It takes about 20 minutes into a conversation, but Abraham Alexander breaks into a big grin as he looks over his shoulder around his loft in Fort Worth, Texas, and talks about his father.

“He’s been to this very place,” he says. “And we’ll play guitar together.”

And there’s the smile. It’s Field of Dreams, but with dad and son playing music rather than playing catch. And the father didn’t return from the dead, but to his son’s life from emotional distance. No wonder Alexander smiles.

Listening to the song “Heart of Gold” on Alexander’s new debut album, SEA/SONS, though, it’s hard to believe he could ever connect with his dad in any way.

And from my father’s hands

A battle rages on my skin

“It was me as a kid trying to stay strong and trying to,” he hesitates, “not black out from a beating.”

The song is just one of the affecting album’s simmering and soulful explorations of anguish both personal and societal. There are echoes of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On? and Bill Withers, a huge influence, all captured in Alexander’s gorgeous, emotive voice and spare, sensitive production, elevated by guest appearances from Mavis Staples (who adds righteous fire to the smoldering “Déjà Vu”) and Gary Clark Jr. (whose stinging guitar spikes “Stay”). The story of the album, and the story of the artist, is of shattered lives — the album opens with “Xavier,” a heartbreaking lament for his adoptive brother, who was murdered in 2017. But even more, it’s of finding hope and reconciliation. For that, music proved key.

“Heart of Gold” is a song he’s been carrying around for a long time, nearly a decade. It’s the first song he ever wrote. But it’s a memory, an emotion, he’s carried with him much longer. At age 32 now, he’s had it for more than half his life. If it’s tough for us to picture a reconciliation with his father, for him it was inconceivable.

“I never imagined it would ever happen,” he says, laughing at the mention of his smile. “And not just play guitar together, but for us to understand each other through a musical lens, and not even have to say a word, but know where each other was gonna go. Where before we didn’t even have a language that we could speak, you know? It’s…. it’s… it’s so….”

He laughs again.

“It’s wild! Even just saying this. You don’t really think about that. And you saw the smile because it was just a genuine emotion that I feel. It’s surreal that we spoke the same language. Multiple languages that we could speak, that we could understand, but yet we didn’t, we couldn’t find the words that could make us understand each other.”

There was also an image: a picture of young boys wading in the water along a beach. It’s the cover of the album.

“He looked at the album cover,” Alexander says of one of his father’s visits. “And he was weeping.”

No wonder. That image is from perhaps the last time that Alexander felt a sense of security in his childhood. The beach was in Greece, where he was born; his parents had migrated from Nigeria. The picture shows Alexander and one of his brothers playing with other boys from a tight-knit African immigrant community. It was idyllic.

“I would take my bike and there’s the Acropolis, there’s the Parthenon,” he says. “I had that freedom as a child.”

He portrays that beach scene in his song “Knee Deep,” but describes his mother being anxious and unsettled. Indeed, shortly after the photo was snapped, his parents, feeling racial animosity, applied for and won a visa lottery for entry to the U.S., with Arlington, Texas, as their destination. Alexander was 11.

The Texas air was “tense,” he says. He spoke Greek and some of his parents’ native Yoruba, while his English was limited to “hello,” “hi” and “good morning.” Just as he was starting to adapt, his life was ripped apart when his mother was killed by a drunk driver going the wrong way on the highway.

“She was my solid ground,” he says. “She was the one that really understood me, my creativity, understood the wonder that I had in my eyes. When that was gone it felt like no one really knew me anymore.”

In the song “Today” he recalls his mother, in the month before her death, telling Alexander and his two brothers that if anything happened to her they had to take care of each other. It didn’t prove that simple in the reality of her loss. His father became distant, in and out of his life, brutal when he was there. He went through a series of foster families, lost and isolated.

“I didn’t have multiple friends growing up,” he says. “My friend at school was a Power Ranger [action figure]. I would tie my Power Ranger to a bike that I took from the garbage and would ride around. It was very much me having this internal dialogue, asking questions or talking to myself. And it’s definitely played a part within my musicality. How can I say it out loud? Will people listen? Is what I’m saying even valid?”

Things turned brighter, though, when he was adopted by a couple in the church his family attended. With other kids adopted by them as well, he had a new, supportive family. The song “Blood Under the Bridge” pays tribute to this and to the bond of faith they share. Soccer, for which he showed great talent, also proved a positive force until a serious leg injury ended that.

That’s when a friend gave him a guitar and music became therapy, an outlet, but a private one for the most part. While working as a bank teller, a chance encounter led him to connect with local star Leon Bridges, which sparked him to seek out opportunities to perform. After one open-mic set, he was approached about opening a show for Ginuwine, and he was hooked.

Still, he immersed himself in work, study and activities, going back to school to become a physical therapist, on track toward a doctorate. But he also had built a community of family and friends. And they all came through for him. He’d done enough with music to get noticed a bit, and had an offer to go to London in 2017 to record.

“But at the time I was going to school, I was coaching three, four different soccer teams and I was working at the clinic,” he says. “I was probably getting 12 hours of sleep a week at this point. I would dabble in music. But they came to me and they had an intervention and they’re like, ‘Hey, you’re killing yourself and you’re burning the candle at both ends. We think that you should go with music and see what happens.’”

