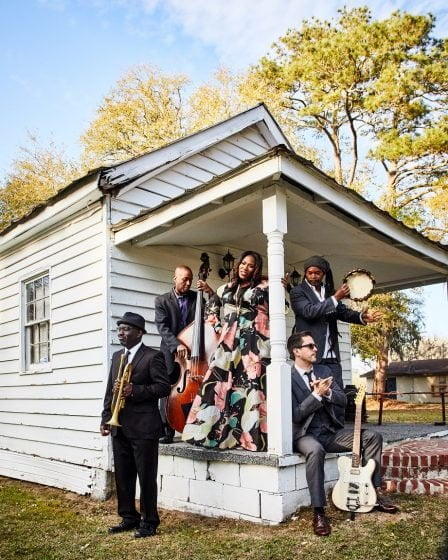

You don’t need to know the first thing about Gullah culture to appreciate Good Time, the second album by the South Carolina quintet Ranky Tanky. But each song provides a short lesson on this little-known corner of American music.

Take “Sometime,” an absolute jam that’s so fast, so breakneck that you have to wonder how the musicians can keep up with it. The rhythm section sets the white-knuckle pace, with drummer Quentin Baxter playing his snare like he’s an entire fife-and-drum band and Kevin Hamilton’s nimble bass adding a percolating low end. Vocalist Quiana Parler instigates a boisterous call and response with her bandmates, hitting high notes like she’s in church. Charlton Singleton’s trumpet snakes fluidly around the other instruments, while Clay Ross interjects a quick guitar solo that sound like New Orleans by way of Mali.

Delirious and joyous, “Sometime” presents all the individual elements of Gullah music, tracing a lineage through the U.S. and back to Africa. Never as popular as zydeco in Louisiana or rural blues in the Delta, it nevertheless has a unique sound, at once fresh and familiar as the instruments interact energetically with each other. Gullah culture developed along the South Carolina coast and on the Sea Islands, extending down into Georgia where it became known as Geechee culture.

It is a culture weighted with history, but perhaps the most remarkable thing about Ranky Tanky is how they work around that history, taking it into account but never letting their music settle into a revivalist vein. Good Time lives up to its title by sounding perfectly present tense. “We have a good time, as a band,” says Quiana Parler. “When I deliver these songs, I’m having so much fun onstage.”

They have taken that joy around the world, too. When they spoke to the Bluegrass Situation, the band was sitting in a hotel lobby in Madrid, where they were enjoying a day off from touring and getting ready to take in the sites of Spain.

BGS: Do audiences respond differently to your music in Europe than they do in America?

Clay Ross: Our experiences at festivals in Europe have probably been among our best gigs ever. The audiences are engaged on a different level. They’re really invested. We’re a band that maybe they’ve never heard of or seen, because in a lot of cases it’s the first time we’re playing that city. But when we do a crowd participation thing in our show, you can see every person engaging with the music, from the front of the stage all the way to the back of the room. It might be 5,000 people, but they’re all right there with you. It’s been a pretty powerful thing. I don’t know if there’s a greater cultural appreciation for music here or perhaps we’re more novel here than we are in our own country.

Quiana Parler: The support at home has been unbelievable, but overseas it’s completely different. They appreciate you differently. We don’t take any of it for granted, though. We’ve played only five or six times at home in the past five or six years because we’ve been so busy. What a blessing.

CR: By far the vast majority of our performances have been in the U.S., so we don’t have as much to compare it to. But the two dozen concerts that we have done over here, every single one of them has been sold out. And every single one of them has been met with an overwhelming response. We try to make our live shows exciting. We’re a touring band, after all. We’re live performers and improvisers, so every concert is a different event.

That seems to make the music very urgent and immediate. The new album doesn’t sound like a revivalist project.

