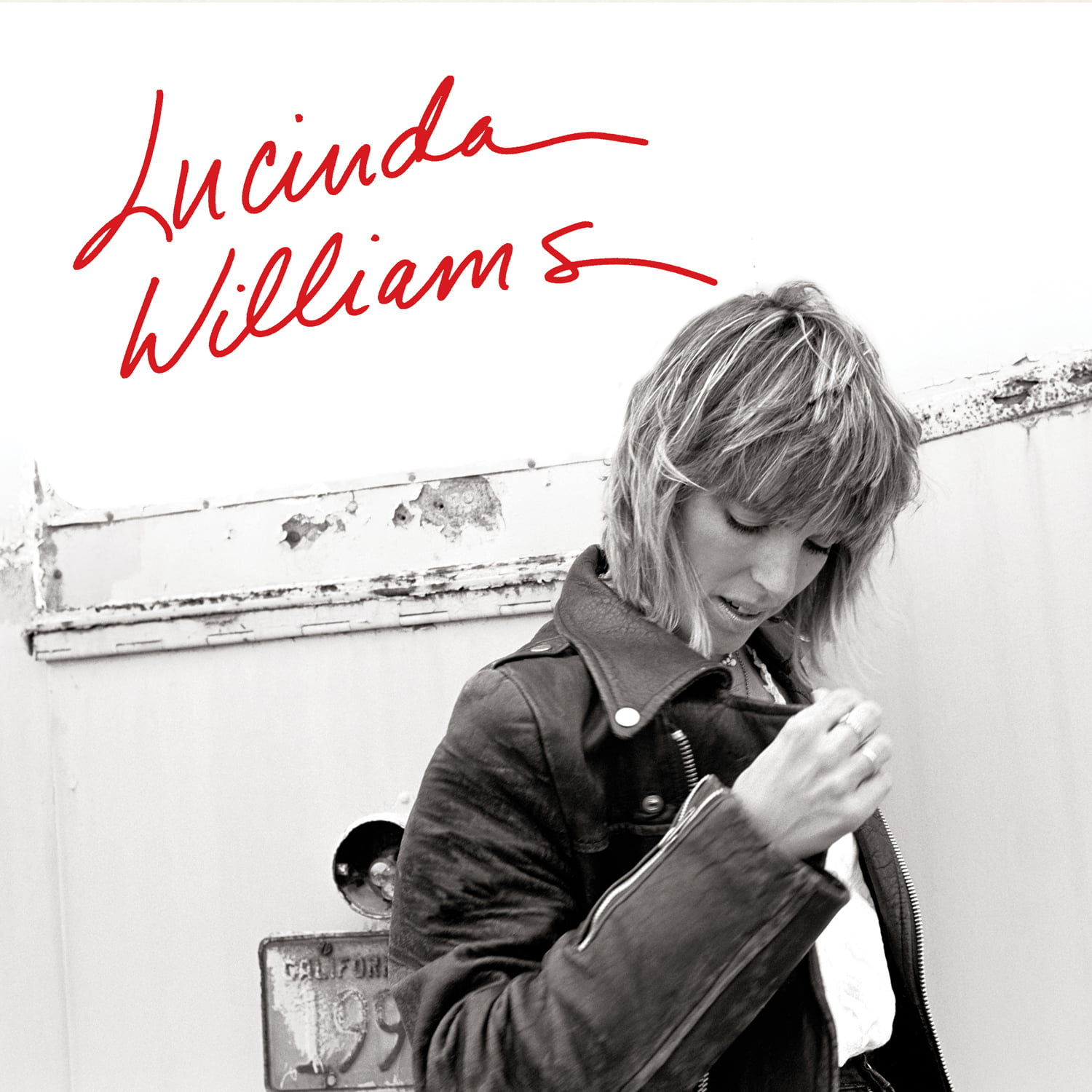

Because she spent so much time between albums — eight years between her second and third, six between her fourth and fifth — Lucinda Williams has been assigned a reputation as a perfectionist, as though country music must be approached with the sonic exactitude of prog-rock. But the near-decade interim separating 1980’s Happy Woman Blues and 1988’s Lucinda Williams doesn’t indicate a maniacal pursuit of a specific vision, although these songs are as close to perfect as just about any country album of that decade. Instead, the Louisiana-born, Los Angeles-based singer/songwriter spent those years redefining her sound away from acoustic blues to something closer to country-rock, moving out of Texas for Southern California, and trying like mad to sell herself to a record label. Recording Lucinda Williams took less than a month. Getting somebody to give a shit took significantly longer.

