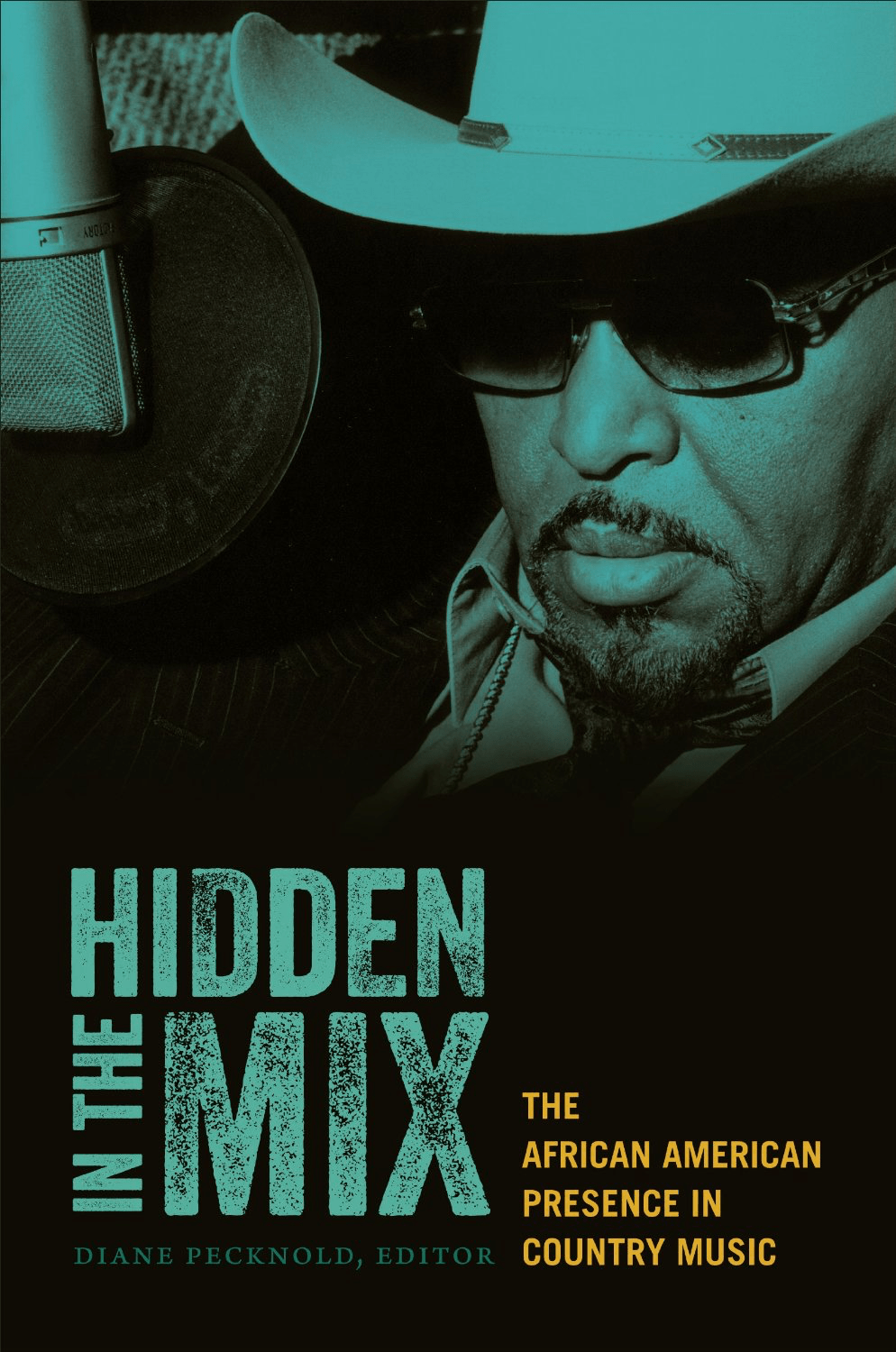

Here’s Part II of Jewly Hight's interview with Diane Pecknold, who edited and contributed to Hidden In the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music and previously authored The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry. (If you missed Part I, be sure to check it out here…)

Besides Ray Charles, you mention a number of other examples of southern soul singers recording country songs. And in Charles Hughes’s chapter, he talks about that exchange between the Muscle Shoals, Memphis and Nashville scenes and highlights African-American songwriters who could get country cuts in Nashville but couldn’t get anywhere as performers there, like Arthur Alexander.

