(Editor’s Note: Sign up here to receive Good Country issues when they launch, direct to your email inbox via Substack.)

Few words stir up conflict in country music circles the way “authenticity” does. While debates over authenticity rage within every corner of the arts, the tension is especially potent in country, whose unofficial tagline is, after all, a commitment to honest simplicity: “Three chords and the truth.” While “truth” can be a broad umbrella to work under, within country music it tends to encompass a longstanding commitment to sharing the stories and experiences of everyday people, in particular those of the rural working class.

Accordingly, an adherence to and celebration of the very concept of authenticity – nebulous as it may be – is as baked into country music culture as an anti-establishment sentiment is inherent to punk music. Listen to country radio, though, and you might have a hard time finding it, particularly as the bro country of the mid-teens, though finally waning in popularity, still dominates the majority of terrestrial country airwaves.

Rather, at the time of this writing the number one country song in America is “I Remember Everything,” a duet between the relatively new artist Zach Bryan and one of the genre’s more adventurous stars, Kacey Musgraves. As a song, “I Remember Everything” isn’t necessarily groundbreaking. Bryan’s and Musgraves’ voices play nicely off one another, with his achy grit contrasting sweetly with her smooth twang. The production is simple, underdone even, and lyrically the track travels well-trod territory: romantic heartbreak.

So, what, then, has kept “I Remember Everything” firmly situated in that top spot for 14 straight weeks (and counting)?

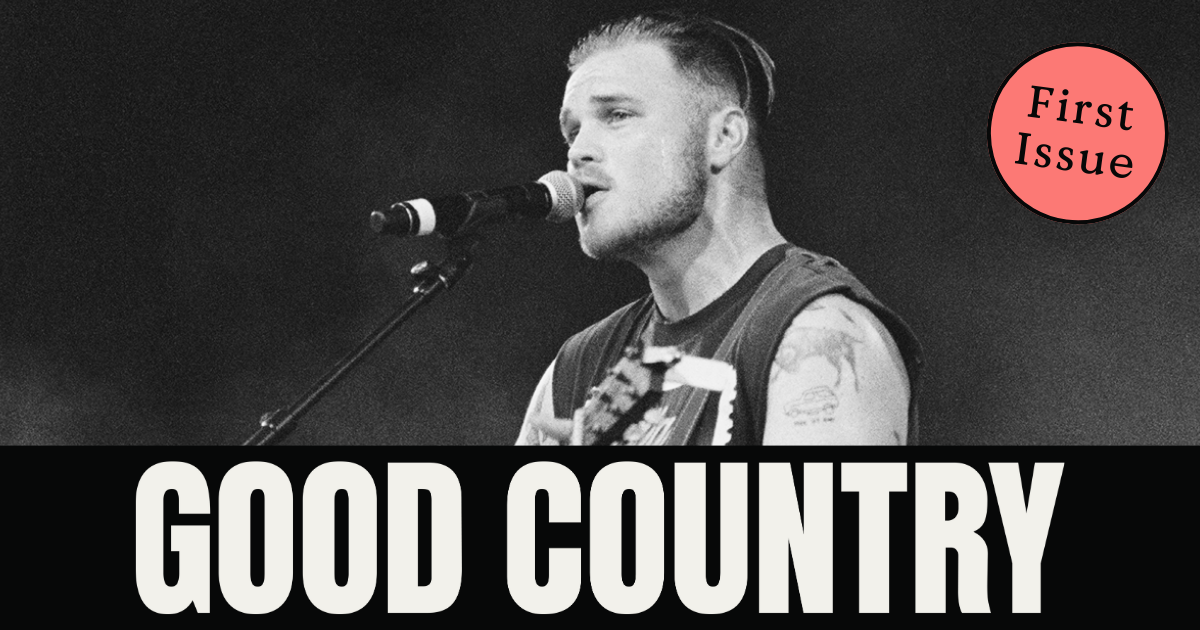

If you’ve paid even the least bit of attention to country music in the last couple of years, you’ve no doubt encountered Zach Bryan and his genuinely singular approach to the genre. With his raw sound, confessional lyrics, and decidedly DIY approach to business, Bryan radiates the kind of authenticity that fans crave. He joins a host of other recently established and emerging artists – including but not limited to Tyler Childers, Lainey Wilson, Colter Wall, and Billy Strings – who found success by foregoing the traditional route to country stardom, one that typically involves following an out-of-date formula honed over time by profit-driven record labels.

