My fifth grade teacher, after announcing pop quizzes, would, without fail, remind my panicked classmates and I sitting at our desks to “Look down in desperation, look up for inspiration, but do not look side-to-side for information.” A memorable way to keep ten-year-olds from cheating on each other’s exams. There’s something about the adage that’s stuck with me twenty-five years on.

To this day, if I’m feeling desperate or helpless, my head droops down, oftentimes collapsing into the palms of my hands. I still also look up for answers to the unanswerable, the unknowable, or as Mrs. Schock put it, for “inspiration.” Sat at my desk once again, reading about last month’s flooding in Texas on this country’s 249th birthday, my head automatically fell into my hands and, just as quickly, my eyes lifted their gaze upwards. Above my computer, nestled in the Napa Valley Wooden Cassette Rack, something caught my eye, the audio cassette of One Fair Summer Evening by Nanci Griffith.

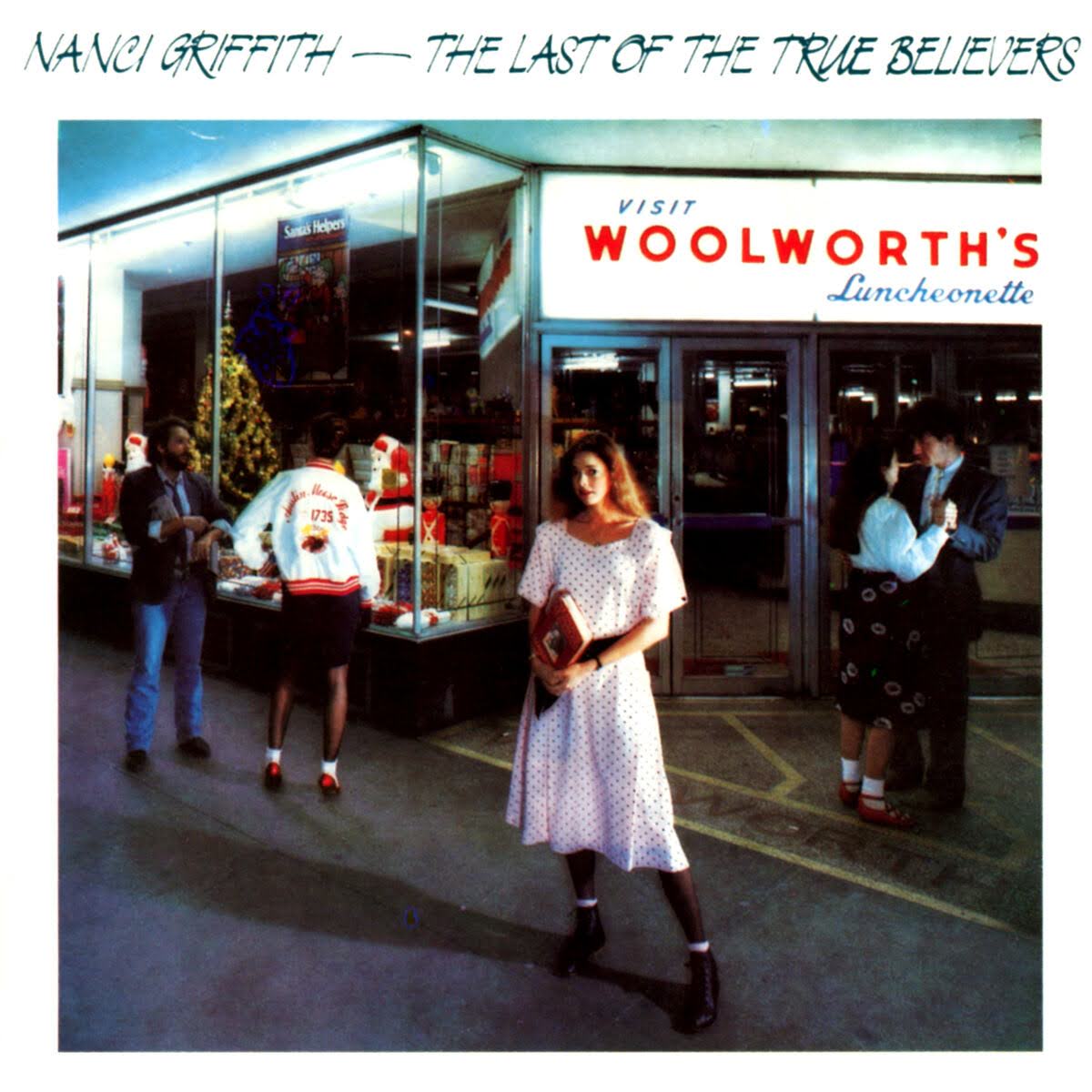

The GRAMMY-winning “Lone Star State of Mind” singer landed like a raindrop into this world on July 6, 1953, in Seguin, Texas, a small town in Guadalupe County in the watershed of the Guadalupe River. Raised in Austin, Griffith achieved international attention following the release of her breakthrough 1986 album, The Last of The True Believers, that showcased her impressive singing and songwriting, which she had honed in the decade prior alongside the likes of her Hill Country contemporaries Townes Van Zandt and Lyle Lovett.

