Joan Baez admits there’s a gaffe in “Civil War,” a harrowing song of uprisings, both personal and public, on her new album, Whistle Down the Wind. “There are a couple of words that come out funny,” she says, “and there’s one where I sound like I have a big lisp.” It’s hard to catch that particular mispronunciation, especially as the lyrics are littered with sibilant S’s (“… this civil war”) that might blur her words together, and those mistakes may not be apparent to a casual listener or even an obsessive fan. But Baez hears them every time.

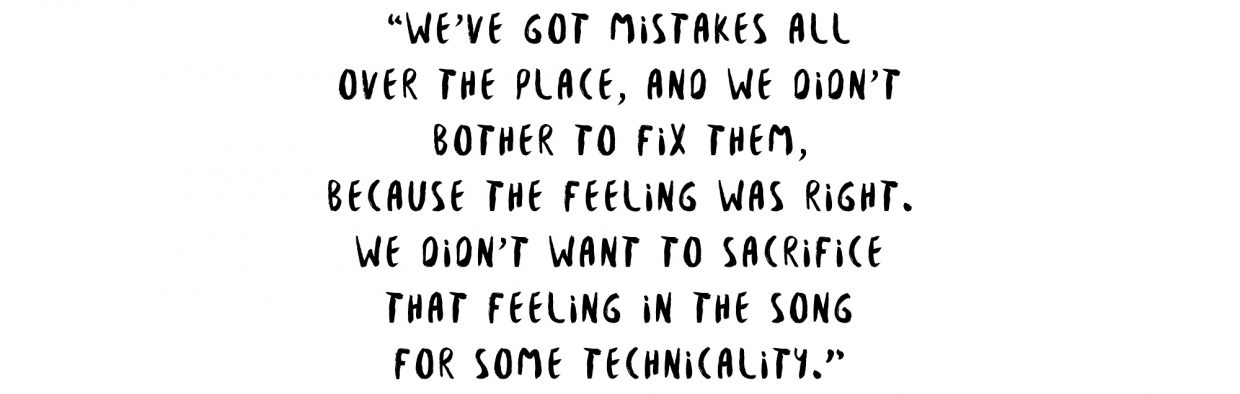

Partly, those blemishes are the byproduct of the recording process, which was loose, casual, and largely unrehearsed. Baez made the trip from her home in the Bay Area down to producer Joe Henry’s studio in Los Angeles, where she worked with a band of session musicians who have become regulars on the albums he has helmed for Solomon Burke, Lizz Wright, Bettye LaVette, and Over the Rhine. She would play a song a few times for them, enough to give them a sense of the piece and the ideas she wanted to convey. “I didn’t stop to say, ‘Listen, we’re going to hold this note for this long and do this thing here,’” says Baez. “I just didn’t know any of that. We just pieced everything together.” As a result, “We’ve got mistakes all over the place, and we didn’t bother to fix them, because the feeling was right. We didn’t want to sacrifice that feeling in the song for some technicality.”

Henry agrees, arguing that a mistake isn’t a mistake, if it actually strengthens the song: “To me, it’s only a mistake if it breaks the story and takes you out of the trance. I don’t hear that happening anywhere on the album, because people are playing together. They’re in a real-time conversation, musically speaking. They’re in a moment of discovery together, in real time. Nobody is playing anything by rote.”

Least of all Baez. Sixty years into a storied career, she is still searching, still discovering. Whistle Down the Wind is her first album in 10 years, and she has intimated that it may be her last. If so, it will be a remarkable swan song: a collection that gauges the tenor of 2018 just as intuitively and authoritatively as her self-titled debut did in 1960 or Diamonds & Rust did in 1975.

Baez speaks through the songs of other writers, bending them to the present moment or finding new implications buried in the lyrics and melodies. There are two Tom Waits character studies, odes to personal stubbornness, whose melodies and sentiments fit so well with Baez’s delivery that you’d think he wrote them specifically for her. She covers Zoe Mulford’s “The President Sang ‘Amazing Grace,’” about President Obama’s impromptu performance of an old Sacred Harp hymn at the funeral of Rev. Clementa Pinckney. Josh Ritter’s “Silver Blade” sounds like a response to the traditional ballad “Silver Dagger,” which has haunted Baez’s set lists for half-a-century.

