There is a crossroads of 1970s folk, blues, and nonconformity in Texas. Ask students of it about Rodney Crowell, and chances are, visions of a lean, baby-faced guitar picker belting out “Bluebird Wine” at Guy and Susanna Clark’s kitchen table flood their brains. It’s a scene from Heartworn Highways that is both wild and tender, captured when Crowell was just 25 years old. Today, that Houston kid is 72. He’s won Grammys, topped charts, pushed the musical and literary boundaries of songwriting, and continued to write and record, as friends and mentors passed away.

Produced by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, Crowell’s new album The Chicago Sessions is the latest evidence that Crowell isn’t just continuing: He keeps getting better. The 10-track collection was recorded live in Tweedy’s warehouse studio, perched atop a northwest Chicago building. Crowell had always wanted to record in Chicago. “That would be Chuck Berry, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, John Prine, and Steve Goodman who have a lot to do with that,” Crowell says. “The Rolling Stones, as soon as they got to America, said, ‘Let me go to Chicago.’”

The ghosts and recordings that drew Crowell to Chicago did right by him. Surrounded by his own go-to players (guitarist Jedd Hughes, pianist Catherine Marx, and bassist Zachariah Hickman) plus two drummers of Tweedy’s choosing, Crowell sounds smooth, sly, and often downright happy. “It was liberating. I felt no pressure whatsoever,” he says. “If I’m producing myself, I’m wearing one too many hats. I’m helping everybody else and making sure I can make them get to where we’re all going, sometimes to my own detriment. But with a producer like Jeff Tweedy or Joe Henry, hey, I’m freed up. I’ll just play and sing.” He pauses, then adds, “I’m really good when I just play and sing.”

Gratitude and race, self-worth and religion, cynicism and hope: The songs on The Chicago Sessions cover ample ground without feeling disconnected.

A swampy shuffle, “Somebody Loves You” is a master class on cultural commentary and exposing shifty motivations. With subversive conviction on par with Tom Waits, Crowell implicitly questions people in power who shush the disenfranchised with assurances that somebody — in this case, Jesus — loves them.

There’s lead in the water, knees on your neck

Son of your father, born to neglect

Mind your own business, siren gone’ wail

Make one false move brother wind up dead or in jail

It’s been 400 years right down to the day

Somebody loves you, least that’s what they say

“As a writer, I need the stakes to be high,” Crowell says. “I am hard on myself as a singer because I’ve heard Ray Charles, and I’ve heard Don Everly. I’ve heard Aretha Franklin. ‘Look, man,’ I say to myself: ‘You don’t have that voice. But you gotta deliver on what you got.’”

Crowell confesses that really, he didn’t care for his own voice much at all until he was about 50 years old. “I knew I was writing — I developed early as a songwriter,” he says. “But I wasn’t delivering at the level I wanted to deliver when I would record those songs. I stayed with it, and I outgrew it.”

But to the rest of us, Crowell’s voice is and always has been lovely: steady, expressive, and charged, like an electric orb capable of warm light or hot sparks. Another album standout, “Loving You Is the Only Way to Fly,” which Crowell co-wrote with Hughes and Sarah Buxton, is a pining love song, perfectly executed. The sweet keys and strings are timeless. Tweedy’s production throughout the record is exquisite. “Making Lovers Out of Friends,” another track off The Chicago Sessions, is a testament to the power of a great producer and a great song, reminiscent of Billy Sherrill’s work with Charlie Rich, both in sonic texture and achievement.

As a writer, Crowell doesn’t cut himself any slack as a protagonist. Over the years, he’s developed a habit of being hard on himself in lyrics — or perhaps, of seeing himself clearly and confessing self-perceived shortcomings. “Lucky,” a piano-driven song he wrote as a birthday gift for his wife Claudia, plays with a bit of exasperation: “Anyone with eyes could see, I’d had about enough of me.” The record’s sauntering blues track “Oh Miss Claudia” hits similar ideas.

But it’s not just songs written recently. The Chicago Sessions also includes Crowell’s self-penned “You’re Supposed to Be Feeling Good,” originally recorded by Emmylou Harris in 1977. Oscillating between stripped-down acoustic and groovy full-band swells, the song picks up the same self-deprecating themes: “You’re supposed to be in your prime / You’re not supposed to be wasting your time / Feeling like you’re down and out over someone like me.”

Crowell often credits friends or lovers with seeing the best in him or pulling him through tough times. “I know it seems like that, honestly,” Crowell says of being hard on himself, then laughs a little. “They deserve the credit.”

Crowell doles out credit when it comes to his craft, too. “Guy and Townes [Van Zandt] were right there at the beginning of my development,” he says. “Guy was a generous mentor, in a way — the way we talked about writing. Discussed it. Examined it. Townes was around intermittently because he was traveling a lot. When he was around, he was a bit jealous of my relationship with Guy. And rightfully so. He and Guy were tight friends before I ever came around.”

Then, Crowell sets the scene: “Did you ever see Don’t Look Back? Remember Bob Dylan and Donovan in the hotel room? Donovan plays this kind of sappy, folky, flowery song for Bob Dylan, and then Dylan picks up a guitar and sings, ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.’ He slaughters Donovan’s song with a masterful song. Well, I had that same experience with Townes, just in the privacy of the breakfast table at Guy’s house.”