What we’re talking about is the difference between having an existing industry infrastructure and not having one. Besides the example of Burke knowing who to get to produce his album Nashville and what material to put on it to attract a certain audience, there are other performers who are more closely identified with contemporary blues, like Shemekia Copeland and Bobby Rush, who’ve done similar things. Copeland has very deliberately drawn on Americana singer-songwriter material. And Rush consciously tweaked the sound of his new album to appeal to Americana notions of rawness and teamed up with Thirty Tigers to distribute it. I wonder if you would look at both of those as cases of African-American performers making smart, savvy use of a framework already in place.

Yeah, I think there’s a reason why Americana is a different thing from alt-country. Americana has defined itself as occupying that sort of middle ground that got lost in the genre distinctions between race and hillbilly and all of the things that followed from that. So yeah, I think, in addition to changing attitudes, there is a potential institutional home in a way that maybe there wasn’t. Although if you think about Dave Sanjek’s article on King Records, or even a place like Atlantic, people were producing both kinds of music. So to some degree, there has been some limited continuity among independent labels that have had that same mid-market niche that Americana aims at. Americana, to the degree that it’s a radio format and a genre, does provide that kind of institutional underpinning that people can take advantage of.

I like to see talented performers, who are also African-American, taking advantage of those opportunities. Not that it could even begin to make a dent in all of the lost opportunities over the years. But there is a way for performers to get themselves in front of an audience playing that music, though it is, from what I’ve seen, mostly a white audience.

Actually, I would guess that probably there is a larger African-American audience for mainstream country than there is an African-American audience for Americana.

That’s entirely possible.

And that may have something to do with the fact that artists in Americana tend to be older, tend to be performing styles that are perceived as antiquated or revivalist. You know what I mean?

Mmhmm. That brings to mind the Tony Russell chapter of your book, where he discusses why African-American musicians stopped playing the banjo. I think he does a really effective job of saying it wasn’t blackface minstrelsy that did it, but that black musicians and audiences moved on from old-time music, brought the banjo into jazz, then left it behind when they moved on to blues, since it didn’t fit the cadence, tempo or dancing style of blues. He makes the argument that black musicians were forward-looking and weren’t driven by nostalgia. Whereas nostalgia definitely seems to be something that funds revivals of old-time music. I hadn’t really considered whether the very idea of roots music or Americana, the very idea of wanting to reach back and revive something, would be unattractive and wouldn’t offer a lot of creative possibilities that they would be interested in.

Yeah. Tony’s piece to me is a really interesting one. There aren’t very many African-Americans who write about country music, but when white people write about country music, the assumption tends to be that whether it’s repulsion or exclusion, that the underrepresentation of African-Americans in country music, among artists and the audience, must be some sort of response to whiteness, or must be some sort of response to racism. And the beauty of what Tony is doing is saying, “Hey, no. This is a community of people who have their own lives and who are just interested in other things. You go on about your business. We’re doing what we’re doing. It doesn’t have anything to do with you.” [laughs] In fact, I think he would vociferously argue that he is not writing about country music even, and that he doesn’t really have any interest in it, that what he’s writing about is something else entirely, when he’s writing about old-time music. I think that’s one of the really great things about this piece is his interest in stuff that’s just, you know, separate laws of motion.

Several years ago I had a hard time finding African-American singer-songwriters to include in my book about women songwriters in Americana music. I certainly didn’t want to write only about white performers, but I needed to select artists whom it made sense to identify with Americana, taking into account how they saw what they were doing. That model of the singer-songwriter wasn’t identified with a lot of African-American performers; people have had a hard time getting away from the idea of Bob Dylan as the archetype.

So I’ve been eagerly watching what’s going on with a new generation of performers, who are songwriters and are doing stuff that I think can be seen as having a relationship to roots music, and who in many cases are African-American or multiracial, like Chastity Brown, Valerie June, or Cassie Taylor, the daughter of Otis Taylor. Do you have any thoughts on whether a new generation of performers, or even a band like the Alabama Shakes, are finding something more creatively promising, open or moldable for them in roots music, and why that would be?

Well, you know, I think it’s hard to overemphasize the importance of the idea that there really has been a significant shift in which the crossing of those racialized lines is no longer really perceived, I don’t think, to some degree, as the same sort of scandal that it once was. I think that’s part of what Adam Gussow is saying: Cowboy Troy has to highlight his crossing of that boundary in order to even make it register as a significant crossing. And I think it’s generational change over time.

