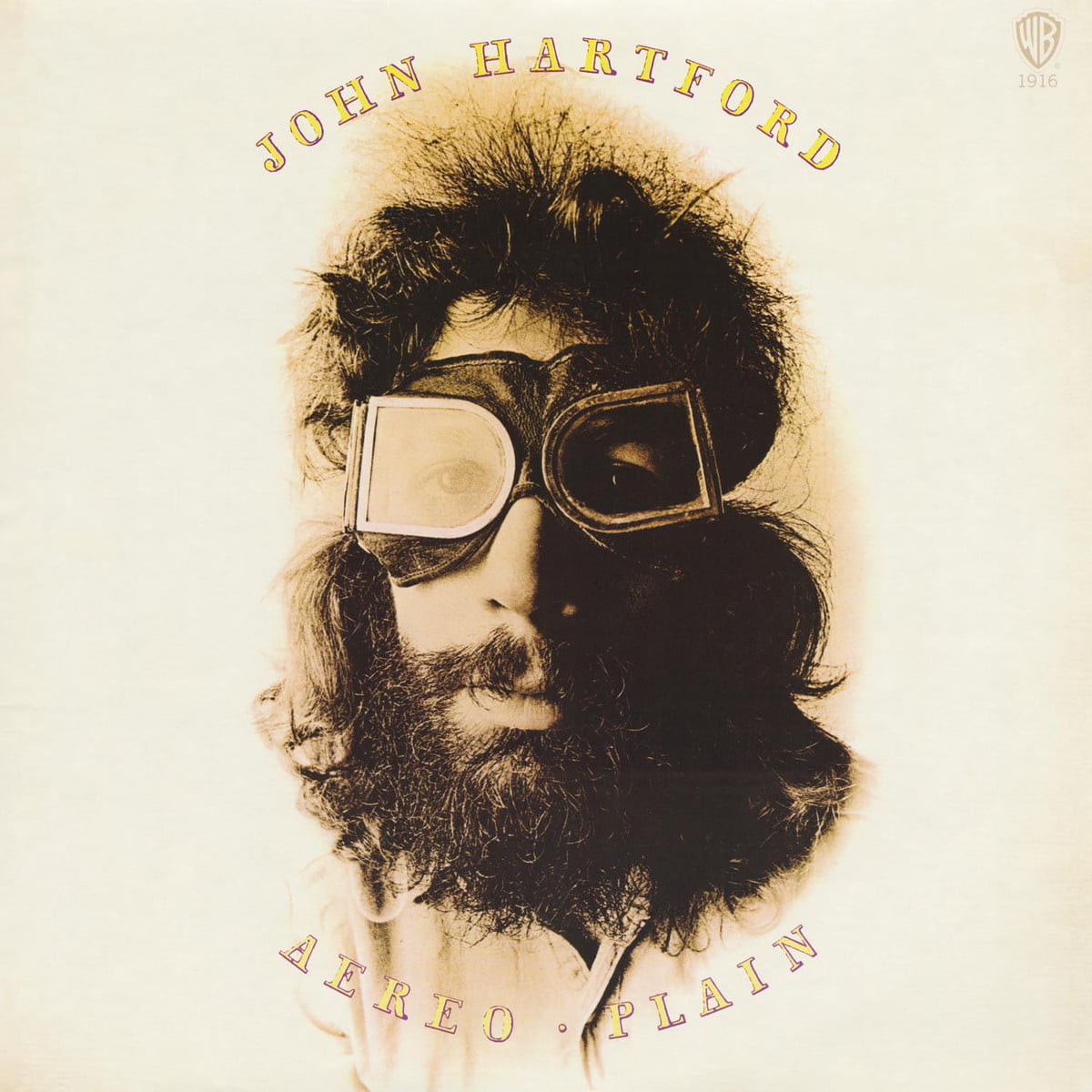

In September 2016, I did an interview with banjo player and producer Alison Brown for the now-dormant Producers column, and she told me a little bit about her studio in Nashville. Compass Records is headquartered there now, but 40 years ago, it was known as Hillbilly Central, where numerous outlaw and outlier country albums were recorded. “If I’d known John Hartford recorded Aereo Plain here, I would have been even more intimidated than I already was,” she confessed. “You could set the bar so high for yourself thinking about the other music that’s been recorded in the room, but, at the end of the day, you just have to look at it as there’s great energy in the room, great vibes in the walls, and you have to tap into that.”

I had to admit I didn’t know the album or much about the man. I knew the name, but that had more to do with the namesake music festival near my home than with any of his actual music. With minimal research, I learned that he was most famous for writing the song “Gentle on My Mind,” a late ’60s hit for Glen Campbell that was covered by everyone from Dean Martin to Aretha Franklin to R.E.M. to (most recently) Alison Krauss to (most strangely) Leonard Nimoy. I learned that Hartford was influential in the Newgrass trend of the ‘70s, and I learned that two of his songs had been included on the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack, the Big Bang of roots music in the 21st century. I learned that he was an accomplished multi-instrumentalist who clashed with celebrity of any kind. He died of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2001.

