Like many an artist who has given much over to their craft, Rose Cousins reached a place in 2013 where she felt overdrawn. The Canadian singer, who was born among the deep primary colors of Prince Edward Island and now lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, needed to find her creative footing again after the business side of her profession threatened to upend her spirit. So she took a break. But that break didn’t simply involve time off. It meant approaching her songwriting from a different angle.

Cousins dove headfirst into co-writing and attended several songwriting camps — in Nashville and beyond — where she partnered with artists and producers. As with a creative writing class, the assignments she fulfilled inevitably fed her more personal songwriting as she began work on what would become her new album, Natural Conclusion. It’s as though the imposed limits she experienced at those sessions — with succinct songwriting prompts that extend the mere hint of an idea — helped push her own.

Natural Conclusion blends a handful of songs from those co-writing sessions, such as “Chains” and “White Flag,” with original compositions. The album is full of space, exquisitely stitched into each lyric and musical arrangement. Cousins isn’t in a rush and allows her worldly voice to carry the weight of each struggle to its necessary conclusion. But that doesn’t mean she pushes things beyond their (forgive the tie-in) natural conclusion. “My Friend” is a short breath of a song, a palette cleanser full of meaning and recognition. “It’s short because that’s all that needed to be said,” she explains of the song’s 1:33 length. Natural Conclusion (produced by Joe Henry) offers a new turn for Cousins, who displays a beautiful, breathy vulnerability that grapples with personal, romantic, and at times even professional growth.

How does Canada’s gorgeous natural landscape get under your skin as a songwriter?

I think my inner landscape looks like Prince Edward Island. I’m definitely inspired and I feel the best when I’m near the ocean. However that might directly or indirectly transfer into my music is sometimes blatant but sometimes not. The Atlantic Ocean, of course, is my home so it’s my favorite, but anytime I can be near a body of water, for some reason it feels like it just opens my brain up. It helps me relax; it helps me feel like I’m getting a little bit of meditation.

You’ve described these new songs as containing “forward motion,” and I know you traveled a great deal these past few years. What was it about movement that helped yield these songs?

I actually think a lot of the songs are not necessarily from my travels. I think the forward motion I’m referring to is in life, in the evolution of songwriting.

And relationships?

It’s relationships, it’s the processing of things that happen in life and the sophistication of the recording process, and really feeling the forward motion in my career.

You participated in songwriting sessions during your break. What interested you about that approach as opposed to simply writing on your own?

I think my whole purpose was to get myself into situations I hadn’t been in before, and you never know what the chemistry is going to be like, when you’re in a songwriting situation with a bunch of other people. It can go any of many ways, but I think the point is like finding a partner in anything: It takes lots of practice. “Chains” was a scenario where I was paired up with a couple of people — an artist and a producer — and we were given a theme and a feel and wrote to that.

You shared the prompt on your website, and it’s almost comical in its paucity.

I think that’s what funny about most of these songwriting camps you go to: The prompts are absolutely generic. It’s hilarious. Every time you get a brief, it’s kind of like, “Slow but not too slow, sad but with an undertone of hope.” The point is, the more generic you keep it, the wider use it will have or the more people it will hit, and that is a different approach to writing than Rose Cousins, the artist, has ever taken.

It’s fun to have “Chains” on this record because, after I wrote it, I was kind of like, “Oh man, I wonder if I could sing that? I wonder if myself, as an artist, could pull that off?” and I kept that question in my mind and then decided to do a version of it. I think it’s awesome. I think it takes my stuff into a grittier moment, but also I was one of the writers on it and so I can absolutely empathize with it deeply. I was really excited about the couple of co-writes that got on here, because it is a new thing for me, and I was worried I wouldn’t be able to write something I could sing with somebody else, which I did.

Did it shift the way you write on your own?