QP: That’s our duty, I like to say. It’s a way of life for us. We went into this with good intentions — to get the message of the Gullah people out there internationally — and I think when you go into a project like this with something positive, you really get what you put into it. When Clay brought the idea for this band to us, we decided that we had to figure out a way to get the message across and have it be relatable. It couldn’t get lost in translation. So we had to remain true to the Gullah culture. We couldn’t sugarcoat anything. We had to make it very authentic.

CR: One thing I think is very special about this band is that we have different perspectives on that culture. Four of the group members are descendants of the culture and have their own unique cultural experiences growing up. I myself grew up around it and consider myself a disciple of the music, but I’m not a Gullah descendant and I’m not integrated into it the same way. I think that process has been special for us, because it allows us to see things in fresh ways and to qualify those ideas against actual experiences. But most of all we just want to make sure we honor and respect the Gullah culture.

Do you find that people are familiar with Gullah culture? Do they know where you’re coming from?

QP: Not really. People know about zydeco and other cultures, but we’ve never had much focus on the Gullah community, which is the root. But people are very open to it and very intrigued by it. They want to know more, which is a good thing. It’s been received very well, thank you Jesus.

Why do you think Gullah culture has been ignored?

QP: I have no idea. I don’t know. It’s not in history books either. I didn’t learn about this in school. Somehow it got put away. It’s sad.

On both of your albums, you’re going back and finding older songs to add to your repertoire. What is that process like?

CR: I brought a lot of that repertoire to the group for their consideration. I’ll bring in a field recording or some ideas based on research that I’ve done. We’ve studied the music of Bessie Jones, the field recordings of people like Alan Lomax. He and other folklorists visited the Sea Islands in Georgia and South Carolina and created books and recordings of that material.

Those places were so remote, so geographically isolated, so those songs and traditions would have been passed down through a hundred years or more of oral tradition. Now things are changing with technology and those places aren’t so isolated. It’s become a little more difficult to preserve those traditions, so we want to honor the people who passed this music down through so many generations while adding our own voices.

What is your background with Gullah music?

QP: It’s the church! It’s all embedded in the church. Most of us grew up in church and that’s where we learned a lot of these songs. There might be a few differences in the words or the rhythms of a song from one church to another, but it’s still the same. That’s how it’s been for generations and generations, and I’m still passing it down to my children. My son is 11 years old and playing drums in church. They’re playing the same songs that we grew up singing. It’s a little different with the millennials, but it’s the same thing. It’s in their DNA. My son was born into Gullah culture on his dad’s side, so it’s in his blood.

CR: When I came to the band members three or four years ago, it was maybe more of an academic idea: Let’s do these specific public domain songs with these unique arrangements and put our own spin on them. It was very specific material. What I think has been the most special thing about evolution is that with this new album, we’re writing our own songs inspired by just spending time together and playing concerts together. Our goal in the writing process is to create a seamless bridge between the traditional material and our original material. If you hear it and you think something doesn’t fit, that would represent a failure on our part artistically. We’re very conscious of that during the writing process.

What is that process like? Is it something where one of you brings ideas to the band, or are you working these out together?

CR: A lot of the material — I would say the frame of the house — might start with Quiana in soundcheck. Maybe Kevin [Hamilton] starts a riff on his bass and Quiana sings a line, then from that point something that just feels good can be the flame that starts a fire. We start to shape it, and everybody contributes. Everybody designs their own parts and everyone contributes to the shape of the songs. I end up writing a lot of the words, but that’s just something I’ve always liked to do. It’s a way I can contribute.

What can you tell me about the song “Freedom”?

QP: The idea for “Freedom” is something I came up with because of something I was going through personally. And it just so happened to coincide with adversity that other people have had to deal with. African people have always dealt with adversity. We all want the same thing at the end of the day. We all want freedom. That’s something Clay emphasizes in the lyrics—that struggle for freedom.

CR: When Quiana came up with that idea for “Freedom,” I went home and wrote ten verses about that idea. Then we ended up picking up three or four that worked the best. It’s a bit like that. But everybody contributed, and that’s something I’m grateful for. We’ve had this amazing opportunity to align our powers.

