I originally didn’t want to write this column.

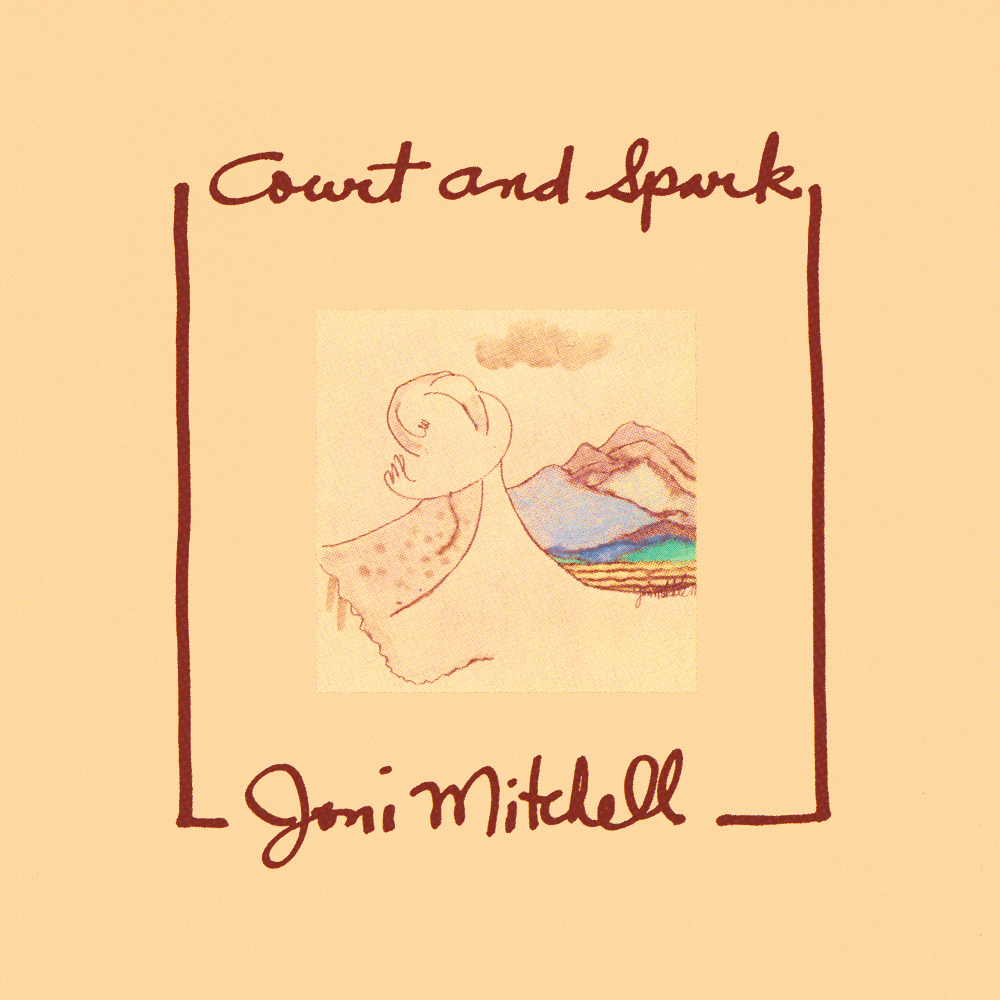

When I first asked the Bluegrass Situation’s wise and heroic editor if she had any album suggestions for the next Canon Fodder, her immediate response was: Joni Mitchell. “Maybe Court and Spark,” she recommended. I think I wrote something curt and casually dismissive back to her, something about being allergic to Joni Mitchell. And it’s true: I’ve never been a fan. At various times in my life, I’ve heard various albums by Joni, and they washed over me unnoticed just as often as they actively irked me. She was, in other words, the last person I wanted to write about.

And yet, here I am writing about Joni Mitchell.

Between that email exchange and this column you are currently reading, I became more and more intrigued by such an assignment. Why, I’ve been wondering lately, have I nursed something akin to a grudge against an artist who enjoys the respect and admiration of so many people I respect and admire? What was at the root of my disdain for such a well-regarded artist, one who has earned the label “genius” throughout her career? Is everybody else in the world wrong? Or is it me? Is there a correct answer here?

It occurs to me that every listener has a major artist they cannot abide. Not everyone can like everything they hear, and I certainly wouldn’t want to get stuck on a long road trip with someone who has no strong opinions. I’ve had heated — thoroughly enjoyable and critically rejuvenating — conversations with people who think Dylan is a terrible singer. Van is a hack. Springsteen is a goofball. Kendrick is a terrible rapper. The Beatles are boring.

