Outside of Detroit’s Motown Music, soul has generally tended to inhabit more southern locales. Yet in Bloomington, Indiana, on the campus of Indiana University, a group of music students discovered how their mutual passion for older grooves kindled fires in the snowiest of settings. Louisiana native Durand Jones moved north in 2012 to attend grad school at the Jacobs School of Music, where he eventually met guitarist Blake Rhein, who in turn introduced him to drummer Aaron Frazer. Their subsequent lazy Sunday hangs, which involved exchanging their favorite classic 45s and contemporary albums, quickly turned into fervid jam sessions. And, from there, Durand Jones and the Indications (with bassist Kyle Houpt and keyboardist Justin Hubler) found themselves transforming those influences into heat-soaked soul that evoked Otis Redding, at turns, and Charles Bradley, at others.

Where ‘60s soul combined gospel with R&B, the Indications gaze further and wider, integrating rock, punk, funk, and more. The result is a sound steeped in the fires that first formed soul with enough grit to hold steady alongside the rowdiest of rock bands. The slithering drum-and-bass line on “Make a Change” — the lead track off their self-titled debut album — buttresses Jones’s guttural cry, while the slow-tempo burn of “Is It Any Wonder?” allows him to show off a falsetto-whisper that calls to mind Alabama Shakes’ Brittany Howard. Jones’s voice, which has drawn comparison to the yearning cry of Lee Fields and the robust smoothness of Sam Cooke, ties the whole affair together, but it’s not a path he foresaw walking down. He intended to play his sax at IU. But finding a soul-infused groove with a group of like-minded musicians is the same as discovering heat in the snowy plains of the Midwest: Some kinds of magic just can’t be ignored.

People tend to trek south when they’re looking for soul, but you went from Louisiana to Indiana. What did you discover there?

Durand Jones: I went up there to mainly focus on classical music, but I got a job working with horn players and charting out horn parts for the Soul Revue, and that’s how I met Blake [Rhein] — my guitar player — in that class. He told me that he and Aaron were doing this together. He asked me if I wanted to join along, and I thought it was a cool way to make friends, so I said yes.

IU’s Soul Revue prides itself on training musicians to “interpret and perform” soul music. What did the process look like when you stopped interpreting and started creating your own sound?

Aaron Frazer: I think we’re always synthesizing things. In the process of creating something new, you’re drawing from the old, and not just soul music. Ideally, we listen to a lot of soul music, but also a lot of hip-hop, a lot of country. Durand has an amazing classical background steeped in jazz, too. I think, when you aim for something, if you set out to sound a specific way, oftentimes you’ll fall short, but where you fall short you wind up finding your own voice, and I think that’s what ended up happening with this record.

I know critics have touted this as part of the neo-soul movement, but there’s so much more going on, given your differing influences.

AF: I think it comes through, especially in our live shows. You can see the different influences; it’s not just a straight-up revivalist band.

How do you top your energy every night? It sounds like one helluva party.

DJ: Whenever I met these dudes back in 2012, a lot of the guys were in a band called Charlie Patton’s War, which is a rock ‘n’ roll band, and I really do think that energy comes through live. I just try to bring it every night, just try to lay it all on the line. All of us do.

What kind of instincts have you developed to help you shape the groove you manage to find on every single track?

AF: The process of creating that first album was learning how to write songs, how to arrange, learning what the difference is between how you play during a live show versus how that translates onto a recording. I think now, as we’ve been in the process of preparing our next album, I’ve seen a ton of growth in the group. We’ve focused on concepts and working on arrangements, using more vocal harmonies, but normally, I think one person will bring an idea to the table and then everyone else will help shape that.

It’s a communal table.

AF: Yeah, it’s really, really collaborative. We all have different strengths, and we all learn from each other’s strengths. I know I’m a better songwriter for it.

DJ: It’s very organic, too. It’s never forced. I really love songwriting with these dudes.

Has it grown out of that jamming relationship?

DJ: Yeah, for sure. Aaron and Blake invited me to come hang out with them on Sundays and, eventually, we just started hanging out and listening to records and drinking beers before we even started to jam. It was really cool to see what they were listening to, and how much that was influencing them. Whenever it came to us writing and jamming together, it really taught me what they wanted from me as a singer — what to sing and how to sing it. I personally think that’s how we got to know each other.

Yeah, I read that you guys listened to a lot of 45s before you pressed your own. That must’ve felt surreal.

DJ: Yeah, it was. I wasn’t really into collecting, before I met these guys, but I grew up around a lot of 45s in my grandmother’s house, and it encouraged me to dig through those old records and find some great things. It’s a really cool hobby.

Who were you listening to?

AF: We were listening to a lot of different things. For me, Darondo is an artist that really fascinated me because he put out some singles in the Bay Area, but his music never reached outside of the region. He lived his life creating music kind of for the sake of creating music. In the very last chapter of his life, one of his songs was used in a television show, and it brought his music to a much much wider audience. He was able to enjoy that success. It’s artists like that, where it’s a message in a bottle — you record it, you send it out there into the world, and maybe one day somebody finds it. Maybe they don’t. I think there’s something really seriously interesting about that. But also, musically, his stuff is amazing. He sounds like a tripped-out Al Green.

