Sam Bush is well-known for his innovative style, virtuosic playing, and exciting performances that have made him pivotal to bluegrass music. Yet he is quick to point to John Hartford as the pioneer of so-called newgrass. Bush has covered many of Hartford’s songs throughout his career (such as New Grass Revival’s rendition of “Vamp in the Middle” or the legendary “Steam Powered Aereo Plane”), and during our conversation I learned that both Hartford’s influence and the friendship they shared was much deeper than I knew.

Bush’s new album, Radio John: The Songs of John Hartford (released on Smithsonian Folkways), is not only a musical love letter but a peek into the relationship between two of bluegrass music’s biggest innovators. The track listing seeks to highlight Hartford as not only a brilliant, if not esoteric, songwriter but also as a creative composer, a humorist, and talented banjo player who approached music and life with a sense of wonder and whimsy. What’s not contained in the covers can be found in the one original song, “Radio John,” which weaves many of the facets of Hartford’s life into lyrics. By playing nearly every instrument on the album himself, Bush has created a loving tribute to a dear friend.

BGS: Looking back at your careers through the lens of history, I’ve always thought of you two as contemporaries who were kind of shaping music together. But reading your liner notes, I realized how much John influenced you. In what ways do you think John’s music influenced yours?

Sam Bush: That’s happened a lot to me over the years where I’ve been fortunate to get to meet some of my heroes and then end up playing with them and becoming pals that way. John was totally influential on me and the New Grass Revival. I grew up north of Nashville outside Bowling Green, Kentucky. We got Nashville television stations out on the farm (when my dad would climb up on the roof and adjust the antennas). At the time, I didn’t realize what a fortunate situation it was that I got to watch all these great players and singers on TV. Living close to Nashville I never realized until I got out and started traveling for a living that friends of mine around the country hadn’t seen these country TV shows like I had.

I was watching The Wilburn Brothers Show one day when this guy came on singing, playing Earl Scruggs-style rolls on the banjo while he was singing. I’d never seen anybody do that. My first thought was, “Why don’t you get a guitar?” But then later to find out, well, he is a great guitar player. I didn’t catch his name. But my dad and I, within a few weeks, went to Nashville and were in the Ernest Tubb Record Shop, and I found an album called Earthwords & Music by John Hartford. I looked at that picture on the cover and said, “That’s the guy. That’s the guy I saw.”

And so I brought it home and that album included “Gentle on My Mind” and a couple of others that actually are on this record. What it was that drew me to John was the banjo picking. But once I got the record, it was the way he wrote songs. Then I was struck by hearing John play along with a rhythm section of drums and electric bass and piano and maybe orchestration right off the bat. If you listen to the way I make records to this day, I will sometimes use electric bass, a drummer, and I enjoy the rhythm section mix of the bluegrass instruments. In that way, John was one of the first performers I might have heard mixing up bluegrass instruments with drums and electric bass. I mean, Flatt & Scruggs did that later on in the ‘60s.

It’s only in the last few years, like 10 years, maybe 20 years, that I’ve really started paying attention to lyrics and songs. I started as an instrumentalist, so I sang a lot of choruses and learned the words so I could sing along. But even back then I could tell John’s songs were different. They were the ones whose words I did pay attention to. Back then, John’s main direction was songwriting and singing. The RCA records were very influential in that they weren’t bluegrass at all. His progressiveness was really attractive to me.

It makes a lot of sense that there wouldn’t have been anything at that point in time that sounded anything like that.

No, because he was putting out records like this even before the Dillards made Wheatstraw Suite. I became a big fan of his. I would pay attention and see him pop up on The Smothers Brothers Show and later learned that he was one of the comedy writers. Of course, we got to see him on Glen Campbell’s show. They’d have a little acoustic picking segment in each of Glen’s shows and that was really fun for me. I bet there’s a video on YouTube somewhere of Glen and John Hartford doing “Great Balls of Fire,” bluegrass-style. Well, I was taping that and later the New Grass Revival learned that arrangement and that’s the one we performed. Courtney [Johnson, the banjo player in New Grass Revival] pretty much played the same chromatic run that he learned from John Hartford off of my tape of them doing it on TV.

