(Editor’s Note: Sign up here to receive Good Country issues when they launch, direct to your email inbox via Substack.)

I bet in the next few years, an expert taxonomist will come by and tell us exactly what country music is – and that this definition will create endless arguments. In the last few months, this argument about what exactly country music is has been growing louder. Jason Isbell has been fucking around with Nashville for decades, playing the field between rock, country, southern rock, country rock, and classic country. (He has recently said that he considers himself a rock singer). Adeem the Artist, the infamous cast iron pansexual, says that they are a folk singer. Willi Carlisle, a folk up-and-comer, has released Critterland, a certainly country album. On the other hand, Maren Morris released two singles last fall which were about burning Nashville to the ground, yet they’re perhaps the most country songs of her career – in terms of how she tells stories, how the bridges work, her vocal tones, and even some of the instrumentation. It seems lately, country is both everything and nothing.

Amanda Fields’ 2023 project deepens this ongoing problem. The album, What, When and Without, is a complex artifact of her own wrestling with genre, history, and biography. It slides into that complex sorting of genre and feeling that is key to Nashville right now. Fields calls this a country album – lushly produced, thick with strings, and dense with vocals, reminding one of an updated countrypolitan record – but sorting out what that means comes with a history of playing and listening.

Fields has a reputation on the bluegrass circuit, often an insular genre with an insistence on a certain kind of purity. She recognized how those questions of purity often don’t pay the bills, and her first major recordings were on a series of bluegrass cover records, called Pickin’ On – recorded by prominent bluegrass studio musicians, there are dozens of them, the artists covered include the expected (Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash), the unusual (Blink 182), to the fully flummoxing (Modest Mouse). Though Fields did not play on all of these records, she talks about them as an integral understanding of herself as part of a musical team: “When I look back on my experience within the ‘genres’ I’ve taken part in, I think about the groups of people I worked with… When I worked on Pickin’ On, I got that gig because of who I was hanging out with and playing music with at the time. I sang ‘gospel’ when I was growing up, because that was the community within my proximity.”

Proximity is a complex question for Fields. She has close ties to the bluegrass community, and there is something intriguing about the idea that genre is a social category – one about who one is near, or what the audience and the performer agrees to participate in. Yet there is a kind of roving that occurs here too; for Fields, roving is both a history of moving around geographically and, as she says here, moving from music that she considers bluegrass or gospel or country.

Fields moved around a lot as a child. Though she was born in Appalachia and currently lives in suburban Nashville (right next to Loretta Lynn’s old house), the line between these two legendary destinations was not direct.

Asking Fields about these roots – expecting a standard line in response – she honestly describes the complexity of her raising: “I’m originally from the mountains and it was my anchor growing up, but my dad moved us around a lot. He was one of those people who felt there was more to life than what was available to us living in that area, so he took job opportunities that carried us away from the mountains. I didn’t like that, because I was always longing to be ‘home’ with the rest of our family. I lived for summers and holidays when I got to be in Virginia and East Tennessee. Playing and listening to country and bluegrass music was my way to experience home when I couldn’t be there physically.”

This moving and returning is a common note for country musicians. Listening to her talk about the juxtaposition of moving, returning, being forced to leave, and finally finding home in an idea more than a place, I am reminded of Tanya Tucker or Merle Haggard. Tucker’s early childhood had a father who moved her from Arizona to Las Vegas to finally Nashville, chasing an acting and singing career. She broke out as a singer who fused a desire for rock and for country. It is similar to Haggard’s talk of moving – to California with his family as a consequence of economic disenfranchisement – and spending the rest of his career chasing economic stability. That idea was perhaps best written about in his tragic ballad “Kern River,” with its opening line, “I grew up in an oil town, but my gusher never came in.” (A Fields original from well before What, When and Without, “Brandywine,” strikes a similar note.)

This connection to Tucker, Haggard, and other classic country singers suggests that Fields landed not necessarily in a place, but as she says, in a music which has tight connections to place. What, When and Without, a classic country album, is infused with this kind of nostalgic listening.

Asked about her relationship to figures like Loretta Lynn or Haggard, she answers carefully: “Most of the music that really stirs my soul is older. I listen to all my friends’ new music and I’m always hunting something fresh to connect with, but on a day-to-day basis, I’m usually listening to the same stuff I’ve always loved. I’m talking Tammy Wynette, Loretta Lynn, Conway Twitty just about everyday. Classic country is what excites me (especially when I discover something I haven’t heard) and those familiar sounds and voices help me regulate my body’s nervous system.”

The album, rooted in those sounds, contains a deep knowledge of genre. Its ability to move between old school country, bluegrass chops, and deep, modern desire is one of its strengths. Figuring out how to sound both modern and historical is something Fields achieves with some skill. If her commitment to genre has a loose, rootless quality – or at least one which floats and lands depending on aesthetic or social need – then how she considers time has a similar quality.

Maybe her early commitment to bluegrass, a genre who remembers more than it forgets, and faces backwards as much as it faces forwards, and which was complicated by how hungry those covers were, suggests one way of bridging eras. But, her recent work, crafting contemporary studio craft with the careful polish of Studio A aesthetics is another. Asking her about memory and nostalgia, she again answers carefully: “One thing that was very intentional with the album was the pace. I think that going slowly is nostalgic in a way, because society and industry move so fast nowadays. I usually walk slowly and I talk slowly compared to most of my peers. My body responds to tempo and dynamics and I wanted to invite the album’s listeners to slow down with me.”