DJ: We used to have a Dropbox where we would share music that we were really digging at the time. I remember Blake sharing Sly and the Family Stone’s first album. That was something I listened to a whole bunch during that time. I remember Aaron sharing the Alabama Shakes’ first album. I listened to that a whole bunch. There was a whole lot of gospel in that Dropbox. When I first met Blake, he played me Charles Bradley. Honestly, that album got me through grad school. Any time I was having a hard day.

Right? Doesn’t it make you feel better? I miss his voice.

DJ: Man, it’s a way of life.

I know your voice has drawn comparisons to Lee Fields, but I also thought about Charles Bradley, when I first heard it. And then I couldn’t help but think of Sharon Jones. This conversation we have about modern-day soul revolves largely around those three names, in many ways, but there’s so much more taking place. Don Bryant released his debut album last year. William Bell came back and recorded at Stax. How do you hope what you’re doing widens that conversation, and maybe shines a light?

AF: I think that’s spot on. What I really like about the DJs who have been spinning at our shows, I feel like they’re conjuring spirits in a way. A lot of times at our shows, we’ll play covers that are more obscure — they’re deeper cuts — and we really like using that as a moment to help, maybe not educate, but expose crowds to music that hasn’t been performed in decades, and certainly not to audiences like the ones we’ve been playing to. So, yeah, there’s a ton of soul music outside the Daptone family, even though we are eternally grateful to what they’ve done.

It sounds like you guys are the live version of your Dropbox folder.

AF: [Laughs] Yeah, it’s a fun way to connect. For the people who do know those covers, it’s an instant connection. It’s really fun to see who in the crowd really likes when we start playing a deep cover.

Soul music, because it grew up out of gospel, has always been attached to a message. Durand, you’ve mentioned how “Make a Change” touches, in part, on the low minimum wage many have to contend with. What do you hope to share with your listeners, besides this amazing feel and groove?

DJ: For this first album, we really focused on a broad range of love, having the party — songs like “Groovy Babe” — and political and social consciousness, but I think with this next album, we really want to dig deeper into different parts of love — like platonic love, or other subjects. We’ve become really close with the low-rider community out on the west coast, so even writing tunes about cruises. There are so many things I definitely want to write about. Also just encouraging songs.

That’s so necessary, nowadays.

DJ: Yeah, for sure. Curtis Mayfield has always been a really big influence on all of this. I really love his preaching messages, personally. I feel there could be so much more of that out there.

AF: On this first record, I feel like, generally, it’s a zoom out. The message is that people are multidimensional — that life is a lot of different experiences. Sometimes you’re happy and sometimes you’re sad, and that’s okay. You don’t have to put forward this image that you see on social media all the time — this highly curated, polished version of your life. Sometimes you’re heartbroken, sometimes you’re feeling silly in love, sometimes you’re at the party, and sometimes you’re at the protest. That’s the message of this first record.

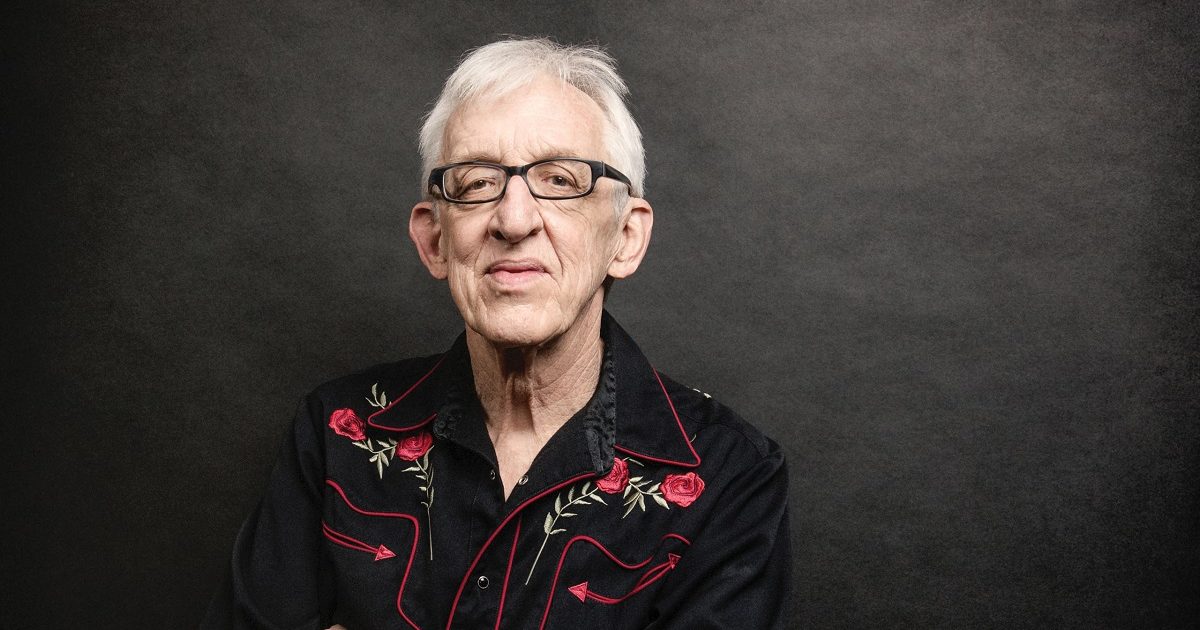

Photo credit: Horatio Baltz