Welcome back to In Memoriam, a monthly series that chronicles Americana legends. So often, one giant is memorialized in their field while the others are displaced to historical footnotes. In Memoriam will spotlight influential musicians that are fading from the collective conscious. This month: Eddie Cochran.

At the beginning of 1960, rock ‘n' roll’s detractors appeared correct: It was a flash-in-the-pan fad. The previous year, Buddy Holly, Richie Valens, and the Big Bopper — three of the genre's biggest marquee names — died in a plane crash. Little Richard found religion. Elvis Presley cleaned up his act for a shot in Hollywood. Frank Sinatra once again topped the charts. On January 10, 1960, Eddie Cochran landed in England for a co-headlining tour with the wild man, Gene Vincent. Vincent was a waning rock star, but he could still draw a crowd. For all intents and purposes, Cochran was still on the rise.

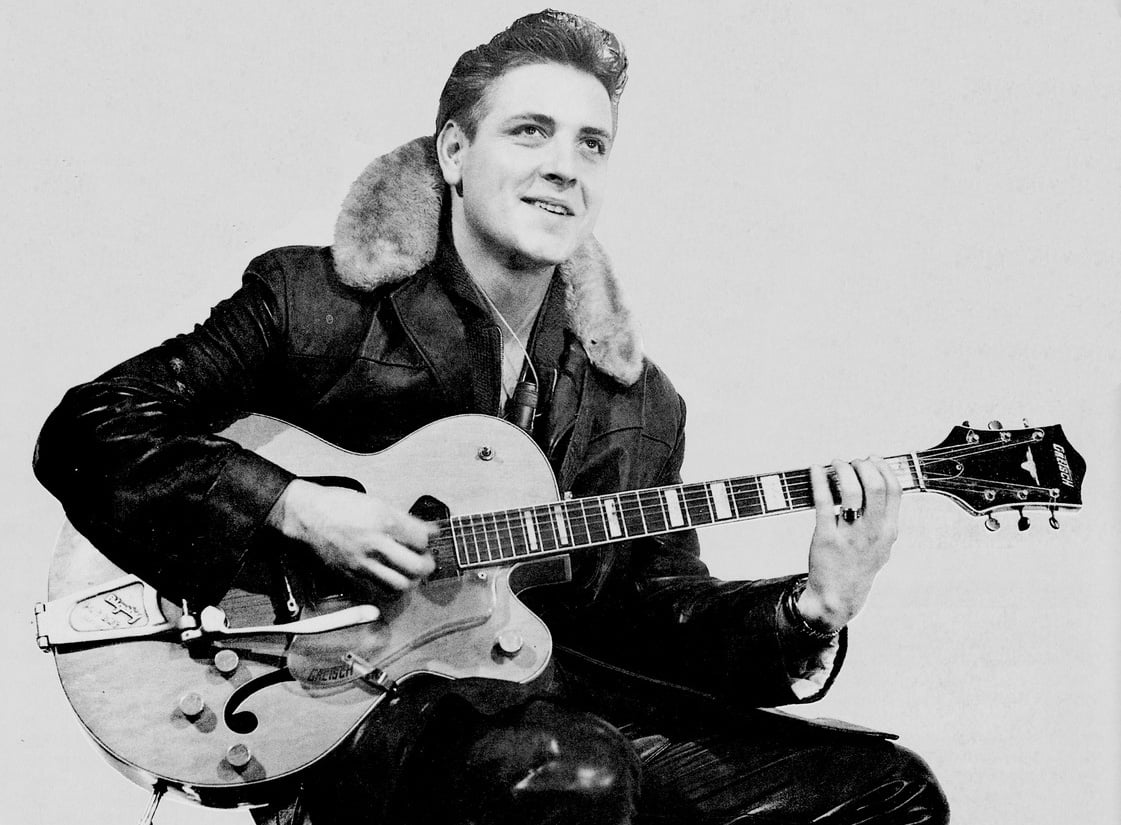

Beginning in 1957, Cochran had a handful of moderate hits that ranged from crooner teenage pop like “Sitting in the Balcony” to straight-ahead rockabilly like “Twenty Flight Rock.” In 1959, he leapt to international stardom on the polyrhythmic and acoustic guitar-driven rockers “Summertime Blues” and “C’mon Everybody.” After years as a session player, he was poised to break out as the next big thing. The tour exceeded all expectations. The English youth were hungry for rebellious music. Cochran bowled them over with his California good looks — he was blue-eyed and blond-haired. He hypnotized them with his guitar theatrics. He charmed them with his humor. Vincent also shared in the success. His black leather outfits enamored the men in the audience. England was starstruck by the Americans and treated them like royalty.