Okay, that last one is me, again. But my point is this: What we don’t like is usually as essential to how we define ourselves as what we do like. That’s certainly true online, where hating the latest Star Wars is a vocation. We define ourselves against certain kinds of music, or possibly in opposition to the fans of that music — which is why many people don’t think they like country music or jam bands. I spent much of my youth doing just that: cultivating dislikes, waging personal wars against the Beatles or whomever else I deemed “overrated.” As I’ve grown older, my viewpoint has softened and I’ve developed an appreciation for what the Beatles achieved, even if I think they should be a gateway band rather than an endpoint. That’s a lot different than just shouting, “The Beatles suck!” at random passersby. It’s hopefully a more nuanced critical take on that band — although some might call it “dumb” and, honestly, I wouldn’t argue.

That’s what happens as we get older. Or, it’s what should happen. We ought to allow our tastes and opinions to grow much more complicated as we integrate more experiences and more knowledge into our identities. We don’t want to get soft or dismissive, but we also don’t want to stop growing or considering other perspectives. Perhaps that’s why I felt compelled to write about Court and Spark for this column: I wanted to see if I’ve grown up any more since the last time I listened to Joni … and, if so, how much. I’ve been curious if my perspective has changed on the album and on the artist at all. I chose this album for various reasons: It’s her commercial breakthrough, her biggest-selling album, and one that introduced a new phase in her career. Actually this record introduced the idea that her career would have phases — that she wouldn’t forever be the wallflower West Coast folkie of Ladies of the Canyon and Blue, renowned for her fragility, as well as for her lyricism. She recorded with Tom Scott and L.A. Express, a jazz fusion outfit that allowed her to dramatically rethink her songwriting — what words she chose, which stories she told, how she phrased her vocals rhythmically and melodically. Court and Spark expanded what singer/songwriters could do and how they could sound, wrestling the vague genre away from the rootsy and the folksy and creating something more urban, more modern.

As such, it’s impossible even for me to deny her influence on pop and roots music, even R&B and hip-hop. Prince gave her song “Help Me” a shout-out on “Ballad of Dorothy Parker,” and she was, perhaps, the only artist who could make him tongue-tied. Aimee Mann and Sufjan Stevens have both covered “Free Man in Paris.” Katharine McPhee covered “Help Me.” Jeff Buckley did “People’s Parties” on Live at Sin-é. And I’m not the first to argue that Taylor Swift’s entire career is based on Mitchell, specifically on her tendency to turn lovers into lover songs.

Mitchell, of course, is much more acerbic and painterly in her love songs, often writing lyrics as conversations between herself and these famous men. If Swift turns her albums into tabloids about herself, Mitchell, to her immense credit, used this tack to push against expectations of herself as a female singer/songwriter and to establish herself as an independent and individual artist. There is something powerful in how swiftly and efficiently she dispatches a lover, especially on “Help Me. “You’re a rambler and a gambler and a sweet-talking ladies’ man, and you love your lovin’ but not like you love your freedom.” As Dan Chiasson recently observed in The New Yorker, “Men often wanted Mitchell to be a wife, a muse, a siren, or a star. Instead, they got a genius, and one especially suited to deconstructing their fantasies of her.”

So I gave Court and Spark another listen. Several listens, actually. For the purposes of this experiment, I listened to the album in as many different settings as possible: I listened on headphones in the grocery store and walking the dog in the park. I played it in the car running errands. I played it on my computer while I sat at my desk. I gave it various amounts of my attention, following closely along with the lyrics, then letting my mind wander, then letting myself get distracted by the task of scooping up dog poop. And do you know what happened?

Nothing.

I experienced not great epiphany. Lightning didn’t strike me through my earbuds. I remained cold to her singing. I remained unmoved by her lyrics. I remained unconvinced by the jazz arrangements. Certain elements stuck out to me as more compelling than I remembered, in particular the mise-en-scène on “People’s Parties,” which conveys a fragmenting anomie that puts me in mind of Joan Didion. The intro to “Raised on Robbery” reminded me of the Manhattan Transfer, but I like the groove she finds, which reinforces the sexual confidence of her narrator: “I’m a pretty good cook, sitting on my groceries,” she sings, as the song bounces along. “Come up to my kitchen, I’ll show you my best recipe.”

But there were passages that gnawed at me a bit. The hook on “Free Man in Paris” sounded fussy, a garbled melody. In “The Same Situation,” there was “a pretty girl in your bathroom, checking out her sex appeal” — a phrase that ground awkwardly against my ears. And while I appreciate that she is using “Twisted,” a hit in 1952 for the British jazz singer Annie Ross, as a winking commentary on the psychoanalytical relationship between herself and her listener, the song itself is ghastly, sounding more like a parody of jazz than jazz itself.

And yet, I can’t make any of these criticisms add up to a bad album. Perhaps not liking Court and Spark is a physical phenomenon rather than a psychological or emotional reaction. Perhaps it occurs on a cellular level, the way popping bubble wrap is ecstatic or the feel of frosted glass is unnerving. Perhaps it really is something like an allergy — a physical rejection of something that might otherwise cause pleasure. Whatever it is, whatever its cause, I’m now convinced that it is my own loss.