As Williams has said, in the 1980s, she was perceived as too country for rock radio and too rock for country radio. Lucinda Williams continually writes and rewrites its own rules, with each song presenting a slightly different definition of what “country” and “rock” might be. “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad” opens the album with a bouncy drum beat and a bright guitar lick, with Williams rushing through that title phrase, jumbling the words together as though mid-sprint. It’s full of hope and intense desire, both echoed on the story-song “The Night’s Too Long” and the list of demands “Passionate Kisses.” The blues still informs her songwriting, albeit in different forms: “Am I Too Blue” adheres to the country blues setting, but “Changed the Locks” is something new for Williams, a low-down urban blues tune surprisingly lascivious in its harmonica riff and humorous in its lust and self-delusion. “I changed the lock on my front door so you can’t see me anymore,” she testifies. “And you can’t come inside my house, and you can’t lie down on my couch.” Few singers — including Tom Petty, who covered the song in 1996 — could draw so much sexual promise out of the word “couch.”

Like Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, Lucinda Williams has become symbolic of the old art-versus-commerce debate, a manifestation of the grievous oversight of major labels and radio programmers, held up as evidence that the business of music, by default, ignores good music in favor of marketable product (as though there’s no overlap). Released in fall 1988, the album became a cause célèbre in Nashville, particularly among female musicians: Patty Loveless covered “The Night’s Too Long” in 1990, Mary Chapin Carpenter enjoyed her biggest hit with “Passionate Kisses” in 1991, and Emmylou Harris sang “Crescent City” on Cowgirl’s Prayer in 1993. You could almost reconstruct the tracklist with excellent covers.

Generally perceived as much more conservative than the audience or the artists it ostensibly serves, in the late 1980s, country radio was only just shifting away from the gauzy nostalgia of neo-traditionalists and the last sputterings of legacy artists and moving toward the hat acts who would define the genre into the next decade. In the fall of 1988, when Lucinda Williams finally made it to record store shelves, Dwight Yoakam, Rosanne Cash, Tanya Tucker, and the Oak Ridge Boys all enjoyed number one country hits. Noted country eccentric Lyle Lovett enjoyed two gold records in 1988 and 1989. Mainstream country music has become a thread-bare strawman for alt-country and roots audiences, but it wasn’t just the industry’s prudishness that kept Lucinda Williams off the charts and the playlists, despite that story’s persistence over the years.

It wasn’t something in the lyrics, either. There were rumors that radio executives objected to the prurience of the line, “His back’s all soaked with sweat,” sure to send housewives into a tizzy, but “The Night’s Too Long” was soon a single for Loveless. Williams’ voice was cited as a potentially alienating factor, one that blurred its syllables around the edges, slurring its speech after too many cold Coronas in some lost honkytonk. Williams replaces the recognizable twang with something more idiosyncratic, something more rooted in geography, something that was, at the time (and definitely still is), as foreign to country radio as ouds and zithers. Lovett’s deadpan drawl and Yoakam’s Bakersfield barb were similarly iconoclastic, but they were guys in an industry that preferred women more easily manageable and malleable (which is not to dismiss the self-possession of Williams’ female contemporaries, but more to speak to the considerable feat of their success).

Ultimately, Lucinda Williams just wasn’t designed for radio. It wasn’t meant for the mainstream. It has become exactly what it was supposed to be: a cult record, a foundational document, the wellspring of a new strain of music that would eventually be labeled alt-country. The Jayhawks might have debuted two years earlier, and Uncle Tupelo might have named the magazine, but this album — more than any other — revealed the limitations of Nashville and its neglect of very large swathes of country music listeners. Williams staked out all new territory. She had had a fairly itinerant life, born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, but raised elsewhere. She’d lived in Arkansas with her father, the poet Miller Williams, then Texas, where she made two albums of tentative country blues that even her most avid fans don’t spin much anymore. Most of her 1980s were spent in Los Angeles, which is perhaps the most significant aspect of Lucinda Williams.