Due to popular demand, the tour was extended, and Cochran found himself increasingly homesick. “Ed was so homesick and desperate to get back. He missed his family and especially his mum. He would talk to his mum for hours on the phone and these were on their hotel bill, so I had to clear them up,” said Hal Carter, one of the tour managers. The deaths of his good friends Holly and Valens still weighed heavy on Cochran, as he feared a similar fate awaited him. Cochran, never one to shy away from a drink, began consuming as much as two fifths of whiskey a day. In later photos, he looked bloated and tired, but his performances were still top notch. Unfortunately, his heart was not in it. He finally called Sharon Sheeley, his fiancée, and implored her to join him for the remainder of the first half of their tour. She joined him at the start of April so that she could celebrate her 20th birthday with him on the April 4.

When Sheeley arrived, she found a severely depressed Cochran. By some accounts, he advanced beyond alcohol and was abusing uppers and downers. He became increasingly convinced that he was supposed to have died with Buddy Holly and Richie Valens. He visited fortune tellers, desperate to know when he would die. Soon after her arrival, Cochran asked Sheeley to go the record store and buy every Buddy Holly record. For days, he only listened to them. Sheeley finally asked, “Doesn’t it upset you hearing Buddy this way?” Cochran replied, “Oh no, because I’ll be seeing him soon.”

On April 17, the increasingly morbid and despondent Cochran was getting a break. He was flying home to Los Angeles for 10 days to fulfill a recording obligation … and for a little rest and relaxation. As the day approached, the dark cloud began to lift.

The final show before the tour hiatus was April 16 at the Bristol Hippodrome. Vincent was scheduled to perform a series of concerts in France, as Cochran and Sheeley were flying back to Los Angeles. They were all headed to Heathrow Airport, when the trains quit running early because of the Easter holiday. Johnny Gentle, the opening act, drove back to London, but his car was full. Cochran, Sheeley, and Vincent decided to take a car service. Although none of their flights were until the following day, they were itching to get on their way … especially Eddie.

George Martin was the driver of the Ford Consul and tour Manager Pat Thompkins sat in the passenger seat. Cochran, Sheeley, and Vincent were in the back with Eddie in the middle. They left for London around 11 pm. There was no major motorway between Bristol and London in 1960, so they took the old A4. According to Hal Carter, Pat Thompkins’ confidante and co-tour manager, the driver took a shortcut and ended up going the wrong way. He quickly spun around and tried to make up for lost time.

Sharon Sheeley had this to say about the fateful drive: “For the whole journey, I just sat there waiting … waiting for that car to crash. It was a very strange feeling. The minute the car door shut, it felt like I was shutting a tomb. The driver was speeding and Eddie kept telling him to slow down. I remember seeing the trees zipping by because we were going too fast, and thinking there’s nothing I can do to stop this.”

Police reports from the accident state that Martin was driving too fast. He misjudged the curve of the road and careened into a lamppost. Microseconds before the moment of impact, Cochran threw himself over Sheeley to protect her. He sacrificed his own safety to ensure her survival. She broke her neck and back, and Vincent reinjured his leg that was previously hurt in a motorcycle wreck. The front seat passengers suffered only scrapes and bruises. Cochran had massive head trauma and was rushed to the hospital. He never regained consciousness and died the following morning.

History has not been kind to Eddie Cochran. He is remembered as a footnote to the golden era of rock 'n' roll. To many, he epitomizes the one-hit wonder. It’s a shame.

Unlike most early rockabilly artists, Cochran wrote the majority of his songs. He revolutionized the genre, as a result. In his hands, it was more than sped-up blues and country. He introduced polyrhythmic beats and more complex rhythms — h wrote riffs, which was uncommon in the late '50s. Cochran was also a pioneer in the studio. Along with Les Paul, he was one of the first to experiment with multi-track recording and dubbing. He was also an astounding and prolific session player.

And Cochran was a guitar hero — he did for rock 'n' roll guitar what Chet Atkins, his hero, did for country guitar. By treating it like art and infusing it with fresh influences, he elevated it.

Perhaps Eddie Cochran’s biggest contribution was as a rock ‘n' roll ambassador to Europe. The UK youth were hungry for the music coming from the United States, but few performers left the States for their shores. It wasn’t cost effective. Cochran and Vincent were pioneers and went overseas. Because of that tour, they are still extremely popular in England. Not only did Cochran introduce the war-ravaged country to the new rebellious music, but he also sat down and taught them how to play it: He tutored their drummers on the proper beats; he showed the correct fingerings and chords to the would-be guitar slingers. His influence on the first wave of British Rockers was profound, and it is still visible today.

Although his life and recording career were short, Eddie Cochran left an indelible mark on American music. His guitar playing inspired everyone from George Harrison to Brian Setzer. Jimi Hendrix requested Cochran’s music at his funeral. It’s a shame that we can only speculate on how much more musical ground he could have broken. Eddie Cochran might not be the most popular rock ‘n' roll musician from the 1950s, but he is one of the most loved.