I was really paying attention to him at that point and keeping up with him, buying his RCA records when I could find them down at Ernest Tubb. It got to where John was selling seats and doing good in larger places. John played at the basketball arena at Western Kentucky University where I grew up in Bowling Green. I think I was a senior in high school when John played there and all I know is that I couldn’t get there fast enough. But I had to march in the marching band at halftime for our football game at school. I wanted to get there so badly, I jumped in the car practically straight off the football field. It was really muddy and it started raining on us. I got there just when they were bringing the lights down for John Hartford and ran on in with my muddy band uniform.

That particular group that he had then was what he later told me he called the Iron Mountain Depot Band. Iron Mountain Depot was one of his last records, if not his last one, for RCA. The band was John, a keyboard player, bass, drums, and a twelve-string guitar. The next time he had a band style situation, it was what we call the Aereo-Plain Band with Tut Taylor, Norman Blake, and Vassar Clements. So that was a big change in direction for him.

What did you play in the marching band?

I played drums. Junior year, bass drum, and senior year I made it to snare. I guess I played “drum,” not “drums” plural. I played drum in the marching band and I played bass violin in the concert band. I got serious about bass and took lessons. I would take the bass fiddle home every night and practice and take it back the next day. All the kids would say, “Here he comes, carrying his bass.” I would later use the bass in professional applications here and there, as I did on this record.

Right, about that: I listened to the record before I read the liner notes —

I’m hoping that you liked it (laughs) you know what I mean? It’s supposed to sound good before people read the liner notes.

That’s the thing. I listened to it and I was trying to figure out who was playing, and then I read that it was you playing all of the instruments. I know that you play fiddle and mandolin, obviously, and I’ve seen you play lots of guitar, but I’ve never heard you play banjo or bass.

Yeah, nobody has. This totally blows my cover. But I picked up the five-string somewhere around 13 or 14 and started messing around with it. My parents had my granddad’s old Blue Comet five-string banjo. My mom played the guitar, and my dad played the fiddle. So, I got interested in banjo and I remember the first instruction book when I was a kid was the Pete Seeger book. After that, the next one I found was a Sonny Osborne book. That was really cool because I was a big fan of the Osborne Brothers.

And after that the Earl Scruggs book came out in the late ‘60s, and Alan Munde at this point was preaching Earl Scruggs to me. He’d say, “Fancy licks are fine, but they don’t mean anything if you can’t play like Earl.” I don’t think I took Earl for granted, but he was just one of those guys that I saw on TV my whole life. But when you start hauling down and trying to learn every note out of that book like Earl does it, it’s the great humbler. That’s when you find out the genius of Earl Scruggs. So, I’ve always played the banjo. Back when Courtney Johnson was in New Grass Revival, I’d get up generally every day and go to his camper. He made very strong coffee and we’d drink coffee and play guitar and banjo and we’d switch. Sometimes I’d play banjo and he played guitar, but usually more me on guitar, and we would learn things together. We learned John Hartford licks together and Alan Munde phrases and Bill Keith things that we could figure out together and go through the Scruggs book.

At that point I played a lot of banjo. When Béla Fleck and Pat Flynn joined New Grass Revival, the situation wasn’t the same. Sometimes Béla and I’d swap a little bit, but we didn’t have a dobro in the band anymore, so there wasn’t much reason for me to play guitar. I used to be a much better flat picker, but that’s the great thing about recording, I could just keep working on it until I got it. But just circling back to thinking about banjo picking, that’s one of the reasons I went ahead and played it myself, in that I watched and played with John a lot over a period of years, and I knew how he made the forward rolls and stuff. I am trying to play the banjo like John on the record. The other instruments sound more like myself but banjo and guitar, of course, I was trying to emulate certain things and phrases that John did.

I was impressed by how much it sounded like John Hartford-style banjo, especially on that instrumental, “Down.”

Well, thank you. Playing it all by yourself is fine, but it better sound good, because when you’re driving along in your car, if it’s not sounding good, it doesn’t matter who all played on it or what they went through. That’s the proof. Does it sound good to me? And these Hartford songs are kind of this way. When I have a reaction to music, it’s like, “Did I feel something as I listened to it?” These songs, they make me feel something.

And if anything, I’m hoping maybe through this record people can go back and dig through some of his early song work on RCA because probably a lot of people don’t know those records at all. As he aged, it was interesting to me that he got more traditional, got more old-time in his thinking, whereas when we met, we’d listen to Birds of Fire by the Mahavishnu Orchestra going down the road and try to figure out how to do some of those notes. There was just a heck of a lot of variety in his work. Later in life, he’s writing all these fiddle tunes, while early in his career, it was the songs.