I find I’m always patiently waiting for a song to come, and there are a few times where I’ll set aside time to be in a creative space. But it’s, ironically, the thing that doesn’t get to happen most of all in a career that’s built on making songs. So much of the touring and the motion of that is not the place where I’m creative, which is why I’m really excited about this introduction into the next chapter of having deliberate co-writing stuff scheduled in. It’s absolutely creatively inspiring and exciting because I’m going to a place to do a thing that’s actually my job. As a performer, you make an album and you go and you play that album, and then, if you get some time off, for me, maybe I’ll be able to write some songs in between. I like the addition of the co-writing thing because it kind of assures me that I will remain creative and, in fact, these last two years that I have been co-writing while gathering songs for my own record have been the most productive in the sense of increasing my catalogue.

It’s so interesting because it seems to go against this notion of, “When the muse strikes, you can’t ever know,” and “You can’t schedule creatively.”

Totally. For me — for Rose Cousins, the artist — that’s still true. If it’s going to be a song that’s coming from me and that I’m writing by myself, I can’t sit down and say, “I’m going to write a song today.” That’s never how it’s been for me. The contrast of being put together with people or organizing with people who I like to write with, or to write for an unintended purpose, or to write to have songs to be able to use as tools — which are not necessarily ones I would perform — I was able to pull a couple and put them on my record. Not thinking it would be that, it ended up feeding me, as well, in different ways

Turning to the original songs, there’s a languishing quality throughout Natural Conclusion. Not languishing as though you’re attached to the subject, but it comes across melodically and rhythmically and vocally. Was that intentional or a happy accident?

Everything is intentional and unintentional. I wasn’t like, “Let’s put more space in there.” I brought the songs as they were and the arrangements were not altered. The spaces that live in those songs were maybe accentuated by the band, who are honoring them. It’s interesting to hear you say that because I don’t listen to it in the same way or listen to those spaces. It just supports that, whether it’s melancholy or the struggle within it, the space provides some moments to digest what was just sung, or a thought that is uncomfortable in some way. I imagine that’s supporting what’s going on.

And “My Friend” is such an interesting length.

It’s like a small summary of a feeling that was a whole bunch of feelings, but since I can’t influence the way something turned out anymore, it’s like accepting it. I made a mistake, and so “my bad” and on we go. You know? Sometimes you get betrayed and it feels like shit, but you’re fine and it sucks the way that something ended up, but onward, and that’s kind of what it is. I definitely sat with it for a bit to see if there was anything more there. I sent it to Joe [Henry], and I was like, “I don’t really know. There’s something to this, but I’m not really sure.” And then we both were really excited about it at the end. It’s a random 1:30 song, but it absolutely fits.

You’re also a photographer. How does that creative medium shift the way you approach music?

I’ve been a photographer for a really long time. I used to just take photos for myself. Music is something I never used to share; I used to write my own music and never used to share it. I would do either one of them regardless of whether it was attached to my career. Photography is another interpretation of how I see the world. The same could be said for all mediums. We’re just interpreting. It’s just a visual interpretation of the way I see the world, just as songs are an interpretation of a feeling or a moment of a relationship or an experience. I love photography deeply and I’m hoping to find more ways to share more of it that I’ve done. There are polaroids I took during the recording process within [the album’s] artwork, which I’m excited about sharing. I’m a film photographer at heart, and that’s how I learned and can develop my own and print my own, which is exciting. It’s a meditative process. It’s a quiet solo journey, and I think I really enjoy spending that time kind of by myself and making things. It’s similar to music in that way. It’s a solo venture, meditative and cathartic.

You talk about doing film, which has always hit me as requiring care and consideration, unlike digital photography with its thousand storable shots and instantaneity. You have to be thoughtful about what you approach and how you approach it.

I see film photography as, every time you take a photo, you can do the things that you know — you can apply your knowledge — but you still don’t know if the photo’s going to turn out. I love that about it. I love taking that risk. I’ve developed a few films where there’s nothing on the roll and I’m like, “Ah shit. What did I do or not do?” It’s building a relationship with the camera and knowing that within any of the processes you can do all the things, but there’s still a chance that it may or may not work. The film slows you down because there are processes to make the film, to develop the film, and if you’re going to print the photos, it takes that much longer. I love the way that it slows me down.