Crowell pauses, then explains, “‘No Place to Fall’ is exactly what happened. I was sitting there, going on about something, and Townes said, ‘I’m going to play you a song.’ And it just crushed me.”

In a nod to his artistic education and one of the figures who delivered it, Crowell recorded “No Place to Fall” for The Chicago Sessions. “Listen, if Townes had not crushed me with ‘No Place to Fall,’ I wouldn’t have written ‘Till I Gain Control Again,’” Crowell says. “It was like, ‘Oh, that’s what it is. That’s what you aim for. If you don’t aim for that, you’re selling the whole deal short.’”

Crowell pondering where he’d be without Van Zandt’s lyrical gutting spurs a bigger question: Where would roots music be without Crowell? His sheer musicality, instincts, and determination to recognize greatness and then, instead of feeling defeated, aspiring to match it in his own way, has propelled an entire art form forward.

Widespread mainstream success — especially at the high levels Crowell has achieved — can lead to oversights of actual artistic achievement. While Crowell himself often describes his relationship to Van Zandt and Clark as one of student and teachers, over the last five decades, Crowell’s consistently brilliant output has proven he shouldn’t be framed solely as a disciple of songwriting giants, but as their peer.

Clark and Van Zandt were the sons of attorneys. Crowell was the son of a heavy drinking dive bar musician, born on the wrong side of the tracks. He comes from East Houston, historically an industrial sector, marked by factories and proximity to oil refineries. He’s never shied away from his past and people. “Houston, Wayside Drive — Avenue P, where my parents lived when I was born,” Crowell muses. “It always meant something to me.”

After a brief stint in college, Crowell sought knowledge on his own — perpetually. His lilting cadence and thoughtful care with language is like that of a professor, especially when he dissects music or history. His curiosity isn’t just intellectual, but spiritual, too. He explores and sings about acceptance and peace, especially when talking about friends, himself, or even people with whom he disagrees. The Chicago Sessions’ closer, “Ready to Move On,” is a meditation on balance, and Crowell’s pursuit of it.

“I’m sitting out here, listening to the wind go through the trees, thinking, ‘Wow, I live on top of this hill, surrounded by all this green. Man, how did I get here from East Houston?’” Crowell is talking about his home, just outside of Nashville. “The way I got here was, I fell in love with the sound of these songs, from my father singing them to me when I was a wee child. It makes me humble, in a way. God, I have gratitude for that. Whatever my sensibilities are that came through DNA from my parents that made me so attuned to the sounds that were coming at me, all the way through Merle Haggard, the Beatles, anything that moved me. It’s like, ‘Whoa, man. What a lucky break I got.’”

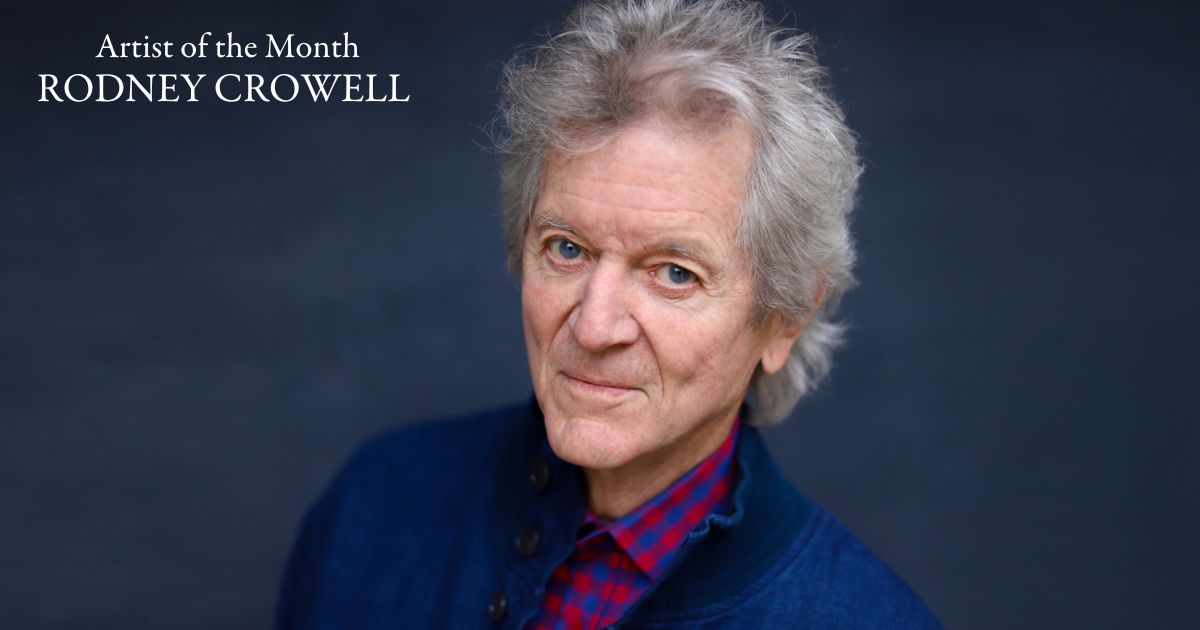

Photo Credit: Claudia Church