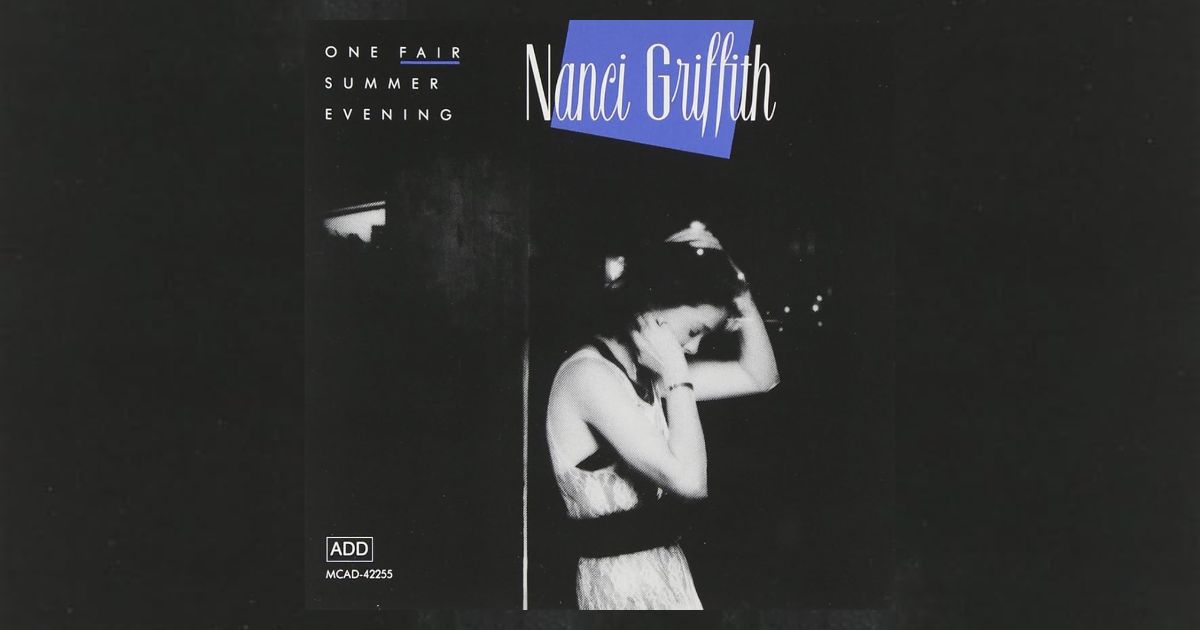

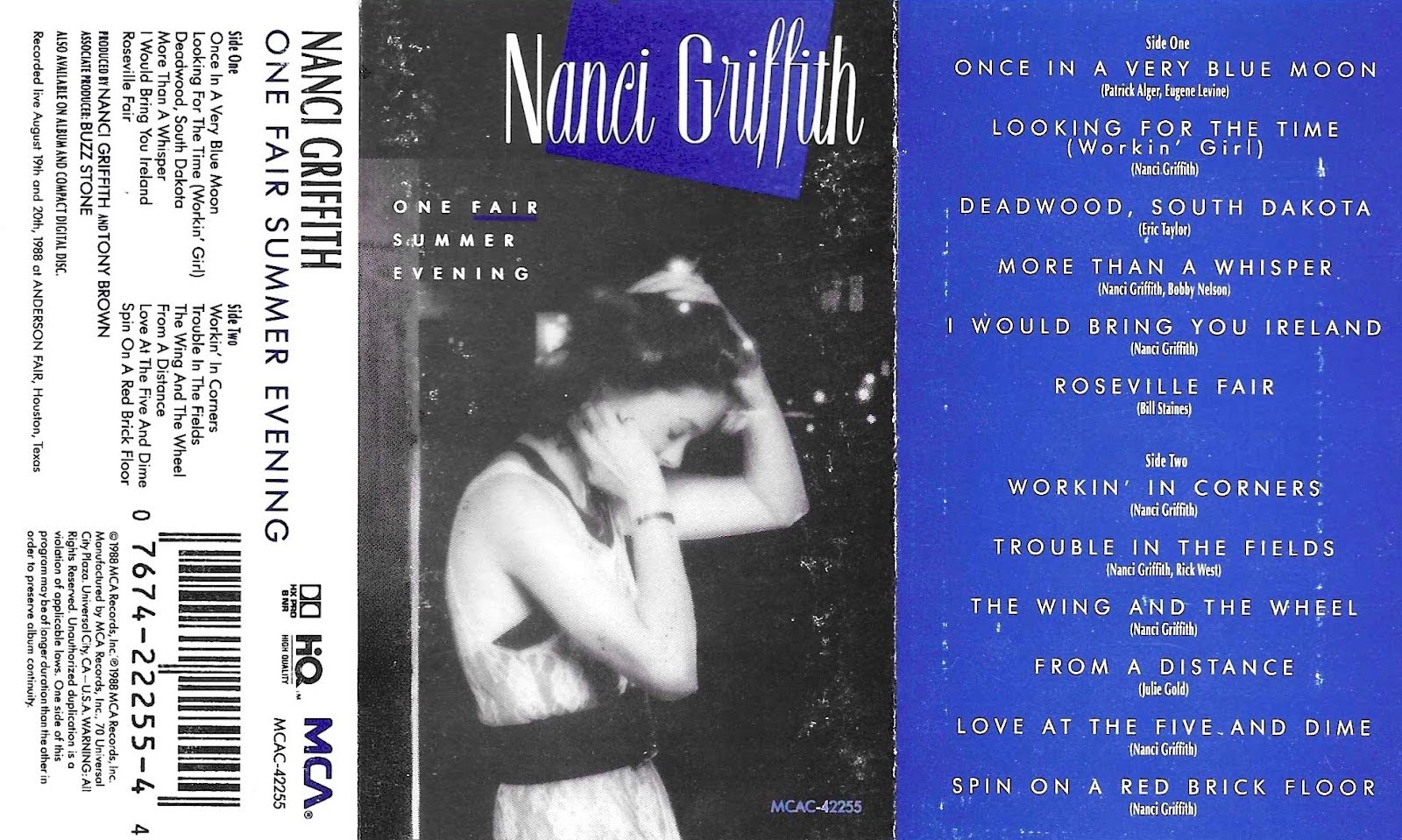

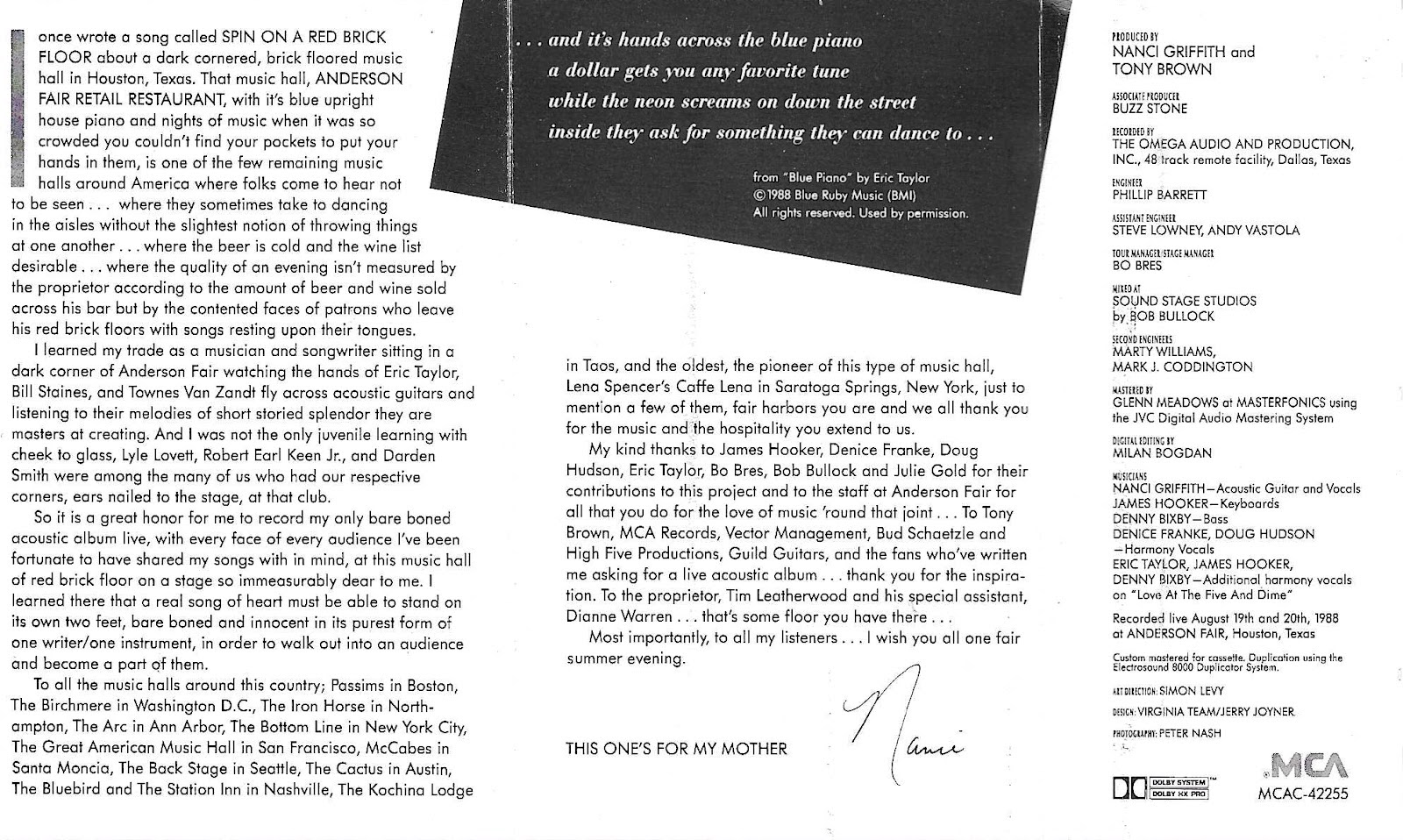

Griffith died on August 13, 2021, at the age of 68. Thirty-three years earlier, on August 19 and 20, 1988 – less than two months after that May’s blue moon – she recorded her sole live album, One Fair Summer Evening, at Anderson Fair, an intimate folk club in Houston. It’s a remarkable recording, not just for how good Griffith’s songs sound stripped of the instrumental flourishes that colored her studio albums up to that point, but the Texas charm she provides in the banter between songs.

