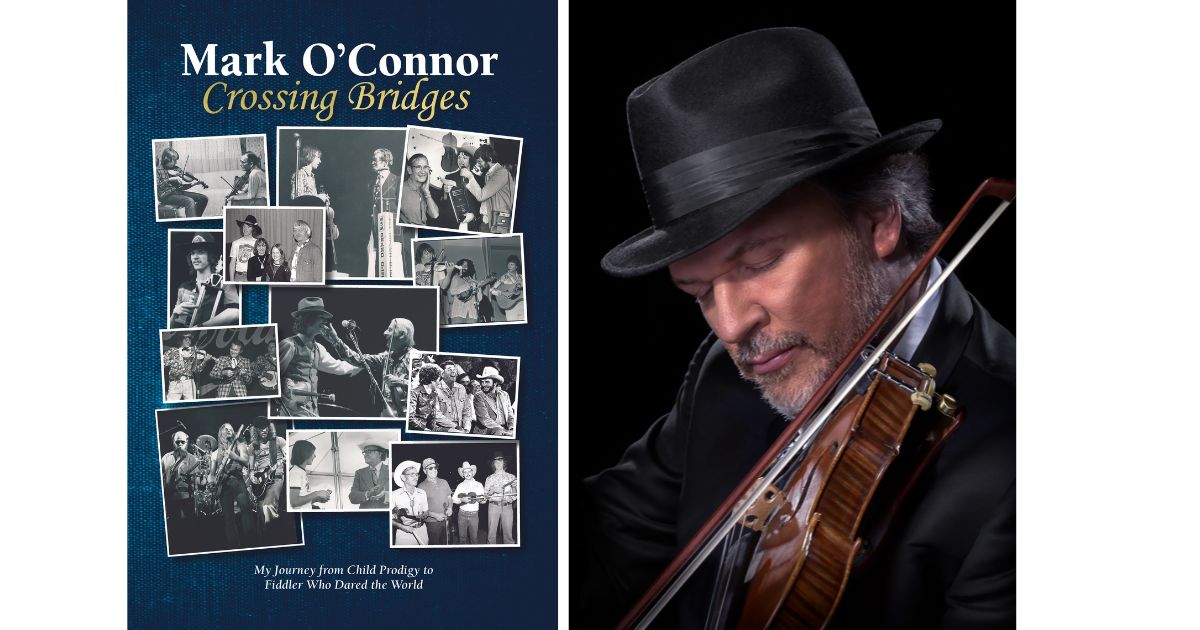

As one of the most accomplished fiddle players of his generation, Mark O’Connor could fill a book with all of his musical achievements. Instead, he goes all the way back to the beginning in Crossing Bridges: My Journey from Child Prodigy to Fiddler Who Dared the World. Retracing his seminal experiences on the stage and in the studio, the memoir concludes in the early 1980s, just as O’Connor is poised to make his mark in Nashville’s country music community.

