If you've never visited Nashville's Fisk University, it's a beautiful campus rich with history. Located north of downtown Nashville, Fisk — a private, historically Black university — was founded in 1866, just a few months after the end of the Civil War. The university was home to a number of important moments during the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century and counts Marion Barry, Diane Nash, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Ida B. Wells among its many notable alumni.

Fisk is also home to an incredible collection of visual art. While Nashville boasts art institutions like the Frist Center for the Visual Arts and Cheekwood, one of the city's most impressive collections of artwork — which includes works by Georgia O'Keeffe, Aaron Douglas, Pablo Picasso, Paul Cezanne, and many other renowned artists — is housed in a number of locations on Fisk's campus.

Rhiannon Giddens filmed her video on the Fisk campus

Jamaal B. Sheats is the Director and Curator of Fisk's art galleries, as well as an assistant professor of art at the university. A 2002 graduate of Fisk himself, Sheats has held the position of Director and Curator for 10 months and enjoys being back on campus. "It’s really an incredible experience," he says. "Every day holds a new and exciting opportunity and a new and exciting challenge. I love it. It’s interesting to come back and look at it from a different perspective. I studied the collection and, when I look at it now, I can look at a Florine Stettheimer portrait and know that it influenced my work today. It’s very rewarding, to say the least."

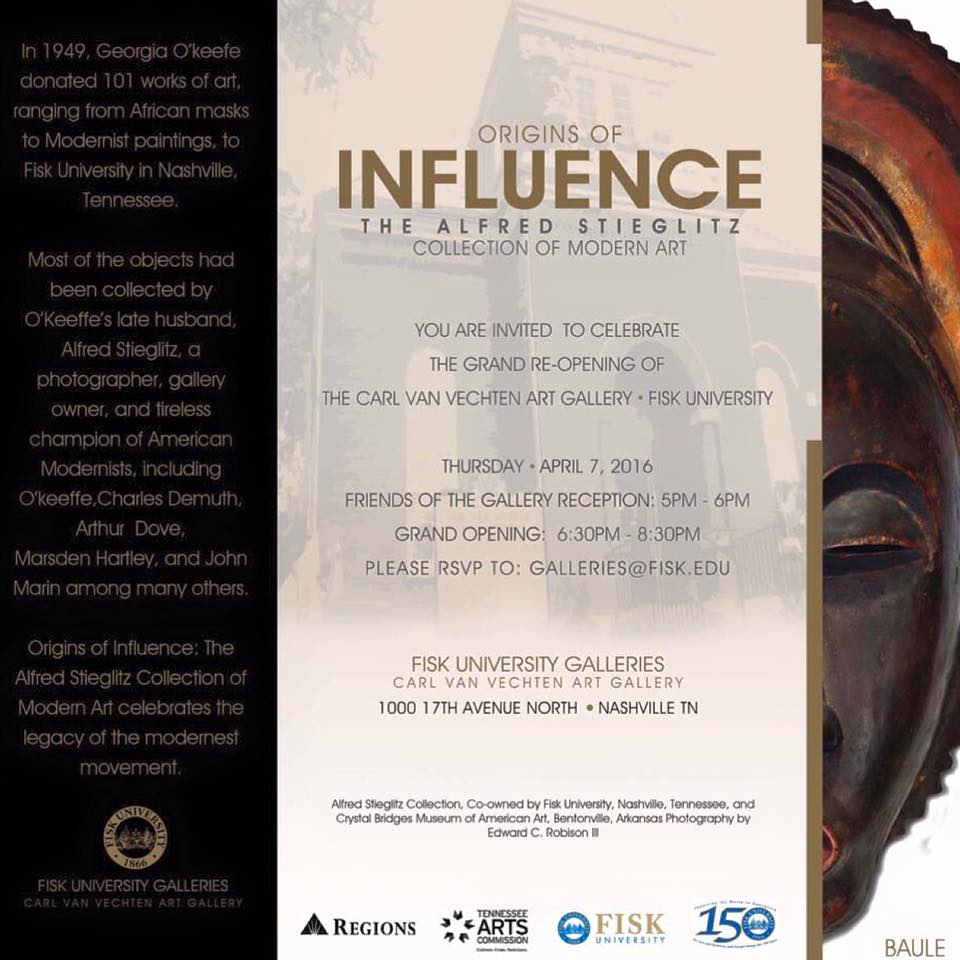

While Sheats spent his early years at Fisk studying technique — he's an artist himself, a painter and sculptor involved in Nashville's broader arts community — he now enjoys the opportunity to use Fisk's immense collection to tell important stories. "For example, we have the Alfred Stieglitz collection, that’s back. And the exhibition title is 'Orders of Influence,'" he says. "I’m looking at Alfred Stieglitz in his pioneering role as a gallery owner, a photographer, a writer, and so many other things, with his introduction of European modernism to Americans, and those European modernists, in turn, influencing our American modernists. Or Stieglitz really taking photography from documentary purposes to raising it to an art form. For Stieglitz, one of the first people to exhibit African objects in the gallery and really acknowledging that European modernists were looking at those and thinking about non-representational objects and being influenced by that work. It’s definitely a different lens than looking at it as a student."

