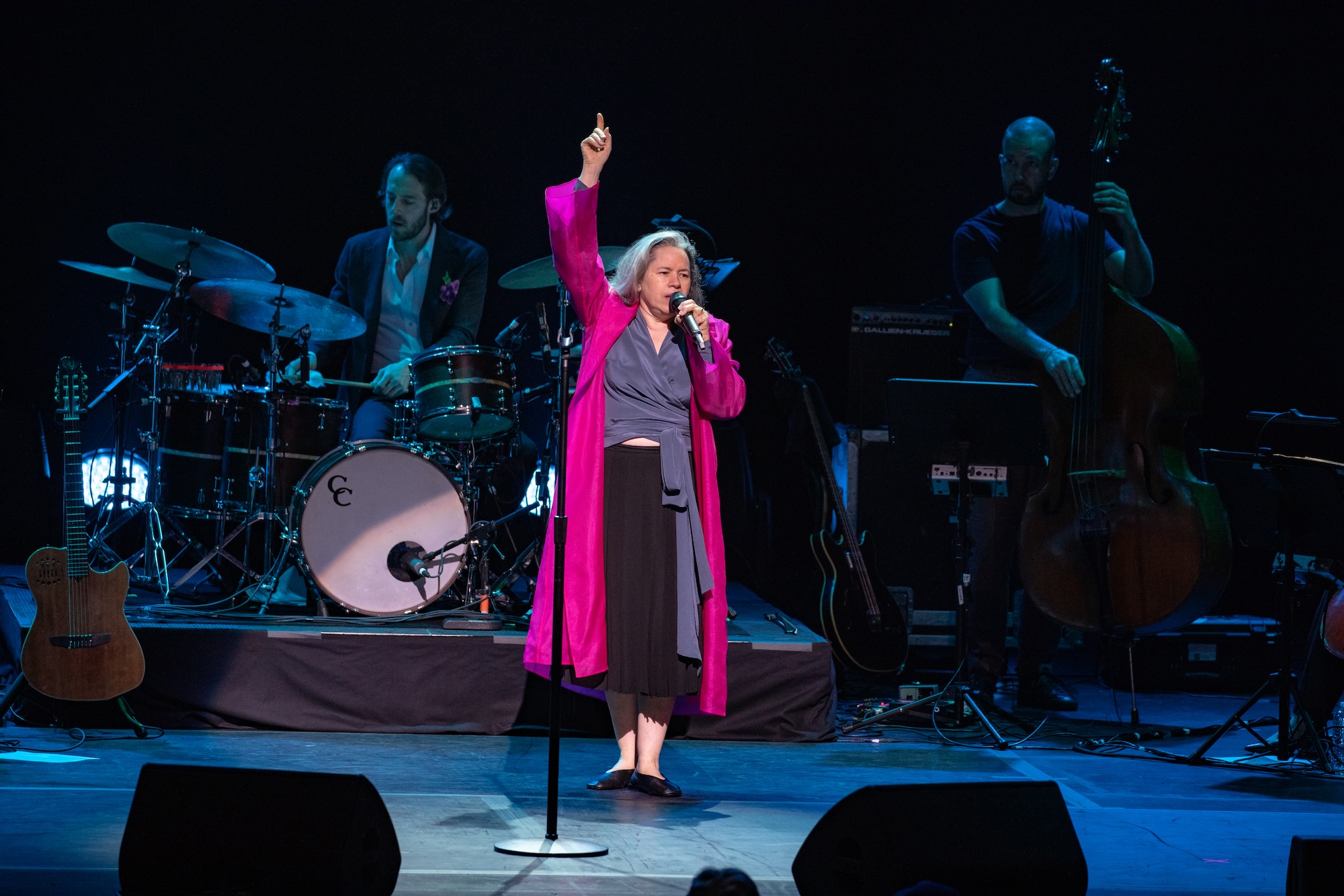

(Editor’s Note: Concert photos by David Iskra.)

From the moment Natalie Merchant gained fame as the lead singer and lyricist for 10,000 Maniacs, it was clear she was no conventional pop star — in fact, during her dozen years with that band and subsequent decades as a solo artist, she has resolutely avoided the entire notion of stardom. Merchant has instead simply followed her muse, whether it has inspired her to create music, step up as a political activist, work with underprivileged children as a Head Start volunteer, or devote herself to raising her daughter, Lucia, now 20.