This was a pre-pandemic project that is now being released post lockdown. Making a solo album where you play all of the instruments is the sort of thing that you would expect to have happened during that period of isolation.

We had it started down in Florida. [My wife] Lynn and I try to go down to Florida once a year if we can. Once the middle of November hits, there really isn’t much work, so I like to drive down to the beach, take a variety of instruments, and some kind of recording machine. Well, in typical fashion, I have this recording machine that I was not succeeding with. I was spending much more time messing with the stupid machine than I was getting to play my instruments.

I was jamming with our friend Donnie Sundal one night, and he asked, “What are you up to?” I said, “I’m trying to record some stuff by myself, but there’s a latency and I can’t seem to overdub in time. Something’s wrong.” And he said, “Oh, I bet I know what to do. I’ll stop by tomorrow.” So, Donnie stops by and his car is full of equipment. He brought a total ProTools rig, mics, preamps. He even brought another electric bass for me in case I didn’t have mine with me.

Once I started cutting these songs with Donnie digitally it was like, “Oh, now this is recording studio quality here.” I was originally only meaning to make tapes of these John Hartford songs to show the guys in the Sam Bush Band and then maybe we’d record them. I was not that far along in my thinking. I was really just at the beach so I could sit and make up tunes. But the joyful thing was to kind of sit and play John Hartford songs. As I started thinking about these tunes and everything, and when I started overdubbing them by myself digitally, I thought, “Well, maybe this could be a solo record.” And then, of course, we got shut down.

Rick Wheeler was the soundman and road manager for me and the band back then. Rick’s got an overdubbing room at his house. During the lockdown, we’d test and felt safe to be together and that’s when I got serious about working hard on the vocals and putting the banjo on. I tried putting some banjo down in Florida by myself, and I didn’t like any of it. A couple of the tunes I had to totally start over on.

Thanks to the generosity of Béla Fleck, I had some great-sounding low banjos to choose from. And the low one that I played the most was a Gold Tone. He had all wound strings on that banjo, which agreed with my lack of finesse with a right hand. He also loaned me one of John Hartford’s banjos, the one that he would tune to low D. But that one had thinner strings on it, and I didn’t feel I had the finesse to succeed on John’s banjo. It was set up in a lighter way whereas Béla’s was set up heavier for my claw to be able to get a better tone out of.

I started putting these tunes together, and I started thinking about that phrase “Radio John.” When New Grass Revival’s first album came out, there was a poem written about us, and it’s signed, “Radio John from Topanga Canyon.” Well, it was Hartford, but I think there was some kind of contractual thing where he could not use his name, John Hartford, on other albums or something. So, he just signed things as “Radio John,” which was his DJ name as a kid.

I started thinking about “Radio John” and wanted to write a song. I got together with John Pennell, Alison Krauss’s original bass player who wrote a lot of great songs that Alison recorded. We started writing this song over the phone during lockdown. We started making a list of all the things that we would try to mention in the song, and, man, we didn’t come close to being able to get all of the things that John was good at. I didn’t touch upon his beautiful calligraphy handwriting, and we couldn’t figure out a way to work 4×6 index cards into anything, but we just wanted to honor his many talents. Steamboat captain, singer, dancer, picker, writer.

I knew I wanted to involve the band and have Chris Brown on drums and it needed a better banjo picker than me. As it turned out, that was Wes Corbett’s first recording with our group. Once again, thanks to Béla’s generosity, Wes played John’s low-tuned banjo on “Radio John” and pulled beautiful tone out of it. I’m really happy with the way the song turned out and glad that the band could do it.

That’s such a great story and it’s such a beautiful project because of your personal connection to these songs.

Lynn phrased it the best when she said, “It’s your love letter to John Hartford’s music.” But making a record and playing everything yourself is not even close to being as much fun as playing with other people. I’m glad I did it once but the nostalgia for John is the joyful part of it, for sure. What’s funny is that after all these years, I made this record as a tribute to John and it’s probably my most acoustic record. Besides the electric bass. John’s old records had Norbert Putnam on electric bass, and then, of course, on Aereo-Plain, Randy Scruggs was playing electric bass. That sound kind of blended in with Hartford music for me.

Yeah, I can hear that. The tunes “Down” and “John McLaughlin,” definitely have an electric bass feel.

