In late 2015, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist John McCutcheon received the kind of news capable of derailing any person, let alone a creative individual with lots left to say and the imagined time left to say it. Doctors found a lump in his lung and wanted to send him for a biopsy, but the discovery fell around Christmas and most services were, at best, delayed or, at worst, unavailable. McCutcheon eventually learned the lump wasn’t cancerous, as doctors initially believed, but the abscessed strep infection he did have required rest, so he cancelled the first two months of his tour in 2016 and followed doctors’ orders.

Like any storyteller who requires words to make sense of experiences and then lets those experiences out into the world as songs, McCutcheon spun his experience into music. He certainly had the time do it. “It afforded me lots of time to do writing and thinking and appreciating the fact that I get to do this amazing job,” McCutcheon says of recovering from the infection. McCutcheon gave himself over to writing and the result inevitably formed his 38th album, Trolling for Dreams. The songs encompass stories large and small, detailing everything from the epiphany he had after discovering a Bible at a garage sale to dancing with his wife in the kitchen as supper cooked on the stove. But amid those tales exist an incredibly personal tune — “This Ain’t Me.” In the song, McCutcheon details his cancer scare, describing with scalpel-like precision the way it forced him to reexamine the connection between his mind and his body. “I know people get news like this every day. Still, I gotta say, this ain’t me,” he sings in the chorus, sharing how the lump at first seemed something apart from him and eventually a part of him. It resonated in visceral ways with listeners, who saw the universality in his subjective experience. Stories, after all, exude that power.

You channeled your cancer scare into the song, “This Ain’t Me.” Has it made you appreciate music even more? That it, in some ways, gave you the form and the feeling to work through something so difficult?

Well, it’s same thing I did when I was a kid. I was working through the world, and music was a big part of it and it continues to be. Now I get to write, which is a completely cathartic experience. I never intended “This Ain’t Me” be anything but a private meditation, but I run a couple of songwriting camps, and there are good local people who have come to the camps numerous times. They have a songwriting group and they invited me one day, so I went over and they asked, “What have you been writing?” I sang them that song, and I said, “But this is just a way to write through what you’re going through.” I was trying to be the teacher. They said, “No, no. This is so universal. Remember what you taught us at camp that sometimes the most personal is unwittingly the most universal?” More than a lot of songs in recent years, when I sing that one in public, people come up to me and say, “That’s my story.”

That’s the sentiment I gathered from it. It’s something so many people deal with, but I found your articulation of the experience so compelling: This reckoning that some foreign body is a part of you, and, more than that, is hurting you.

I was pretty raw in those days. It was Christmas season; it was impossible to get a biopsy scheduled. My wife — God bless her; I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for her — she started hunting around branches of the hospital in little rural communities and that’s where we went. One of the things that may not seem quite as obvious, which is in the last verse of the song, is before they started the biopsy, they all prayed. It was the interesting juxtaposition of spirituality and science. I thought, “I’m so glad I’m in a place where there is that kind of submission to things you don’t know about,” because in some ways that’s what music is about.

All art is built on a foundation of discipline, but art is about abandon; it’s not about control. I’m doing a workshop these days called Holy Ground, which is the place where politics and spirituality meet, because that’s kind of where I came from as a kid. I think a lot of people dwell in that world, where you realize that you don’t know everything and there are things driving your life that you can’t put a finger on. To some, it’s Marxism or Ayn Rand or whatever; and to other people, it’s sort of how you grow up feeling that this is the right way to do things. And when you trace back its provenance, it probably goes back to you sitting in Sunday school or hearing your mother say something and it actually took.

It’s interesting that you say that people dwell within that space of politics and spirituality, because it strikes me how much those two concepts become almost antithetical, as you get older.

Well, I think we instinctively take big ideas to extremes, and things become really unnecessarily binary: You are liberal or conservative; you’re a Jew or Muslim. Everything is black and white.

Very either/or.