That city was a mecca for country music as early as the Great Depression, when itinerant Southerners and Midwesterners moved west looking for work. Singing cowboys proliferated throughout the 1930s and 1940s before they were eventually replaced by crooners and rock stars. The term “country-rock” was coined in Southern California, thanks to Gram Parsons and the Beau Brummels (who recorded the overlooked Bradley’s Barn with Owen Bradley in 1968). Around the same time, Bakersfield became a powerful force in country music; roughly two hours north of Los Angeles, the town supported more than its fair share of roadhouses and honkytonks, where country music was played on electric guitars with strong backbeats and where Buck Owens and Merle Haggard cut their teeth.

Williams might have appreciated those artists, but at least on her self-titled album, her sound never borrowed much from those scenes. Instead, Lucinda Williams sounds bound to a city that, in 1988, would have still been viewed by those back east as a den of crime and ersatz glamour — cocaine and liberalism, yuppies and punks. The city’s punk scene had somehow made room for twang, with X spiking their punk with rockabilly (and sharing stages with Dwight Yoakam) and Lone Justice sneaking out of the underground with “Ways to Be Wicked.” As Williams told Spin in 2016, “There was an actual really cool thing going on out in L.A. in the mid-‘80s, [acts] like the Long Ryders, the Lonesome Strangers, the Blasters, Rosie Flores, and X. I was just opening for bands, and a lot of labels were noticing me and would come to my gigs, but nobody would sign me; they all passed on me, even the smaller labels like Rhino and Rounder.” It took an English label to finally sign her.

To call Rough Trade a punk label would be to minimize the breadth of its catalog, which included a remarkable mix of industrial (Cabaret Voltaire), punk (Stiff Little Fingers), post-punk (the Pop Group), pop (the Smiths), and things in between (Panther Burns). The label opened an American office in 1987, with a mission to sign more U.S. acts. Still, Williams was a departure for the label — a risky bet that paid off. Lucinda Williams peaked at 39 on the Billboard album charts and spawned two EPs in 1989. Her next album would be released by an imprint of Elektra Records, the one after that by Mercury.

The portrayal of Williams as somehow outside the industry — as an alternative to the mainstream — persists today, perpetuated by the woman herself. Williams has continually distanced herself from what she described to Billboard as the “straighter country music industry of Nashville.” In response to that interview, Chuck Klosterman calls her out in Sex, Drugs, & Cocoa Puffs and predicts “Lucinda Williams’ music won’t matter in 20 years. Oh, she’ll be remembered historically, because the brainiacs who write pop reference books will always include her name under W. She’ll be a nifty signpost for music geeks. But her songs will die like softcover books filled with post-modern poetry, endorsed by Robert Pinsky and empty to everyone else. Lucinda Williams does not matter.”

As with so many Klosterman statements, it’s provocative, entertaining, and demonstrably untrue. Fourteen years later, Lucinda Williams still matters — as a songwriter routinely covered by artists in a range of genres, as an industry cautionary tale, as an alt-country figurehead, as an artist boldly reinventing herself on her most recent albums. And Lucinda Williams matters perhaps even more — not because we’re still talking about it 30 years later, but because no one is really from Los Angeles. At its heart, this is an album about small-town transplants in big cities, about Southern ex-pats far from home, and few artists have taken up that musical sensibility as confidently or as comfortably as Williams, an LA native displaced in L.A.

“The Night’s Too Long” makes the theme literal, describing a young woman who sells her belongings to move to where things are actually happening. Williams gives her a name, a job, and a hometown in the song’s first line: “Sylvia was working as a waitress in Beaumont.” She moves away to “get what I want,” which might as well be the laundry list of demands on “Passionate Kisses.” Home and travel and loneliness and melancholy suffuse these songs. “Crescent City” recounts a trip back to Louisiana, where she — maybe Lucinda herself, or perhaps Sylvia — hangs out with her family, listens to zydeco, takes rides in open cars. “Let’s see how these blues’ll do in a town where the good times stay,” she sings, as Doug Atwell’s fiddle solo winds its way through those familiar backroads and across that “longest bridge” over Pontchartrain. It’s a poignant song for any listener who doesn’t live where they grew up. It’s the sound of rediscovering the joy and reassurance of home, a theme that ultimately transcends genre, industry, and even performer.