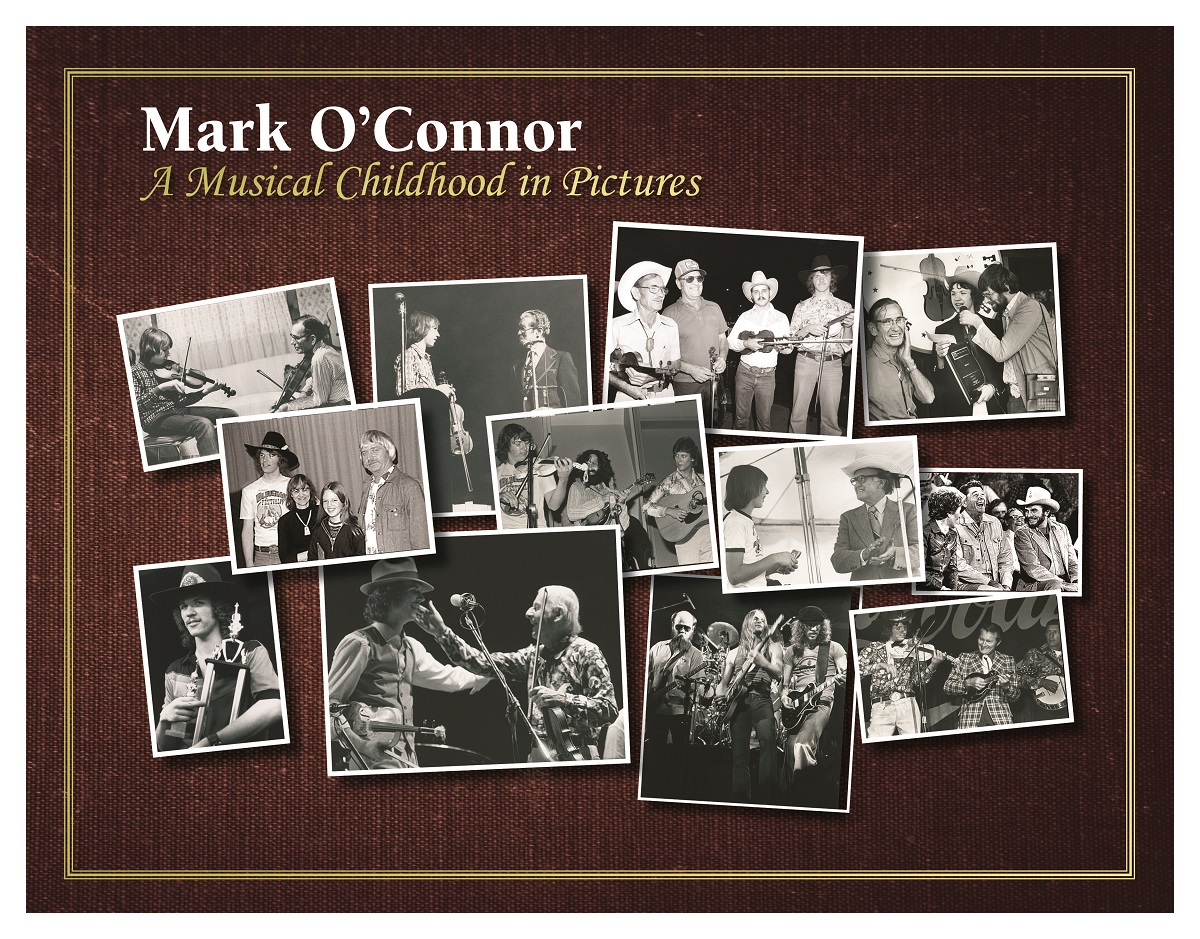

Crossing Bridges is being released on February 10, 2023, in conjunction with the CD titled Early Childhood Recordings and a collection of photos taken by his mother titled A Musical Childhood in Pictures. The Bluegrass Situation is pleased to share an excerpt from the first chapter of Crossing Bridges below.

I WAS A MERE BEGINNER BACK IN 1973, when the legendary Texas fiddler, Benny Thomasson, stopped to listen to me in the hallway of an Oregon schoolhouse as I warmed up on my tunes with an elderly blind guitarist from the area. At these local fiddle contests, Marshall Jackson enjoyed accompanying most anyone who asked. I glanced up to see Benny Thomasson coming down the long corridor, making his way toward us. I was practicing my contest round of three tunes: a hoedown, a waltz, and my tune of choice.

My first entrance in a fiddle contest was just a month earlier at the gold standard—the famed National Old-Time Fiddlers Contest in Weiser, Idaho. My instructor, Barbara Lamb, a talented 14-year-old fiddler who was also living in Seattle, was teaching me very well and charging just $4 a lesson. Barbara was preparing me for the little kids division at Weiser: the “Junior-Juniors.” This new division got going because a few youngsters in the Pacific Northwest wanted to fiddle. None of them, however, could be accomplished enough to compete against the older fiddlers. Barbara assured my mother that I could win one of the three prizes offered, but only if I practiced my rounds just as she was teaching me. Only three kids had entered the year before.

To aid in our collective effort, my mother, Marty, snuck my guitar away when I was at school. She learned to play rhythm guitar with a flat-pick all on her own, just so I could get better timing on the fiddle tunes I was learning. I was benefitting from the harmony and the counterpoint we created between the two instruments played together—a wise musical portrait to learn the violin. I could even find my pitches better when Mom added her chord changes. Mom had no experience playing instruments other than a couple years of piano lessons as a girl. She became quite good at guitar backup, even within a few weeks. Mom kept pace with me for a while, until she figured I was speeding on past her. Like lightning.

Barbara was right. At Weiser, I came out of there with a 2nd place trophy and $15. Most of all, we met a lot of wonderful people who would become our new friends in music. Folks there informed us about other Northwest fiddle contests we should go to that summer. We stumbled into a new world teeming with old-time fiddlers.