We love to think that the people in our group are deliciously diverse, are nuanced in every possible way, and the other is monolithic because we’re too lazy to get to know them. It’s one of the interesting things: The evolution of my thinking about political music. I grew up in a union movement and was really involved with the musician’s movement — still am — but I was a president of my local, which was formed to serve people in the traveling musicians world, so we got blues players, bluegrass bands, folk singers, gospel groups, and so on. I had to be involved in negotiating union contracts with presenters and festivals and stuff. I realized that I needed to know what the other side wanted, what was really important to them, so I knew what the parameters were. You’re just getting to know people. That’s the core of it. As we launch into this weird new world that seems to be so polarized, I’m not interested in playing into that anymore. I like political satire and I think humor proves that the emperor has no clothes, and here’s a guy who’s stark naked who would be really fun to write humorous, excoriating songs about, but that only plays into the disease that got us here.

That divisiveness.

Yes, we’re isolated and we’re insulated from each other. I know how to do that. I did that for a lot of years. Now, I think there’s a more creative way to move forward, and I’m interested in being part of that.

As someone who has taught songwriting, how do you keep from being too heavy-handed with a political message?

I have a number of credos that I adhere to and I teach. One of the most important is to remember that you just have the microphone, that doesn’t mean you have the answers. I remember the first time I stood up in front of a microphone, I thought, “Wow, this is an incredible privilege and, with that, comes responsibility.” Not many people get the microphone in this world, so how are you going to use it? [That development] was tempered by lots of things that happened in real life. I became a parent. What am I going to do to really parent them? Part of it is what I do with that microphone. The job of the artist is to ask interesting questions; just as important is “Don’t tell people what to do.” Give us a good idea.

How do you do that at a time when so many people seem to be shouting over one another to get their message across?

I think you can present ideas in all their messy glory. I’m interested in giving people new ideas — that’s what I’m searching for in the songs. In one respect, every song I write is a political song. You’re presenting your idea of what the world could be and, in some respects, you’re opening up the world to people. When I write songs based on my experience touring in Alaska, where I got to learn a lot about small commercial fisherman, that was opening up a world of the other to an audience that would otherwise have no experience in that.

It’s interesting that you say political, because I know the humanities continue to come under fire as being unnecessary, but I always viewed literature or music as being incredibly important because they taught empathy. And there’s a political aspect to understanding another person, another perspective.

Well, it was Kafka — and he talked about books, but substitute music, art, theatre — who said, “It is the axe for the frozen sea within us.”

I love that.

It’s beautiful. It does the best it can do, as far as creating compassion. Look, I’m a word nerd. My wife is a writer, and we have the entire 22-volume Oxford English Dictionary. I frequently go there and I look up words I feel I’ve overused or people tend to overuse, and one of the words was “compassion.” It is what every great religion, all the wisdom in literature, teaches us is a supreme virtue. I looked up “compassion,” which is really sharing in someone’s pain and, unless you are a participant, that is impossible. You’re not sharing directly in their pain. The closest you can come is empathy, and that’s one of the things that music is so powerfully able to do.

I write frequently in the first person, and I learned to do that from Woody Guthrie. “I’ll take you through a door and up a high stairs” … it’s so cinematic. Everybody in their own mind knows what that door looks like. If you ask four people, you’d get four different answers, but they were right there — they were invited in by the power of the first person and, all of a sudden, the magic can start. It was brilliant. I liberally steal from other good writers.

Well, that’s a creative trick. Or at least how you learn your craft at the beginning.

I don’t think you know that you’re doing it. I don’t think Woody would have taught a class in songwriting, saying, “Here’s how you do this.” He was just an instinctive genius, and had the ability to tell a story. And that’s what so many writers lack is the power of that connective tissue that is primal to human beings. We love stories. It’s what makes country music so popular into the 21st century. It’s the one kind of music that truly, consistently tells stories. It’s what makes Bruce Springsteen such a powerful songwriter. And it’s what drew me to folk music right away.

Is the power in the telling or is there more to it?