The slowness of the album can be heard in how she starts many of the tracks. There is often an instrumental intro where one waits a significant time for the vocals to be introduced and on occasion there are gaps, where her vocals recede and the band takes over – though the band itself is also quiet. There is a quality, listening to the work, of a kind of courtly two-step, the band asking Fields to dance, and vice versa.

The very first song, “What A Fool,” begins with brushed drums, and has a quite lovely open-ended moment where the pedal steel becomes central. On “I Love You Today,” the old-fashioned cheating song, heartbreak is introduced via an elegant, western swing sound, not outside of Lovett at his best. The last song, “Without You,” plays drums as solid and regular as a heartbeat. It’s another heartbreak song.

The pedal steel is crafted by Russ Pahl, who has been playing for decades. He has been nominated by the Academy of Country Music for his work on the steel guitar three times and for specialty instrument once, between 2004 and 2021. Before that, aside from being an in-demand studio musician, he was part of legendary Great Plains, another band who was excellent at moving between genres, across time, and throughout modes.

Talking to Fields about Pahl, she noted how good he was at not only playing, but matching vibes in the studio: “He came across very quiet and contemplative in the studio and I think he ‘got’ the vibe right away. After a song or two, he said, ‘…this ain’t Zip A dee Doo Dah.’ And it wasn’t. It was an album created in the midst of global pandemic [and] a time of great suffering for society and for myself personally.”

What, When and Without sounds like Fields has had some rough times, even outside of the lockdowns (regardless of how dense the record sounds, there is a yearning in the vocals that have a certain lockdown edge); but there is also an irony in this loneliness. Megan McCormick, who co-wrote on and produced the record and plays in Fields’ band, shows great intimacy throughout the project – there is a reason for this, McCormick and Fields are personal as well as professional partners. They sound good together, and the track where McCormick sings backing vocals, “Moving Mountains,” is the highest energy, most open of the entire record. It’s a great love song – but it’s a love song which calls to Mother Maybelle Carter as an avatar of country music, as a figure outside of space and time, which can tell the narrator how to love after years of heartbreak.

When asked about McCormick, Fields is still a little coy, but her commitment to their lives and sounds is made clear: “She really has a special gift and believing in her as a producer, as well as trusting her intuitions and abilities, has allowed me to grow as an artist. She’s my toughest critic, because that’s what I’ve asked of her. She’s also my constant cheerleader. We thrive when we get to travel together and both enjoy that feeling of being untethered that you get when you’re on the road.”

One can hear some of the untethered quality in Fields’ work, the road as untethering as much as time or genre, but the closeness that she has with McCormick is another kind of tethering, be it a consensual one.

Throughout the album, there is a quality of choosing which traditions are valuable, which are worth keeping, and which ones might have outlived their usefulness. When she talks about her childhood as a Pentecostal, she says: “I am very spiritual, still, and that energy I saw in church growing up is no different than the energy I feel when I’m composing music or playing music with other people with whom I am ‘tuned in.’”

She is definitely tuned with McCormick, their close contribution seen in how they work together – the harmonies without necessarily the negative consequences of some of that church life. She continues: “Those are universal aspects of the human experience that transcend dogma, class, and denomination and that’s what I carry on and value from my experience in church.”

One can see the universal quality in Fields’ work, and it contains interesting juxtapositions. A rootlessness across genre or time, which lands on something contemporary sounding; or a heartbreak record which rests on multiple commitments to one person; or even a religious tradition which widens and deepens.

Maybe we don’t need that taxonomy. An audience knows what a country record is.

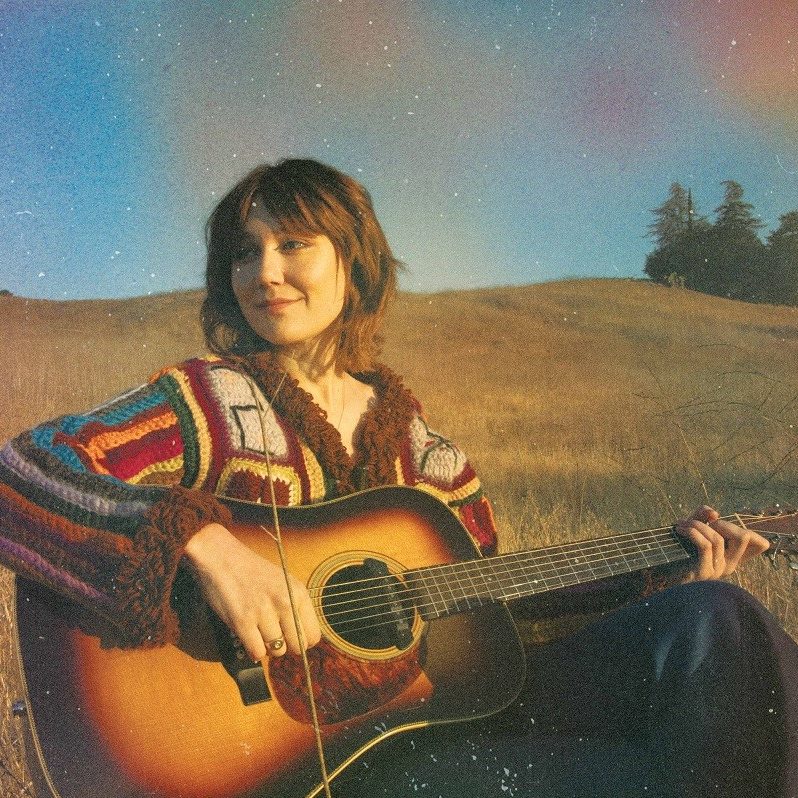

Photo Credit: John Brown