Since her multiplatinum solo debut, Tigerlily, came out in 1995, Merchant has released music sparingly; her new album, Keep Your Courage, is her first collection of new material in nine years. Though she has a reputation for writing songs more focused on external issues than her own heart, on this self-produced effort she takes a deep dive into the subject of love, surveying it from multiple angles via thoughtful, engaging lyrics sung in her deftly nuanced, yet strongly sure voice. Weaving rich — yet never overdone — orchestrations around gospel-soul grooves, bits of Bourbon Street, catchy pop and sometimes Celtic-influenced balladry, Merchant crafts a sound imbued with both elegance and earthiness.

During a long, sometimes quite amusing, dialogue stimulated by her enormous intellectual curiosity and vast range of interests, it becomes clear that “elegant, yet earthy” might describe the woman as well as her art. Surprising tidbits she shared include the fact that she’s named after the late actor Natalie Wood and that she appreciated learning square-dancing in grade school. (“It was so inclusive; everybody got a chance to be someone’s partner.”) She also divulged a penchant for graphically describing the eating habits of avian predators hunting the acres surrounding her home in New York’s Hudson Valley, and confessed that, as a TV-deprived kid seeking thrills in the small upstate-New York enclave of Jamestown, she indulged in all sorts of reckless activity — including hiding near stop signs on icy roads, then leaping out to grab car bumpers and be dragged as far as possible. (“I think it gave us all character,” she says of weathering those risks, though she admits with a laugh, “If I saw my daughter doing that, I would say, ‘Look at yourself. What are you thinking?’”)

BGS: I’m so charmed by this album; the orchestrations are just beautiful. But I want to start with the Joan of Arc image on the cover; you refer to having kept it in your ephemera collection. I love the phrase, and the concept. Can you tell me more about that?

NM: Oh, my ephemera collection — I think I was 14, 13 when I started collecting junk. It’s very well organized. I’m going upstairs to look at it so I can tell you. There is an entire cabinet of glass-plate negatives; tintypes, daguerreotypes … 10 boxes of postcards, catalogs, Victorian parlor photos. I collect real-photo postcards, from the turn of the century to the 1930s; you would have your photographs made into a postcard. … Mentor (magazine) folios, advertiser cards — which I love — studio portraits, childhood images, “Museum of Mankind” — for some reason, I named that box — ethnic costumes, flowers and insects, large photographs, children’s book research, sketches … I started collecting it because I lived in a small town where there wasn’t that much to do. I basically wanted to create my own little museum in a box, so I did. [Laughs] When 10,000 Maniacs started making records and having to make posters and all that, I was responsible for doing a lot of the design work, and I would use my ephemera collection.

That leads to the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center and your appointment to the Board of Trustees. I understand that you’re passionate about making the archives more accessible for research and education. Can you tell me a bit about how you regard those archives and what you’d like to see happen with them?

Well, my appointment happened at the end of November and had to be passed by Congress, so I didn’t get official word that I could be in the building with credentials until Christmas. I went down in early January just to meet the staff and have a tour, then went back a few weeks later because I was so excited. It’s awe-inspiring. They have millions of articles and artifacts, and it’s not just folk music. For instance, they’re in charge of the AIDS Memorial Quilt and all the objects that were donated with the quilt.

When I first heard of the appointment, all I thought [was] it was the Lomaxes, because that’s what I’m familiar with. I did a little research of my own when I was down there last time, just to see how the archive works, and just to be holding the field notes of John Lomax and see the equipment that they recorded with, and they had a card catalog – I love card catalogs! The quote from one of the people on the staff was, “We’re not just about banjos and quilts.”

Your song “Sister Tilly” is an accounting of a time in history and women who created it; that’s folklife.

I found a website that had all sorts of feminist posters from the 1970s of International Women’s Day rallies and things like that. That’s folklife — it certainly is.

And your little museum in a box; man, you were destined for this.

If I hadn’t been a musician, I would have been a librarian or teacher, or a historian.

Your bio contains the statement, “For the most part, this is an album about the human heart,” and you reference both Aphrodite and Narcissus, two ends of the spectrum. You’re beckoning the goddess of love on one hand and singing about the ultimate rejection on the other. Care to elaborate about those choices?