Perhaps the most famous collection in Fisk's possession is that particular set of artwork, which was gifted to the university by Georgia O'Keeffe in 1949 in honor of Stieglitz, her husband. The collection is housed in the Carl Van Vechten Gallery, a former gymnasium that O'Keeffe hand selected when she made the donation. "It was a church, and W. E. B. Du Bois organized a group of students to purchase the building," Sheats explains. "In 1889, it became a gymnasium for calisthenics. Du Bois believed you needed to be intellectually and physically fit. Then Georgia O’ Keeffe selected the building in 1949 to become to first permanent gallery on campus."

Van Vechten, the gallery's namesake, was a famed photographer himself, with 400 of his photos as part of Fisk's permanent collection. He was a personal friend of Charles S. Johnson, a sociologist involved heavily in the Harlem Renaissance and Fisk University's first Black president, and was integral in connecting O'Keeffe to the school. "[Johnson] believed that, through the arts you could change the heart and mind of a nation," Sheats says. "He was an architect of the Harlem Renaissance. When he’s talking about art, he’s talking about visual arts, performing arts, poetry, music, literature — all of that. With that, he was good friends with Carl Van Vechten, and Carl Van Vechten is the one that made the ask to Georgia O’Keeffe. He was also instrumental in bringing Aaron Douglas to the campus to later go on and found the art department."

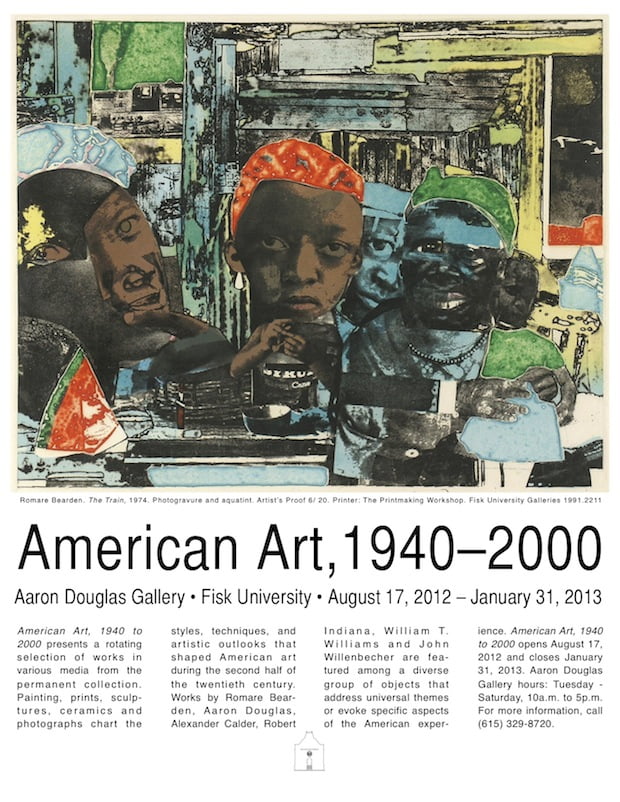

There are a number of works by Douglas, another central figure in the Harlem Renaissance, on Fisk's campus in the Aaron Douglas Gallery, established within the John Hope and Aurelia Franklin Library in 1994. The university also has vast collections of African and African-American art, including traditional African artifacts and works by artists like Hale Woodruff and James Porter. Many Fisk alumni and faculty have works in Fisk's permanent collection, as well. The university has been collecting art and artifacts since the 1870s.

The Stieglitz collection, which features Picasso, O'Keeffe, and others, remains Fisk's biggest draw, however, with the gallery notching over 2,500 visitors from 10 countries since re-opening (after a contentious two-year stint at Arkansas's Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art following a legal battle with O'Keeffe's estate) in April of this year. Sheats does not see that absence, which will recur every two years, as a detriment to his art students or to campus visitors, as the university has such a large collection outside of O'Keeffe's donation. "The Stieglitz Collection is only 101 works out of 4,000," he says. "When the collection leaves, it gives us the opportunity to show some of the other work in our collection. We have a strong foundation in African-American art. We have a strong foundation in work that was produced during the Harlem Renaissance. There was an article that came out maybe two months ago in the New York Times that talked about African-American artists marching to the museums, and they talked about Normal Rockwell, Alma Thomas, and so many others. And these are artists that are part of our collection, because there was a point in time in American history when they could only show at an institution like Fisk."

That history is, to Sheats, just as important as the technique on display in the pieces, and honoring it is at the heart of his work as both a curator and a professor. "It’s interesting because I talked about the collection from the perspective of our art majors," he explains. "But I had a faculty member ask me to pull work from two areas: the Civil Rights Movement and to look at more contemporary artists around Black Lives Matter to see what they were doing — to parallel those two periods of time. When there’s a place where there are no words, when you can’t accurately describe how you feel, I believe that art fills that void. It’s a way to tell a story when you can’t actually say the story. I think it’s very important at this time."

During a Summer of peaceful protests held in response to police violence against unarmed black men, Sheats sees art as an important tool to document the important work being done, both as a way to honor those fighting for equality and to educate generations to come. "When you talk about protest, this is something that is not just for African-Americans or for minorities," he says. "It is a perennial thing that’s happened over and over throughout history, and this is visual documentation of that."

Lede photo credit: joseph a via Source / CC BY-NC-SA