It’s always instructive to fill in these odd gaps in your musical knowledge, and the experience got me thinking about the roots canon, if there is such a thing. It’s a broad term that covers a wide range of styles and traditions and formats, from old-time field recordings to blues and gospel performances to the latest folk and country album releases to bluegrass classes in Appalachia. It’s almost impossible to connect all the dots, but it’s interesting to think about: Which record should every roots fan know about? What would a canon tell us about roots music in the 21st century? What would it say about American traditional music at a time when the entire notion of America is up for grabs?

Those questions became the foundation for this new column called Canon Fodder, so named because I like obvious puns. Each month we’ll examine a new album by an influential artist and explore its impact across generations. Hopefully this will allow us to approach some old artists in new ways, to hear familiar songs with fresh ears. If you have any nominations for albums to consider in this column, please leave them in the comments section below. I can’t promise we’ll get to each and every one of them, but I’ll definitely add it to the list.

In the meantime, it seems worthwhile to kick things off with Aereo-Plain. Brown is right: It does sound intimidatingly magnificent. There are only a few instruments on these songs, but they’re mic’d beautifully to capture the minute grain of Hartford’s banjo and the vibrations of every string on the strummed guitar. Even the goofball vocals at the end of “Boogie” — sung low and phlegmatic, as though making fun of the song that just played — are recorded lovingly and carefully, as though every mucus rumble were important. What makes the album remarkable isn’t so much the sound of the instruments, but the way they interact with one another. They’re alternately genial and hostile toward one another, supportive and undermining. The banjo plays a practical joke on the guitar; the guitar reciprocates. Especially on “Symphony Hall Rag” Hartford evokes a parallax quality in the production, with the rhythm guitar so deep in the background of the song that it sounds out of focus, which makes the song sound slightly askew.

Actually, all of Aereo-Plain sounds slightly askew … most of all Hartford himself. He comes across as something of a mad hatter on these songs — a Frank Zappa parodist for the roots set, pushing bluegrass as a countercultural force. He understands there’s power in wackiness and, even more than Pete Seeger, he believes the banjo can be a weapon against capitalism, complacency, the mainstream, the music industry, electrified instruments, or even conventional song structures. “With a Vamp in the Middle” is a meta song about itself: “I wrote this song with a vamp in the middle,” Hartford declares, but he never really gets to that vamp. He just keeps playing and singing.

If loneliness pervades these songs, it’s largely an effect of the times, an inescapable by-product of living in America during the early 1970s, when the hippie dream was curdling into something of a nightmare of violence and regress. Nixon was already a crook, but hadn’t been impeached yet. Altamont had killed the ‘60s, but the ‘70s hadn’t quite defined itself yet (at least not in America; in England, glam was already starting to define the era). Singer/songwriters like James Taylor and Cat Stevens were starting to make inroads into the mainstream, but no sound or movement defined the pop or country landscape.

Hartford sees not a land of promise or possibility, but a society gone to seed, eaten alive by progress: “It looks like an electric shaver now where the courthouse used to be,” he sings on “Steamboat Whistle Blues.” “The grass is all synthetic, and we don’t know for sure about the food.” It’s not that he wasn’t made for these times; it’s that the times aren’t made for human beings. “We’ll all sit down at the city dump and talk about the good old days,” but it’s the way he sings “city dump” that makes you think the phrase is redundant. He may decry the commodification of country & western on “Tear Down the Grand Ole Opry,” but Hartford understands that music may be our last connection to a more fulfilling past, and Hartford is content to sit down there among the refuse just pickin’ and strummin’ and singin’ and fiddlin’ while Rome burns.

These songs long for a return to the American pastoral, an escape from the pressures of progress and politics to a pre-industrial ideal and, for that reason, the album sounds alarmingly current. “Sittin’ on a 747 just a-watchin’ them clouds roll by. Can’t tell if it’s sunshine or if it’s rain, rain, rain,” he sings on the title track, his voice rising into a comical falsetto. “Rather be a-sittin’ in a deck chair high up over Kansas City on a genuine ol’ fashioned authentic steam-powered aereo plane.” It’s a dream and a mission statement — one that knows the very idea is an innocent impossibility.

Perhaps Hartford knew, or perhaps he didn’t know, that tinkerers and inventors had been trying to build such a contraption since the 1840s, when an aerial steam carriage was patented by the British inventors William Samuel Henson and John Stringfellow. Even before the Wright Brothers went airborne at Kitty Hawk, they had managed to fly a small craft on a steam engine, but they couldn’t reconcile the power of the steam with the weight of the engine. It was folly, and maybe that’s why Hartford longs for the freedom of such a fantastical vehicle. There’s power in folly, an unbridled joy in whimsy that sounds like an intense form of dissidence and defiance.