Whistle Down the Wind is not interested in replaying old glories or indulging any nostalgia for the heyday of folk music. And that’s why those technical mistakes matter so much. Even if you don’t hear them, they nevertheless act on your subconscious. They increase the intimacy of the recording, making these songs sound more direct, more forthright, more urgent. Moreover, they speak to the messiness of what has become Baez’s truest subject: the times. Certain ideas and issues — whether it’s civil rights in the 1960s or gun control in the 2010s — are much more complicated and unwieldy than the means by which we choose to address them. It is less the fault of the song than the singer. As well intentioned and as righteous as an artist may be, the implication is that she or he remains an imperfect vessel for the song and the ideas contained within. Leaving that lisp in “Civil War” is Baez’s way of acknowledging that fact.

The miracle of her long career is that she still believes mightily that such songs are still worth singing, that they can speak to their historical moment, that music still has a function in the everyday life of a community or a nation or a planet. “It’s community building,” Baez says. “It’s empathy building.”

In the 1960s, that belief placed her at the epicenter of the folk revival, when she played demonstrations as routinely as she booked concerts. Like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, she was armed with a guitar, an encyclopedic history of folk music, and a strident sense of mission. Unlike those two influences, she had a high-flying voice, one that swooped playfully around her upper register. In recent years, age has robbed her voice of its former agility, but on Whistle Down the Wind, it has grown deeper, taking on a slightly rougher texture, yet retaining its original authority and compassion.

Her peers might have taken determined steps away from the responsibilities of protest music, but Baez simply expanded her scope and subject matter. Especially in the 1970s, she found new ways to mix the personal and the political. Never a confessional singer/songwriter — at least not in the way the West Coast folkies were — she still put a lot of herself in her songs, whether they were about her own personal relationships or those between communities. “I don’t know how I would have done that stuff back then without the music,” she says. “That was such a big part of it.”

Few folk musicians of her generation managed to keep the audience rooted in the foreground of her music. Her songs speak to “you,” but in most cases that “you” is plural. On her cover of “Another World,” by Anohni, who previously performed as Antony & the Johnsons, Baez bangs softly on the frets of her guitar, creating a gently frenzied pulse for lyrics about leaving this world and finding a new one. Her version is an ecological warning, a life-size take on a planet-size woe.

“I’m gonna miss the snow,” Baez sings. “I’m gonna miss the bees.” As the song continues, that guitar thrum becomes a timer counting down the end of a life or possibly the end of all life. “The song is as dark as it is beautiful and as beautiful as it is dark,” says Baez. “It’s spellbinding. [Anohni] turns the glass upside down. It’s not half-full or half-empty, but upside down.”

Baez changes the song in one crucial way. In her original, Anohni sings, “I’m gonna miss you all.” Baez adds a new word: “I’m gonna miss you all, everyone.” It’s a small change that doesn’t disrupt that melody or change the song in any dramatic way, but it does give an idea of the audience Baez (and Anohni) imagines for herself. She is addressing that “everyone.” “Joan understands very well that music is about community,” says Henry. “It’s about gathering people in real time to a pointed moment. It’s always and only about community for her.”

That idea is ingrained in her vast catalog, although it grows more poignant now that her career appears to be winding down. “When I go tootling around the world, I’m seeing so many different audiences,” Baez says. “I’ve played a lot of festivals in Germany and adopted France as a second country. I do five songs in French for them. I have a song for each country, or sometimes it’s just a line. It means so much to people, if you sing something to them in their own language. It’s hard work, but it’s a way to thank people for showing up.”

It’s also a way of speaking to them more clearly. In 2009, she recorded a simple YouTube clip of herself, presumably seated in her kitchen, singing a version of the old spiritual “We Shall Overcome.” It’s a song she’d sung countless times, but this version was both in English and Farsi, and she dedicated it to the people of Iran, who were protesting the contested election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. “The lyrics were written out phonetically. I couldn’t possibly remember them. And they don’t have the same scales, which meant I couldn’t get the notes right. They just didn’t exist in my vocabulary of notes.”

For Baez, music not only speaks to these communities; it binds them together and can, in some ways, define them. Every movement demands a soundtrack, and Baez is under no illusion she can provide one for March for Our Lives or Black Lives Matter or #MeToo. “We need a brilliant anthem so people have something to sing, so they don’t have to shout so much. I wish I could write that kind of thing. But it’s so hard. Still, I think it will come.”

Illustration by Zachary Johnson