Well, the album’s about love in so many different forms, whether it’s platonic or romantic, or love for a family member. Or in the case of “Sister Tilly,” it’s expressing love and gratitude toward an entire generation of women — my mother’s generation, who transformed our society; women who came of age in the mid- to late ‘60s and up to the mid ‘70s. I really consider those women responsible for making the society that we took for granted.

And in the romantic love column, there’s the ecstasy of falling in love or wanting to fall in love, or invoking the goddess to bring love into my life. And then, in “Big Girls,” I say love can be deceiving and harmful, but [it’s] also encouraging people who’ve been injured in love, both in “Big Girls” and “The Feast of Saint Valentine,” to persevere, to keep their courage, to keep moving forward. The worst thing that can happen is your feelings get hurt. And the best thing that can happen is that even if you’re injured in love, there’s opportunities to grow. I think most of us will admit the most difficult things we faced in our lives were the experiences that made us grow the most.

Let’s talk about another literary figure in your life, Walt Whitman (the subject of “Song of Himself”). When did you fall in love with him?

Uncle Walt. Maybe 20 years ago. I wanted to write about Walt Whitman because I found a lot of solace in his poetry during the recent times of unrest in our country. He had such an expansive, radical love. All inclusive. In a time when people were really limiting the people who were worthy of loving. And he believed in equality — for women, Native Americans, enslaved people, just everyone. And when he went to Washington — he spent three years in Washington — he originally went because his brother was in a hospital in Washington, but he ended up staying. He got a job working as a clerk, and every day, he would go after work and spend time with the soldiers. He didn’t discriminate between Confederate or Union soldiers. They were just injured young men, or dying young men, oftentimes. He would write letters home for them, as they were dying and after they died, to tell their parents what fine, fine men they were.

He saw the humanity, not the side of the argument they were on.

Yeah. And when you’re sitting at the bedside of a 15-year-old farm boy from rural Alabama, I don’t think he understood why he was fighting anyway, other than it got to a point where you were fighting to defend your own family. I don’t think there was a lot of ideology involved in the farm boys from villages all over the North and South.

The funny thing is, Walt Whitman being a great American literary figure, our greatest poet, I wanted [the song] to sound very American. But I tried putting fiddle on it three times, I tried putting banjo on it, and it just wanted to be a song about guitar and piano. I just couldn’t fit those other instruments in. Then it occurred to me that Walt was more of a sitting-in-the-parlor-with-the-parlor-piano [type], and he also loved opera; he went to the opera all time, so I thought, this is probably more representative of him anyway.

How does “Hunting the Wren” fit in?

To me, “Hunting the Wren” is loveless love. That was written by an Irishman named Ian Lynch, who’s in a band called Lankum. I thought it was a traditional song, but when I found out that he had written it, I found an interview with him. The wren is just a metaphor for these outcast women who “flock ’round the soldiers in their jackets so red for barrack room favors, pennies and bread,” and I wanted to know the story behind this brutally simple description of prostitution, the redcoats — obviously, the British — and barracks. What I found out from his interview, it was about a group of women who lived in the most abject poverty and privation you can imagine. The local authorities wouldn’t even let them construct shelters. They lived on the outside of these British barracks, on an open plain called the Curragh, and they would dig holes in the ground and cover them with rags and sticks, to live in. They would go into the village to get food and they would be spat on and beaten. Most of these women had lost their families in the famine. Some were common-law wives of the soldiers, but they weren’t allowed to live in the barracks, and some were prostitutes. The act of sex can be called lovemaking, but if it’s bought and sold, then there’s the loveless love.

So this is an actual story.

This is Irish history. There’s an amazing account that was written by Charles Dickens. The thing that Dickens points out is they had this mutual protection for each other. Some of the women were old, just homeless women; they had different generations. The older women would take care of the children while the other women went to get food or make money in any way they could. They lived like this, I think, 50 years. It was that or the workhouse, and in the workhouse, there was a good chance you would die of disease or be raped or destroyed by working. It was forced labor. It’s pretty grim, but I really was moved by the song and I wanted to include it. And it wasn’t like I was setting out to write a song cycle about the human heart. But when I was writing the liner notes, that’s when it occurred to me that I had written these songs that had some very close connections, and then some very distant connections, but they were there, and it fit in.

Photo Credit: David Iskra