I’ve been a lifelong fan of the poet Pablo Neruda, and my friend took me to this place up the Pacific Coast in Chile six or seven years ago. I was walking through the courtyard and there was a boat there. The director of the Neruda Foundation said as we passed, “Oh, that’s a boat that Pablo built.” I stopped. I said, “Really? He was famously frightened of the sea.” He said, “Oh, he never put it into water and sailed it. He just built it. “ I said, “Well, then it’s not a boat.” He said, “Of course it’s a boat.” I said, “Until you put it in the water and it functions as a boat, it’s nothing more than sculpture.” And the same thing is true of the song. Until you take it out of the ivory tower of your imagination and turn it lose and let it be imbued with the meaning other people feel, then it’s just creative narcissism. I’m not an art-for-art’s-sake kind of guy. The song has to get out there; it has to do its work. And the people have to do their work on it.

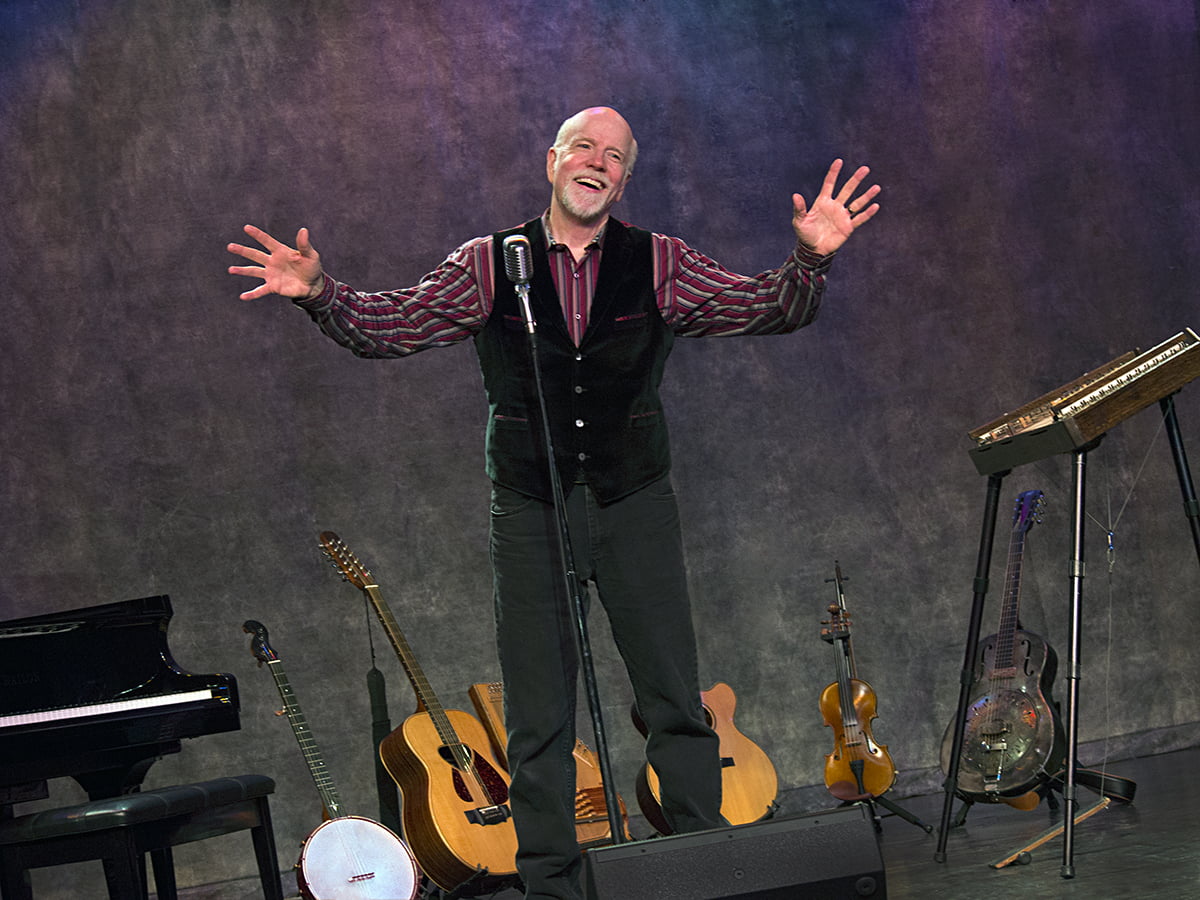

Photo credit: Irene Young