For more conversations on creativity, read our Cover Story on Josienne Clark and Ben Walker.

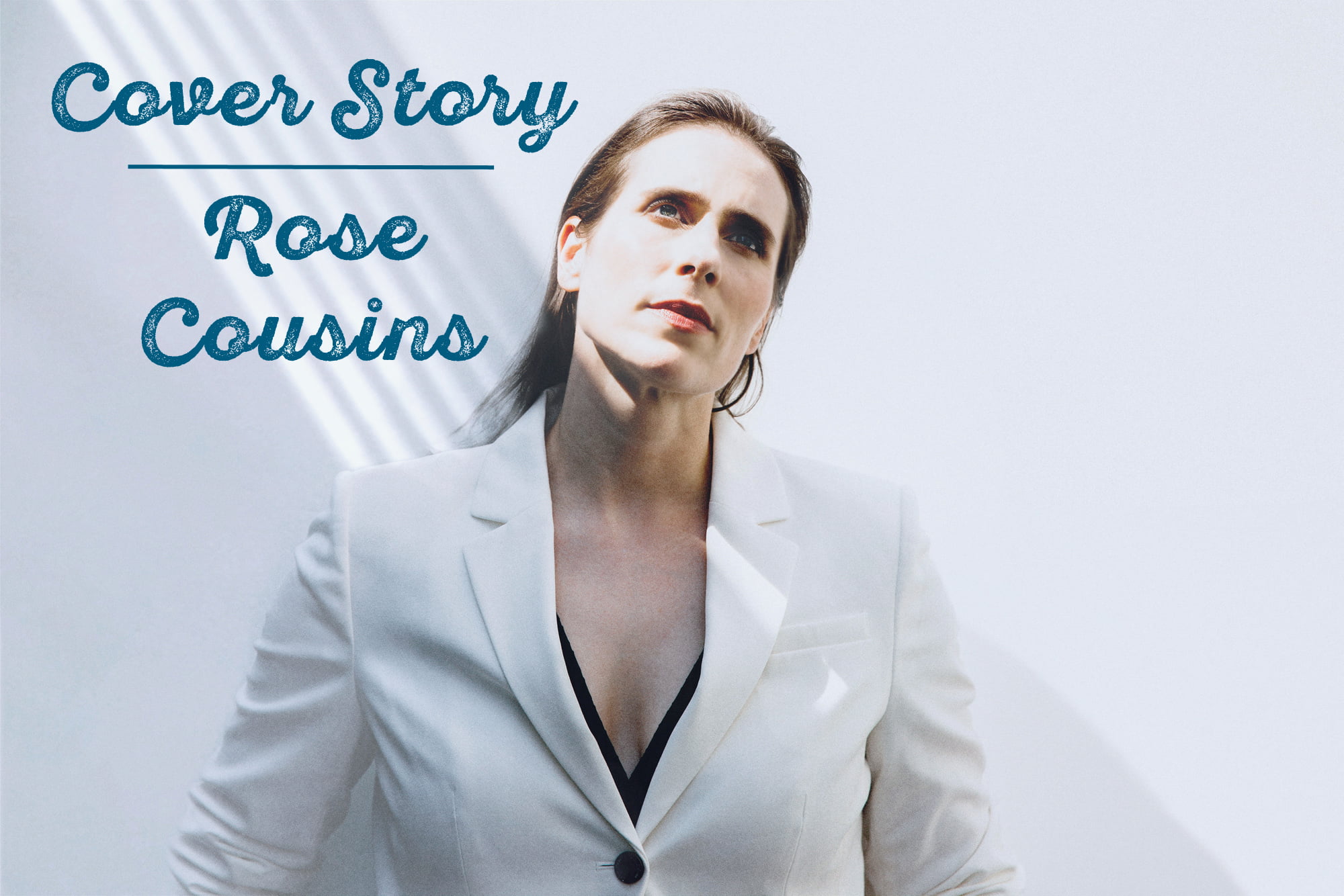

Photo credit: Vanessa Heins