WHEN I WAS EIGHT, I saw Cajun fiddler Doug Kershaw on television: The Johnny Cash Show. That was in 1969. I was so excited by it that I begged for a fiddle for three whole years before I finally got one. My parents couldn’t afford another instrument, they always told me. Disheartened, I attempted to make a fiddle out of cardboard, using crayons to color it brown. I used more colors for the inlays. My effort folded up on me when I tried to use my guitar strings on it. By age 11, Mom finally gave in and got me a $50 fiddle from Al Sanderson, an old fiddler from Sweden we discovered lived nearby. For the next couple of weeks, I fiddled Kershaw’s “Louisiana Man” on just one string—pretty much non-stop. I played it with all four fingers, sliding up and down the neck in various positions to find the pitches. I could relate it to guitar fingering. As soon as we found a teacher, though, I started real lessons—with Barbara Lamb on October 28th, 1972. I was filled with so much joy and wonder over the fiddle.

Benny Thomasson’s favorite fiddle student in Washington state was Loretta Brank. Just one year older than me, she was winning the little kids divisions in the area handily. She repeated her 1st place standing in the Junior-Juniors at Weiser the very first year I entered. Loretta had been playing a few more years than my seven months, and it showed. Her father Kenneth, originally from North Carolina, was an old-time fiddler himself. He was responsible for making sure there was at least a little bit of prize money for his daughter and the other kiddies at Weiser. The money could provide some good incentive for those little ones to practice, he rightly expected.

Well, in a flash I was in love. Loretta was so very pretty. I did admire how good she could play at her age, too. I think I looked forward to seeing Loretta at those first summer fiddle contests more than entering them. But I thought I was too young for her, and probably not good enough on the fiddle yet. After all, she was 12, and I was still 11.

I was also going through one of the many awkward phases I faced as a child. I had a very gentle look about me, with full lips. I wore braces, too. That year, more than a few people mistook me for a girl, including some of the new kids at school. When the old-timers would approach my mother though, I cringed as they asked her, “How long has your little girl been playing the fiddle?” I had longish hair that Mom liked on me. For some quirky reason, she wanted my hair on the sides to be parted by my ears. That meant a whole chunk of hair in front of the ears. It was just so dumb looking, I thought. I argued with her about it, too, but she insisted; “Your ears should show.”

That was such a wacky thing with her, and I absolutely hated it. But I was plagued by my own wacko things, like this odd phobia, an undiagnosed paranoia called koumpounophobia—the fear of buttons. In practical terms, this meant that I would not go near anything with buttons, such as button-down shirts. The jeans had to have a snap button. So, what I wore during those years were mostly turtlenecks and pullover zipper tops. I loved those zipper tops because the turtlenecks always made my neck feel scratchy in the summer. At the time, my mother refused to allow me to wear T-shirts or sweatshirts on stage or at school. None of this helped people figure out if I was a little boy or a little girl.

I have that same button phobia even today, as I write this at 61, although it is easily manageable now. I still think about it every time I button up, though—never feeling very comfortable with the act of buttoning shirts. Despite it, I eventually learned to associate buttons with getting dressed up for musical performances—something I love to do and needed to do. I still mostly wear T-shirts when I want to feel pleasant, but as a kid anything with buttons was 100 percent a no-go.

Another remnant I carry to this day is that I never go anywhere without a handkerchief. That all started back then too. I had severe summertime hay fever in the Northwest. My Mom actually wondered if I was simply allergic to Seattle… and I may have been allergic to it, as it turns out. Just when I wanted to say something to Loretta at a fiddle contest, I usually had to sneeze and blow my nose first.

I had so many social oddities, I spent most of that whole year turning red in the face from embarrassment—triggered by most anything you could imagine. Even my ears would turn bright red, especially when they were “showing.” If someone looked my way, my entire face turned crimson, as if on cue.

I didn’t seem like the most promising child to take on a life in the entertainment field. I did wonder if I could ever get to a confidence level where I didn’t turn red.

Meanwhile, my Dad was a raging, abusive alcoholic at home—so in truth, my button aversion, my appearance, and my blushing were the least of my problems.

Times were very tough financially for my family, and we had to watch every penny. My Dad was back home working at the lumber yard while we were at those fiddle events. My mother, Marty (she much preferred this nickname over her given name, Martha), my younger sister Michelle (by three-and-a-half years) and I, slept in the back of our old, black 1959 Chevrolet station wagon. There were no motels for us. Not ever.

With the same three kids from Weiser entered in the Oregon fiddle contest, even the $10 prize for 3rd place would more than pay for the tank of gas we used coming from our Mountlake Terrace home in Seattle’s northern suburb.

