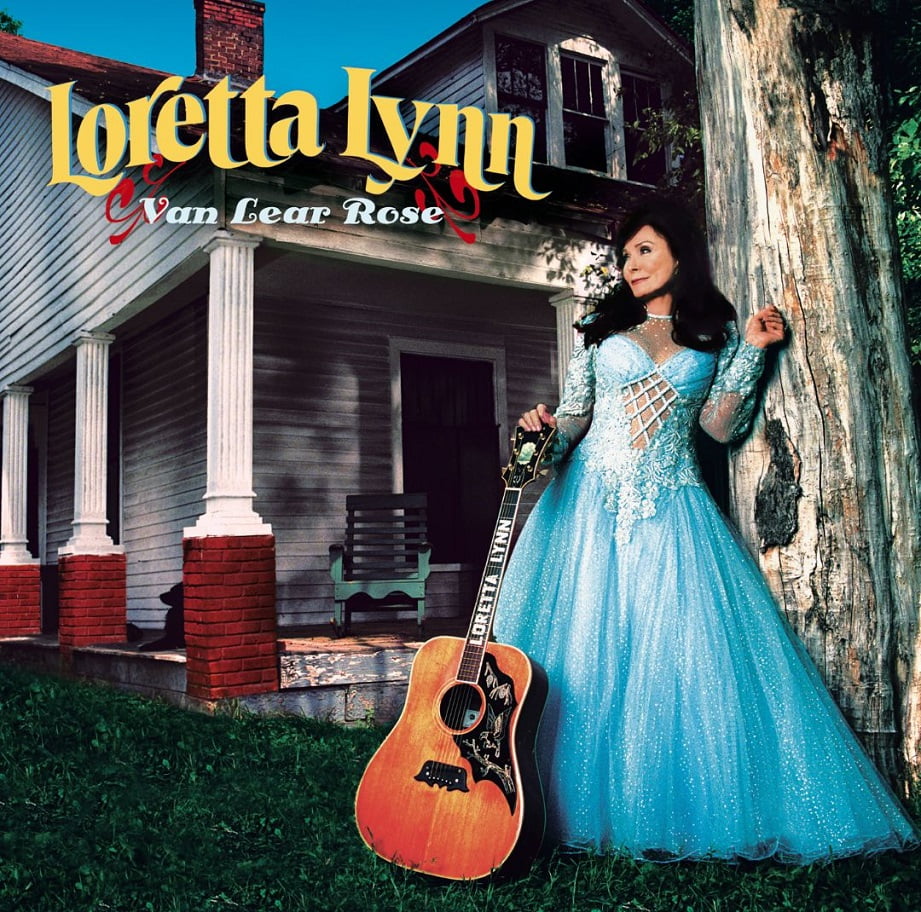

I want to tell you about one of the saddest songs I’ve heard. “Miss Being Mrs.” is a short, acoustic plaint near the end of Loretta Lynn’s 2004 blockbuster Van Lear Rose, famously produced with fanboy aplomb by Jack White. “I lie here all alone in my bed of memories,” she sings quietly, as though she had no other audience than herself. “I’m dreamin’ of your sweet kiss. Oh, how you loved me.” As White strums out a gentle and deeply sympathetic guitar theme, Lynn moves her wedding ring from her left hand to her right, confessing she misses her husband, misses the warmth of his body in the bed next to her.

Lyrically, it’s a tearjerker, with a set of lyrics as direct and as melancholy as Lynn has ever written. The predicament she describes is familiar but insoluble: something that will never change, something she must simply endure until the morning. Anyone can relate to the song, whether their partner has gone off to the great beyond or simply away on a business trip. Longtime fans, however, will easily identify the song’s subject as Oliver Lynn, better known as Doolittle or simply Doo and best known as her husband of 48 years. “Miss Being Mrs.” is a powerful bit of punctuation to their very public, very tumultuous marriage, which informed so many of her songs. The fact that she misses him so much subtly shifts the story of their marriage away from his indiscretions and underscores the many years of support and security, not to mention the large family they created together.

Mostly, though, “Miss Being Mrs.” sounds so epically sad because it’s Loretta Lynn singing it. Lyrics and backstory aside, she delivers those lines with tenacity and grace, as though she understands that her grief over Doolittle’s death in 1996 had given way to a lingering want. It’s a song about sex (a subject she never shied from addressing), about love, about security, and ultimately about the realization that all of that is gone–nothing but a memory at this point in her life. That is not necessarily a part of the song as it is written, but it is the dominant theme of the song as it is sung.

Even into her seventies, Lynn remained one of the finest vocalists ever to top the country charts, and there are so many moments that remind you what a formidable presence she is. On “Mrs. Leroy Brown” she kisses off an unfaithful husband with news of his overdrawn bank account: “”I just drawed all your money out of the bank today/ Honey, you don’t have no mo’.” It’s the way she says those last two syllables — with mock concern and very real glee — that sells the song as an empowerment anthem for wronged women everywhere. On “Story of My Life” she enumerates her sixth pregnancy with a hearty chuckle, as though she’s the gossip next door rather than the country superstar that she is.

Fan that he is, White produces Van Lear Rose to emphasize her performances over everything else. He assembles a loose band that includes members of the Cincinnati band the Greenhornes and would later record with White’s side projects the Raconteurs and the Dead Weather: Bassist Jack Lawrence and drummer Patrick Keeler prove an agile rhythm section, and of course White himself is an inventive guitarist. There are moments when that original conception of the album comes through, especially on the rockabilly rave-up “Have Mercy,” which is as much a showcase for his riffing as it is for her singing. He only sings on one song, the drunk-lovin’ story-song “Portland, Oregon,” where they play a pair of lovers who bond over pitchers of sloe gin fizz. He’s 28 and she’s 72, yet Lynn sounds like she’s about to eat him alive.

“This is gonna shake ‘em up,” Lynn would say in the studio, clutching White’s hand as they listened to a song they had just recorded together. She predicted great things for her 39th studio album, and she wasn’t wrong: It peaked at number two on the country album charts and nabbed two Grammys, including Best Country Album and Best Country Collaboration with Vocals. More than that, she knew she was doing something very different, something that her fans might not expect from her. They recorded the album in just under two weeks, recording on an eight-track recorder to keep things elemental, straightforward, “as real as possible,” White told CMT, “because that’s what Loretta Lynn is.” It was her first album of originals in decades, and it would take her more than a decade to follow it up with the underrated Full Circle in 2016 and Wouldn’t It Be Great in 2018.

Van Lear Rose did and didn’t shake ‘em up. It was Lynn’s best-selling album in decades, scoring rave reviews from publications that didn’t always cover country music. It was a bigger hit outside of Nashville than inside. It didn’t shake up the industry, but almost nothing does these days. What it did was shake up the expectations we have of older country artists. Van Lear Rose arrived exactly ten years after Johnny Cash released American Recordings, still the benchmark for late-in-life country comebacks. But each volume in that series sound grimmer and more mortally resigned than the last, such that the final albums sound like deathbed confessions. It’s a powerful series of albums, albeit a bit dreary. Lynn isn’t having any of that. She was 72 when she made Van Lear Rose, a year older than Cash when he died, yet death is barely on her mind.

Instead, her truest subject–on this and any other album she’s ever released–is life. Specifically, her own life. The coal miner’s daughter has always made hardscrabble art from her own autobiography, which nary a hint of self-pity or dread. She’s far too irrepressible a personality to let songs like “Little Red Shoes” or “Story of My Life” become grim farewells. They’re not poignant because we know they’re being sung by a woman with more years behind her than ahead. Rather, they’re poignant precisely because that’s how she sings them.