Yeah, oh, and speaking of “John McLaughlin,” there’s a certain way John played his banjo rolls there. Boy, when I’m listening back to the original version that I played on with John, I had forgotten that he had an octave low banjo that was tuned all the way down to A. God, that’s low.

That’s part of the fun with this record; getting to listen to your versions of these songs and then go back and listen to John’s versions. It’s interesting how much of the similarity you’ve captured while still making them unique.

That’s always the trick of trying to pay tribute to something while giving it another slant for people to hear. When I was recording, I was trying really hard to think of John’s phrasing and how he would sing it, and I did, for the most part, succeed. But now when I go back and listen to John’s version, I go, “Well, I don’t really sound like John but that’s good.”

That’s sort of like what I was saying earlier, about you and John as contemporaries while your music was also being influenced by him.

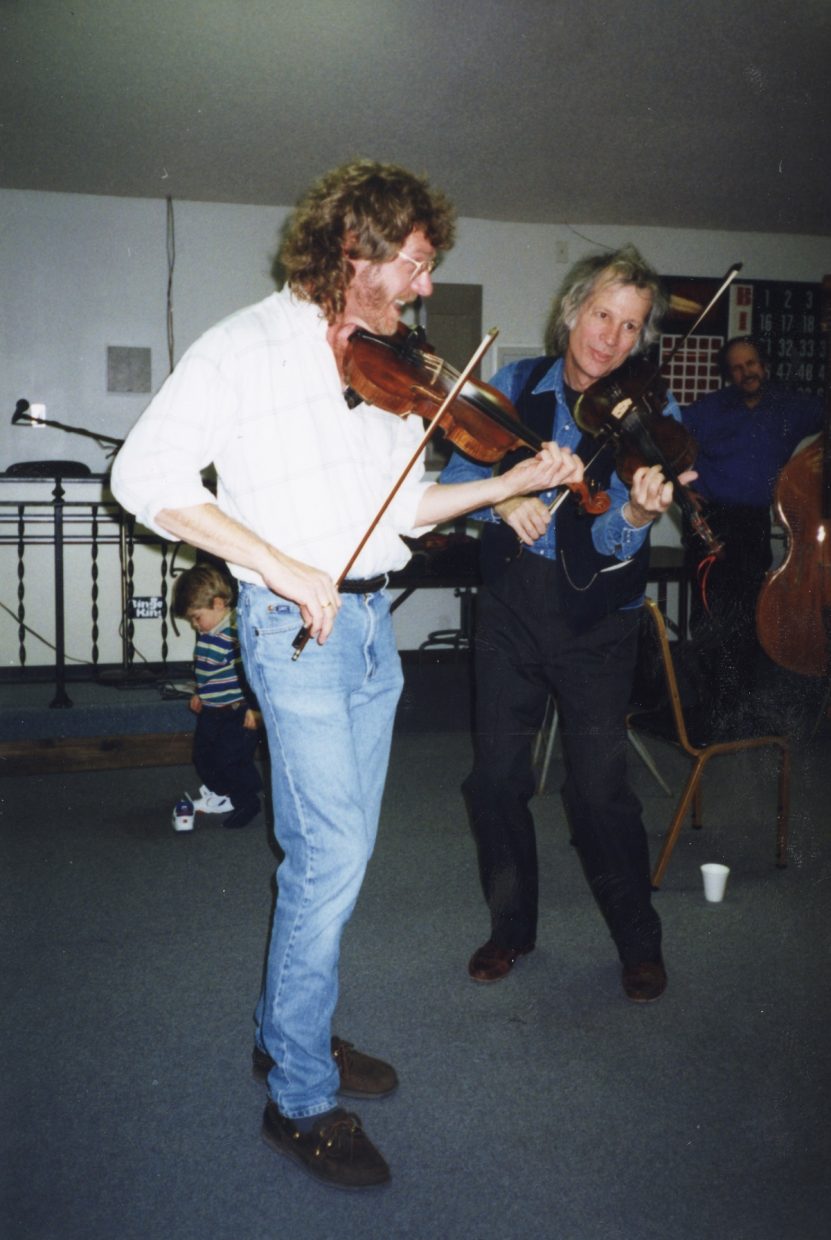

That’s the fortunate part of where I’ve been in that we became contemporaries. I was fortunate to get to know one of my heroes and play with him.

Photo Credit: Jeff Fasano