While introducing “Trouble in The Fields,” she jokes self-deprecatingly, “Most of my mother’s family came from way out in West Texas in a little town called Lockney, which is somewhere close to Lubbock, but not too close to Lubbock. Nobody likes to be too close to Lubbock.”

The crowd laughs, hysterically.

She continues with her squeaky soliloquy, one long run-on sentence without much pause for breath, “My great aunt Nettie Mae said that surviving the Great Depression on a farm was not easy and she understands why the young farmers nowadays are having such a hard time, because she went through it herself and the dust blew so hard during the Great Depression on her farm that she said she was afraid to go to sleep at night, because she was afraid the dust would blow so hard one night that she’d wake up the next morning and find herself living in Oklahoma and she by God didn’t want to live in Oklahoma.”

The audience, cackling louder now and showering Griffith’s gift of gab with rounds of applause, quickly quiets themselves as Griffith shifts her tone and launches into the song about her family’s trials and tribulations being farmers in Texas during the Dust Bowl, singing the words: “And all this trouble in our fields/ If this rain can fall, these wounds can heal.”

Sometimes, we look up in desperation as well, for any precipitation the sky can offer us.

In the introduction to the next song, “The Wing and The Wheel,” Griffith tells her captive crowd, “There’s no need for any human being to ever be complacent.” The emotional whiplash might be too much to take, stark laughter swiftly shifting gears to deadpan seriousness, if the sincerity in the songs didn’t shine through with each passing line: “The wing and the wheel, they carry things away/ Whether it’s me that does the leavin’ or the love that flies away/ The moon outside my window looks so lonely tonight/ Oh, there’s a chunk out of its middle, big enough for an old fool to hide.”

Ten years later, in August 1998, Griffith’s relationship with her home state had become fraught. She wrote and sent letters to every major newspaper in Texas – the Dallas Morning News, the Houston and Austin Chronicles, the Austin-American Statesman, Texas Monthly – after a poor critical reception to her album Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back to Bountiful), released the month prior. In her letter, she defiantly rails, “There has always been a certain amount of pathos within artists who leave their sacred bountiful homes of birth for the benefit of preserving their own belief in their art—especially in cases such as my own where my native soil that I have so championed around this globe has done its best to choke whatever dignity I carried within me.” In the probing missive, she references Thomas Wolfe, whose own novels so severely damaged his reputation in his hometown of Asheville, North Carolina – which last year was decimated by the historic flooding of Hurricane Helene – he never returned.

The full moon in July is otherwise called a “Buck Moon,” named for the time of year the male deer’s antlers grow anew and hunters can track them more easily midday. This year, the Buck Moon swung across a fair, summer evening sky over Texas on July 12th, barely a week after the floods. That night Luke Borchelt, a country musician and singer-songwriter from Maryland, was seated at a bar in Austin. The night prior, he had performed at Parish, a club in the heart of the state’s capitol, right near where a Woolworth’s once stood at Sixth Street and Congress Ave. The very same shop Griffith sang about in her “Love at The Five and Dime” – and is pictured in front of on the album cover for The Last of The True Believers.

After striking up a conversation with a local patron at the bar, Borchelt was asked, “You’re a country singer? Could we do a concert tomorrow to raise money?” Borchelt agreed. So it often goes with Texans: forward, empathetic and community-oriented. Prior to becoming a full-time musician, Borchelt worked for Mercy Chefs, the Virginia-based, disaster relief non-profit.

“I managed logistics and the distribution of meals in disaster areas. That was my passion. It’s also where I got my musical start. After hours, I would play for the chefs. Disaster is a part of my story.”