And to some degree, I’m hoping that that’s what this book does also, is take away the notion that it’s somehow automatically a transgression, that it’s already always scandalous in some way. Not in the sense of racist outrage, but just sort of like, “Ooh! That’s kooky.” As we get further and further distanced from a world in which Jim Crow made every crossing of any kind of cultural or social or spatial racial line problematic, I’m sure that younger people are feeling themselves more able to do whatever they want, without having to think about the racial implications. And I think Americana and roots music, again, by emphasizing the fact that those boundaries have always been crossed, provides a space for them to do that. So you know, maybe in 10 years or whatever, the issue of whether or not there are African-Americans playing country music or African-Americans playing country-informed roots music or old-time music or whatever will just be sort of a moot point. You’d hope to get to a point where having a book like this would be sort of redundant and perplexing — like a book about left-handed people playing country music: “Who cares?” Over time I think that will happen. As you say, I think roots music is one place that makes that kind of thing possible.

Singer-songwriters are one of the most celebrated models for a performer in Americana music, especially those who write really complex lyrics or maybe have a literary bent to their songwriting. The storytelling aspect of what they do has often been celebrated more than the musical aspect of it, the singing or how it’s framed musically, what the music actually feels like. That’s certainly not what a band like the Alabama Shakes is doing. It seems to me like a lot more physical style of performance and expression. What’s your interpretation of what they’re up to?

You know, I think I heard their name first in maybe an Ann Powers review or something, and it wasn’t clear at all in the review just exactly what they were gonna sound like. So I rushed out and went and listened to a bunch of their stuff. They’re really doing something that is not country enough for me to lump it in with all of these other things that I see, but clearly also overlapping with it enough that that’s how they’re being received and perceived. To me, I feel like they are an example of a band that probably would not get a very solid hearing were it not for the category of Americana. Do you know what I mean?

Yeah.

They really do fit so much in the middle of a variety of different styles, and with the admixture of a non-revivalist attitude, I guess. … If alt-country were still a format, clearly it would never get played on alt-country. There’s too much rock in it, really, to appeal to blues revivalist types alone. I guess I just feel like they are truly such a hybrid that they would, I think, have a hard time finding a home anywhere other than through an Americana audience that had already been primed to hear all of those things and not expect or demand the dominance of any one of them.

The other thing about many of these young bands is that their take on rootsy rock has a lot higher R&B or soul quotient to it. I think it’s exciting to see them expressing themselves in a physical way, drawing on that kind of musical intelligence, bringing that into play alongside the acts that excel at writing intelligent lyrics.

I totally agree. Because of the most heavily racialized categories and the paradigm that was set up, it’s easy to always be thinking of the dichotomy between old-time/hillbilly/country and race/R&B/soul/urban as the only options, and I think that the Alabama Shakes, their performance style and their physicality, remind us there are other things out there too. And I think you can’t underestimate the impact of just plain old rock ‘n’ roll in what they do.

You said early on in our conversation that this is a book that you’re excited about putting out there. Is there anything in particular that excites you about it, or the kinds of conversations you hope it’ll contribute to?

Well, you know, one of the things I hope it sparks is this conversation that has taken place, partly around “Accidental Racist,” about whiteness and country music and how it functions. Although it’s a book about African-American engagements with country music, I assume it’s going to also [contribute to] those other conversations, in a way that maybe will create less defensiveness than the conversation that starts, “Hey, country music is only played by white people and listened to by white people.” That’s a conversation that’s really probably not gonna go anywhere, whereas I think this one has the possibility. I would like people to have the freedom to play and listen to whatever they want to play, regardless of who they are. I’d like to get to the point where Darius Rucker doesn’t have to have the conversation when he starts playing country music about “Hey, you’re a black guy. Why do you like country music?”

“Yeah, why don’t you do a show with Charley Pride?”

Exactly! Wouldn’t it be nice if he could just put out his album and people would say, “Hey, that one song is a really great song. Tell me a little about how you wrote that.” I guess I’m just hoping to have conversations about what has been possible, what hasn’t been possible, what has taken place that seemed like it might have been impossible and just further the conversation.

I think that would be a very constructive thing.

And the other thing is, I’m really looking forward to having people say, basically, “Wow, even within the constraints, there were all these people who were doing this fabulous stuff and who had an impact on this type of music that people have generally not acknowledged.

[Carolina Chocolate Drops singer] Rhiannon Giddens, somebody was again asking her, “Is it okay for a black person to play this kind of music?” She said, “You know, the music is blameless. The lyrics might be problematic, but the music itself is blameless.” And there’s a lot of great music out there, and I am really hoping that conversations develop, maybe not even a conversation that I am necessarily participating in, but that people will feel that new possibilities are open to them to enjoy things that they might otherwise not have, to recognize how awesome much of this previously unemphasized music is and to feel free to listen to whatever they want — including this music.