the next generation of musicians, similar to what Chet Atkins did for you?

It’s not just my camp. It’s nearly every night of my life, wherever I am. I meet young players and people and I try to be a positive force for them in their life. I try to show them that if you’re willing to put the work in, this is what’s possible, because I came from nothing and from nowhere, and this is what you can do. You’ve just got to stick at it. Do not quit. You know, stuff like that. But also, my camps give me a chance to talk to people from the perspective of: “I’m an example to you of someone who makes a living playing the guitar. I don’t do anything else.”

Most of the teachers that I employ are much better teachers than I am, but I have fun talking about what I do and demonstrating stuff that shows people behind the wizardry that they’re seeing with their eyes. I can open the window on it and say, “Look in here, this is what I’m actually doing.”

Congratulations on turning 70 earlier this year. I was wondering how your playing style has evolved. Have you had to make any adjustments to the way you play guitar?

Here’s the truth. I’m pushing harder than ever. I’m getting out there like a kid having the time of my life. I’m bulldozing the shit out of everything. I’m having a great time. And I feel energized, inspired, and I just feel like I don’t have that anxiety of, “Oh I’ve got to get out and prove myself.” I just get out and play because I love to play and take people with me. It’s as simple as that.

Of course, there are certain things, like some songs that I try to play that I struggle with now, because my skills in some areas are not what they used to be. I can hear myself playing a song 30 years ago and I go, “Holy shit, I can’t play anywhere at all like that now.”

But I can do other stuff that’s more meaningful to me now, you know. So, my focus has changed. I know that I don’t have the skills in some areas that I used to have but I’ve been there and done that, so now I’ve got this. And I’ll try to do my best with whatever I’ve got to give the people right now at this time in my life.

It certainly seems like you also now have the freedom to make the music that you want to make.

That’s exactly right. And I don’t labor over stuff and I’m not a perfectionist. It’s about telling the story and capturing the feeling of the whole thing, even if it has a few rough edges. If this is the one that has all the feeling, [then] that’s the one I’m going to live with. I’m not going to try and polish it up.

I’m just going to say, “This is it and here’s the story,” and that’s it. … It’s only the people who are willing to be true to their art [who] are the ones that the public actually really likes – all the other stuff is contrived.

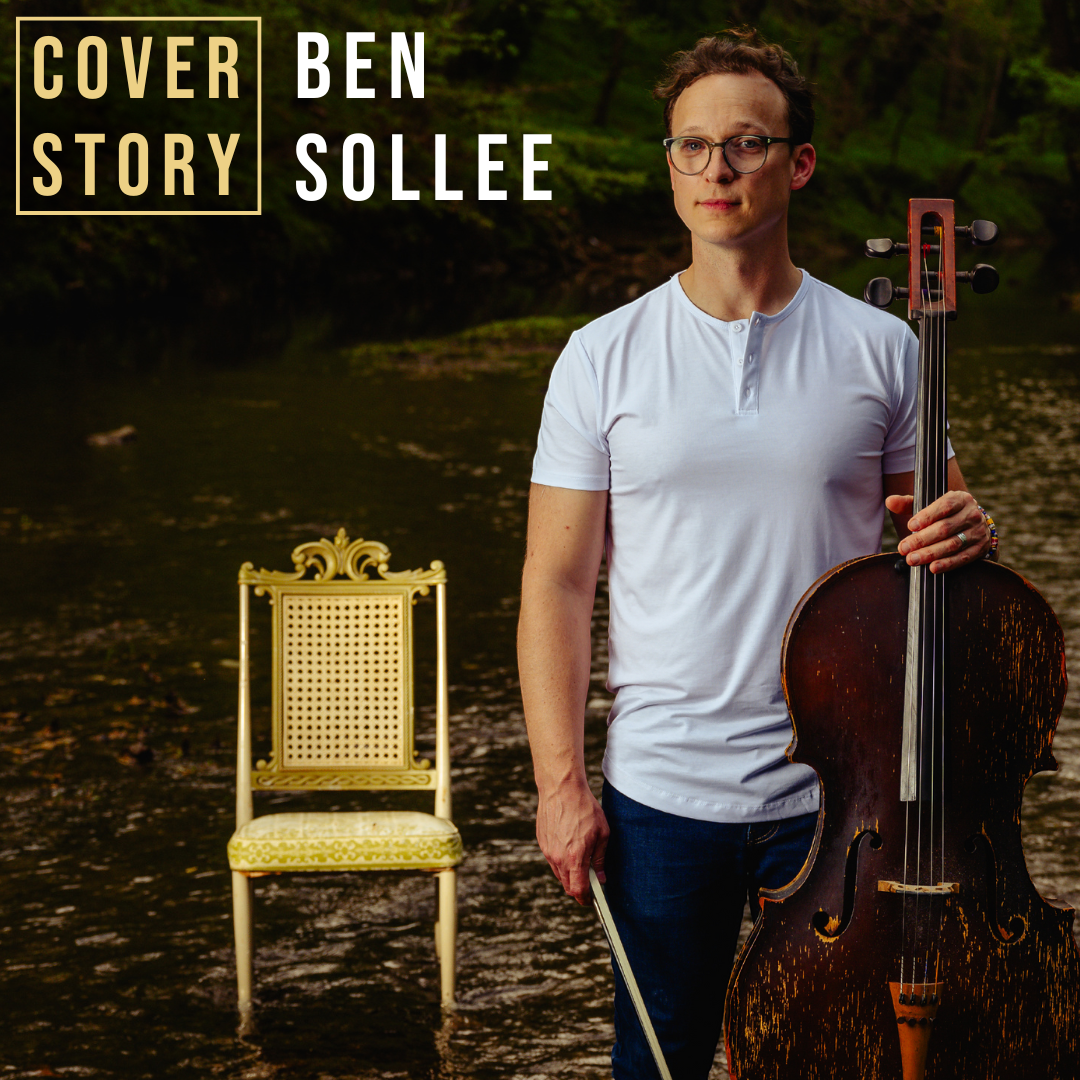

Photo Credit: Simone Cecchetti