As Borchelt recounts his journey, it sounds like a country song. There’s a rhythm to his speech that’s musical. He tells me “…there’s a stereotype of ‘badass’ Texans,” but in the wake of the floods, the “Every Rain” singer says, “I can’t say enough about the amount of people that showed up. We asked them ‘What brought you here?,’ and they would say, ‘I’m a Texan. We just show up.’”

After his performance in Austin, Borchelt headed to volunteer with Mercy Chefs, who had stationed themselves at a church in Kerrville to prepare and serve meals to evacuees, first responders, and search and rescue teams. Since the intense rains fell on July 4 in the central part of the state, 136 people lost their lives – 116 of which were lost in Kerr County.

In the flash flood’s waters, which crested at 30 feet, lay Camp Mystic – a girls’ summer camp situated alongside the banks of the Guadalupe River, northwest of Seguin. It was there that 27 people, counselors and campers, mostly children, died during one of the most tragic natural disasters in recent memory.

The six different flags that have waved over Texas throughout its history – some more star-spangled than others – have always flown over a proud people. When I speak to Mercy Chefs’ Ashbi Wilson, the managing chef on the deployment teams in Kerrville and Ingram, it’s no surprise she’s proud of her Texas roots. She lived in Kerrville for eight years before relocating southeast to her current home in Wimberley. At 21 years-old, before she became a chef, she spent a summer as a counselor at Camp Mystic, based on the recommendation of a professor at the local college, Schreiner University.

Regarding Camp Mystic she recalls, “Mystic is a really special place. Everybody was so warm and welcoming. Everybody was really just there to be encouraging and to have fun, and to help these girls, growing up to be young women.”

Hours before she got the call to deploy to Kerr County in early July, her bags were already packed. “It was a lot more personal this time, so I was ready to go,” she tells me. “Disasters are always both devastating and inspiring at the same time. So, even though there’s been so much heaviness and devastation around the lives and the places lost, it’s still really rewarding and inspiring to watch the community, and people from all over the state, and the first responders from all over the country and all over the world come in and do the work that’s needed.”

If these rains can fall, these wounds can heal.

Thousands of Texans called FEMA for assistance, and in the days following the torrential downpours, those calls were left unanswered, leaving recovery efforts largely in the hands of local authorities and volunteers. Firefighters from Mexico, a nation whose flag once flew over Texas, travelled north to Kerrville, and served a critical role in search and rescue operations. Earlier this month, after several Texas lawmakers fled the state in protest of a vote in the State Senate to gerrymander congressional districts along racial lines, one of their peers called upon a different federal agency, the FBI, to bring them back home. Is it any wonder why someone with such deep Texas roots as Nanci Griffith would disavow her home state?

Simultaneously, from where I write in Southern California, taqueros in East Los Angeles, farm workers in Camarillo, and day-laborers in the parking lots of Home Depots strewn across the city are being hunted like bucks at midday by armed and masked agents of the state, taken into federal custody to be deported to Tijuana, where there are now makeshift slums filled with deportees. In January, Mexican firefighters again headed north to volunteer to battle the blazes that burned across various pockets of the sprawling metropolis. Fire and I.C.E.

The desperation and helplessness one is inclined to feel while watching disasters both natural and unnatural unfold can be crippling. You don’t know how to do anything but languish in hopelessness and hang your head in shame, but as Wilson says, disasters can be both devastating and inspiring, no matter which way you look. Oftentimes, we turn to music to guide us through the dark and remove us from our solitude.

A live record gives its listener a glimpse into a communal space from afar, a moment captured crystalline and pure. Griffith’s One Fair Summer Evening served as my reminder that, not only in Texas, but everywhere a human draws breath, that “there’s no need for any human being to ever be complacent…” After all, “if these rains can fall, these wounds can heal.”

Donate to support flood relief in Texas by giving to the Community Foundation of the Texas Hill Country here. Learn more and support Mercy Chefs here.

Scans by Shane Greenberg, That Scans.