What happened was he went to London and in his late 20s, for the first time, made songwriting his priority. That is commemorated in the song “Stay.”

“They gave me that gift,” he says. “That’s what ‘Stay’ is all about. It’s about them. I have an opportunity to live in London, but I’m also missing my family and missing home, missing the people who make me feel alive.”

He made his first EP there, a great learning experience. When he returned, more doors opened, including chances to work with top-notch musicians and producers including Ian Barter (Amy Winehouse), Matt Pence (John Moreland, Elle King) and Brad Cook (Ani DiFranco, Nathaniel Rateliff, Hurray for the Riff Raff), who helped shape the album. He also was able to get some choice opening slots. One of those was a show with Mavis Staples in 2021.

“She spent like five minutes during her set addressing the crowd, talking about me,” he says, still disbelieving. “I was blown away. After the show I wanted to give her a hug and thank her for having me. And she’s like, ‘Baby, whatever you need, I got you.’”

He took her up on that, asking her to sing on “Déjà Vu,” inspired by the story of young Khalif Browder, who committed suicide after a wrongful three-year prison stint at Rikers Island. “Déjà vu story, same lie, another body in Glory,” Alexander wrote.

“I feel so honored that she’s on my record,” he says. “It’s as if your mother is speaking to you when she comes on. She comes on with so much ferocity.”

He first heard her recorded part while sitting with a friend in a car.

“We started weeping because of what she did with the song,” he says. “And she’s singing my words, words I wrote. But it sounds authentically her, that it came from her.”

All of this is framed with prayer. “Xavier” starts the album with a churchy organ and, after Alexander sings the first verse of mourning for his brother, a small choir of women singing “Amen,” as he pleads, “I pray I pray I pray.”

As with the violence from his father, the violence of this loss was difficult to process. When Xavier was killed, Alexander went to the scene, but was not allowed to get close to the body. There he cried.

“I wasn’t able to cry after that,” he says. “At the funeral I was just numb.”

And again, music allowed him to feel.

“I started playing the chords that you hear in ‘Xavier’ and instantly tears started to fall and I knew exactly what I wanted to say, how I felt at that time, at the scene. ‘How many times do I get carried away, like a leaf in a sea on a wave.’”

The album closes with a reprise of the “Amen” heard in “Xavier,” now carrying gratitude in Alexander’s tone as he sings “I pray” with the choir and a sacred steel guitar.

“Just a simple prayer,” he says. “Because I feel like that is a way that I can walk away, because it’s heavy. It’s very heavy and I’m bearing a lot. I want people who will honor me and listen to the record in its entirety to not walk away without being encouraged. No matter what faith they are, that they will hear this and feel uplifted and recharged and replenished and find peace, find joy and find wonder.”

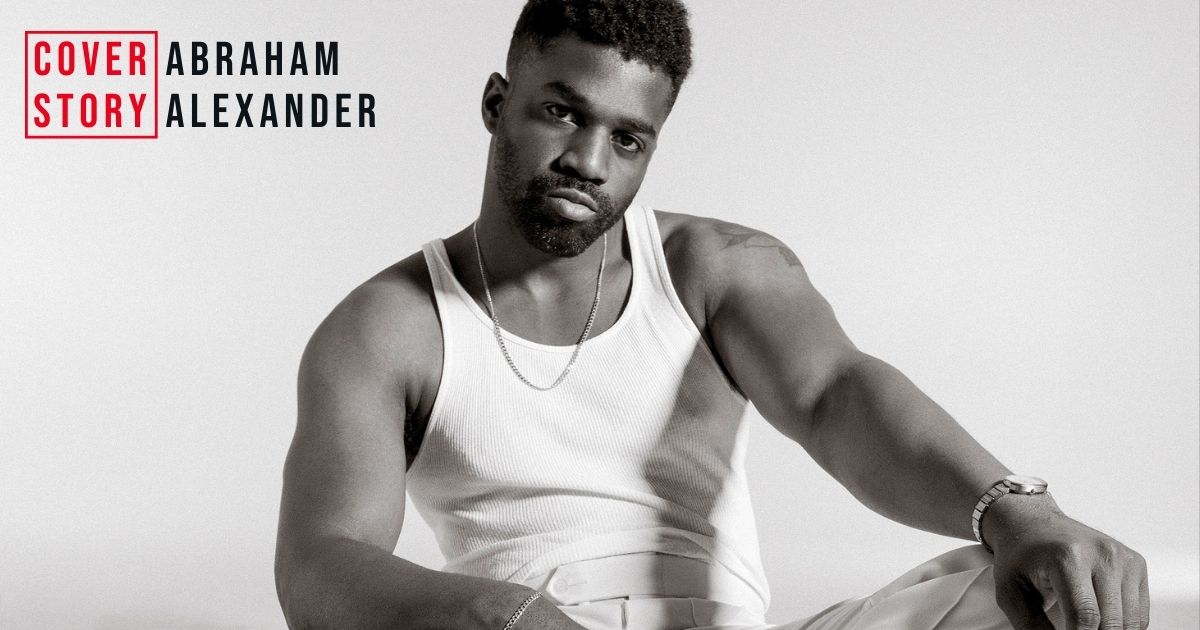

Photo Credit: Molly Dickson