Dealing with adversity and struggle seems to be a theme on the album. “Beat ‘Em Down” is a good example. It sounds like a violent phrase, but the song clarifies: “Beat ‘em down with love.”

QP: Kill ‘em with kindness. Hate is such a strong word, and I’ve always [believed] that you love someone instead of hating them. You love the hell out of them! You don’t fight fire with fire. You reciprocate with love and compassion. That’s the only thing you can do.

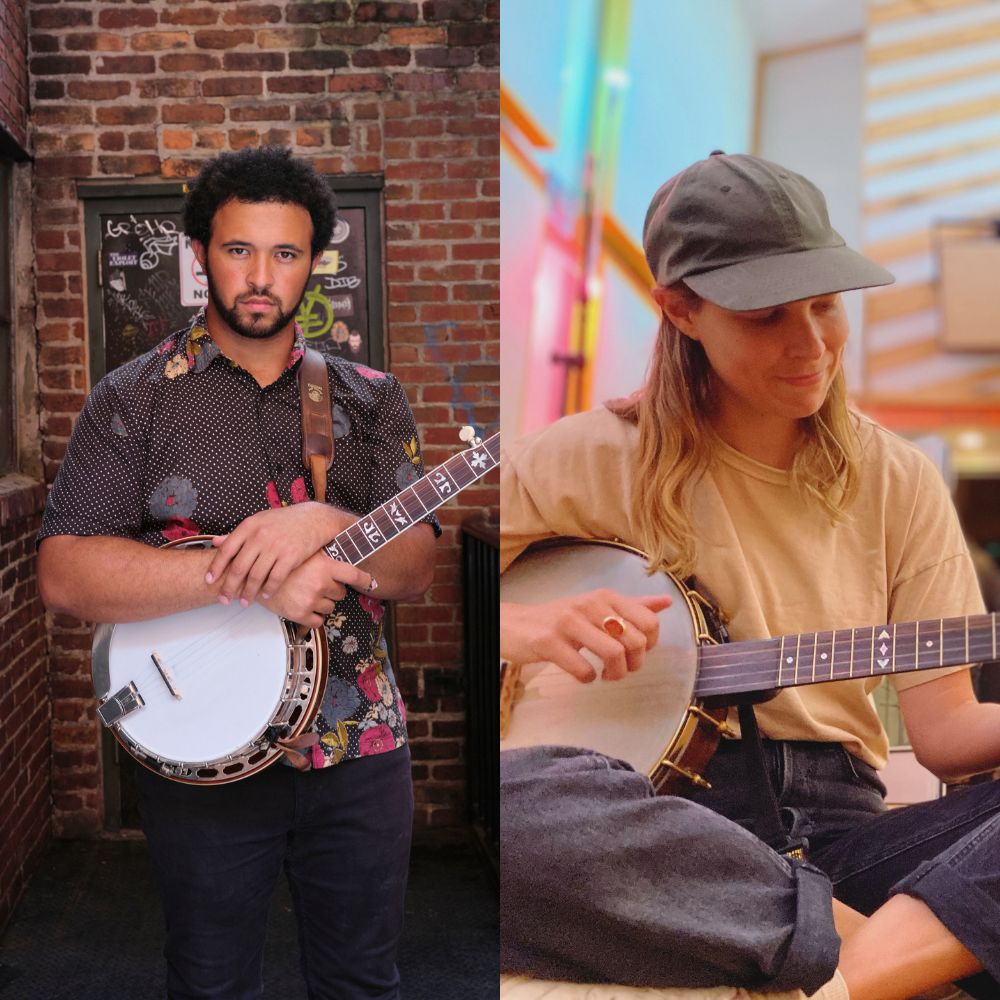

Lede photo credit: Sully Sullivan for Garden & Gun Magazine

Church photo credit: Peter Frank Edwards