There I was, warming up on my contest round of tunes Barbara had taught me. She had me playing real old-time tunes, too—hoedowns like “Boil ‘em Cabbage Down,” “Wake Up Susan,” “Cripple Creek,” “June Apple,” and “Whiskey Before Breakfast.” We coaxed her into teaching me “Jole Blon,” the first Cajun song I heard Doug Kershaw play on The Johnny Cash Show. Barbara was quite creative as a young fiddler and came up with her own version of it for me to learn. Moreover, I was particularly drawn to the blues on the fiddle. In my rounds, I played the blues tunes she taught me for my tunes of choice—“Florida Blues,” “Carroll County Blues,” “East Tennessee Blues.” Some of the older fiddlers remarked, “How did this young gal get the blues like that?” Yeah, right.

I KNEW WHAT BENNY THOMASSON looked like, though, and there was no mistaking him either. We had just seen him compete in the Open division at Weiser, and we saw him up close at a jam session one night at the Junior High “campground.” At Weiser’s main event, he was playing against several master fiddlers for the national championships, particularly a couple of previous winners, Herman Johnson and Dick Barrett. Their names were all brand new to us as we were immersing ourselves into this fiddling world. My heart skipped a beat when I saw Benny Thomasson now standing just a few feet away, listening to me. I kept my head down and played my little tunes as best I could.

At age 64, Benny was slight in stature, and at 5’ 2”, no taller than my mother. Even so, his authority was one of a granite monument. We had been listening to him a lot, both on the Weiser jam tape I recorded on our new cassette machine, and from a couple of LPs of his we picked up at the contest. I just kept playing my tunes and tried not to look up for fear of making eye contact with him. Yes, I was painfully shy.

Benny began speaking to my mother about me as I continued playing. Mom knew what a legend he was, too, and she was aware that he had recently relocated to Washington state from his native Texas. After the conclusion of the fiddle contest in Cottage Grove, Oregon that evening, my mother recounted the conversation she had with the fiddling luminary:

“How long has he been playing?” Thomasson asked my Mom.

“For eight months,” she replied.

Mr. Thomasson had only listened to me for a few minutes.

“I would like to teach him,” Thomasson said.

“We are certain we couldn’t afford your teaching fees,” my mother responded. She added, “We just started lessons with John Burke in Seattle.”

“That won’t be a problem, I’ll teach him for free,” Benny declared.

Mom saw I was growing nervous about the exchange, but she promised me that she was very gracious to him. I was thankful at least that he didn’t mistake me for a girl, like some of the old-time fiddlers did. “No, don’t worry about that,” Mom said. “We had a good conversation,” she assured me.

With the fiddler, John Burke, taking over as my principal teacher, Mom didn’t want to get too far ahead of ourselves as John was a local music celebrity in his own right. He specifically was working with me on creativity and improvisation already—how to improvise on tunes for both old-time and bluegrass music. It was, quite honestly, way over my head, but John saw a lot of potential in me for this direction. He was not at all into fiddle contests, though.

Mom was a realist, and she warned me, as her practical side materialized. “Mark, Mr. Thomasson lives way down near the Oregon border!”, she pointed out. Mom continued retelling her earlier conversation with Benny Thomasson.

“That is so very kind of you Mr. Thomasson, but we can’t really afford the gas for the three-hour drive to your home each week. Unfortunately, it is just too far away for us,” Mom determined.

She continued; “The only way we could attend this weekend’s contest is that Mark here had a good chance at the 2nd place in the Junior-Junior division, since there were only three kids entered…” Mom finished justifying her assertion.

The Texas fiddle master paused for a moment, realizing the predicament he faced against someone who, unbowed by his stature, stood her ground. So Benny Thomasson put it on the line for her:

“If you can bring him to me in Kalama, there, where I live, you see, I’ll teach the boy all day long.”

Looking back to that day, it is simply unimaginable that Benny Thomasson saw so much in me already. Although I had five years of guitar—classical, flamenco, and folk—behind me, I was only eight months into learning fiddle. I was nowhere close to the skill level of his number one pupil, the young fiddler Loretta.

Maybe Thomasson detected a potentially creative attribute in a very young student as well? To offer us this chance of a lifetime, based on his singular foresight, was extraordinary to us.

In retrospect, Benny Thomasson did have a sixth sense about me, and this proclivity would continue to play out over time.

To study regularly for long hours with one of the greatest and most iconic fiddlers in the country was beyond our wildest dreams. Even at my young age, I was able to appreciate the magnitude of it. Mom continued to talk it over with me that evening on the drive back home.

“It would require a major commitment, Mark,” she cautioned me.

“I know, I want to do this,” I assured her.

Excerpt used by permission. Lead photo by Mitch Weiss. Secondary photo by John David Pittman