Zach Bryan debuted with DeAnn in 2019, finding an audience online thanks to the viral success of “Heading South” on DeAnn’s follow-up Elisabeth. He quickly built a fanbase on TikTok and YouTube before releasing his 2022 breakout LP, American Heartbreak, which had more opening week streams than any other country album that year. In the lead-up to American Heartbreak, Bryan, who served as an active-duty member of the U.S. Navy for eight years, was honorably discharged in 2021 so he could pursue music in earnest.

In addition to topping charts, American Heartbreak set itself apart from the rest of the year’s crop with its unadorned production, heavily narrative songwriting, and sheer ambition – the record clocks in at a lofty 34 tracks, with less filler than one would anticipate. The album’s biggest single, “Something in the Orange,” earned Bryan a Grammy nomination for Best Country Solo Performance and, for a time, landed him atop Billboard’s Top Songwriters chart.

That record, along with a handful of EPs and loosies released in between, teed Bryan up for his 2023 self-titled LP, a much more focused effort (a mere 16 tracks!) that found Bryan firmly situated as a real-deal country star, one who can tap the likes of Musgraves, the War and Treaty, Sierra Ferrell, and the Lumineers to come join the proceedings. While it no doubt shows the depth of his rolodex, that guest roster also points at the breadth of Bryan’s influence, as each artist comes from a different part of the broader country/Americana ecosystem.

‘First ever’ is fuckn insane, one of the best songwriters to ever do it https://t.co/GdkuWiWDvq

— Zach Bryan (@zachlanebryan) January 9, 2024

And while he considers himself a country artist, Bryan’s roots are more indebted to the folk-rock revival of the late-aughts and early teens, when acoustic acts like Mumford & Sons and the Lumineers grew so big as to cross over into Top 40, eventually helping spur an explosion in popularity for Americana and roots-adjacent music. It’s fitting, then, that the Lumineers feature on Zach Bryan, joining on the track “Spotless” so seamlessly it isn’t always easy to tell who is singing: Bryan or Lumineers frontman Jeremiah Fraites.

It’s on these collaborations, in particular, that you can hear Bryan’s joy at being able to do what he loves. His vocals are raw, but never phoned in; in fact, sometimes he seems to be straining so hard to communicate a particular emotion that you worry his voice will give out. It never does.

In other words, Bryan is a fan’s musician, one who geeks out about his favorite artists the way his own fans do about him. In a post about the duo the War and Treaty, who joined Bryan on the standout Zach Bryan cut “Hey Driver,” he writes, “I can tell you the first time I heard War and Treaty live and I looked to the person next to me and said, ‘Are you hearing this?’ I talked to them later that night and they were the kindest couple I’d ever met.” In the same post, he says of the Lumineers, “I can tell you about how when my Mom went on home I got the Lumineers tattoo on my tricep after hearing ‘Long Way From Home’ for the first time and how Wes [Schultz] and Jeremiah are some of the most welcoming humans I’ve ever met.”

This post points to a major piece of both Bryan’s appeal and the air of authenticity that surrounds him: His direct line of communication with his fans. He manages his social media accounts himself and is no stranger to getting vulnerable in his messaging, often posting progress updates on new songs he’s working on or taking a moment to express gratitude for his success. For fans, it’s almost like there are no barriers between them and Bryan, which reinforces the relatability at the core of his music.

The beating heart of Zach Bryan, for me, is “East Side of Sorrow,” a song that grapples with hope and religious faith by connecting the grief Bryan felt after losing his mother to his time being shipped overseas while serving in the Navy. Despite – or perhaps because of – these vivid references to specific experiences, like being “shipped… off in a motorcade” and losing his mother “in a waiting room after sleeping there for a week or two,” the song is deeply emotional and relatable, a wrenching but empowering anthem encouraging the hopeless to try to keep it moving. These days, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone who couldn’t use such a message, this writer included – Apple Music tells me it was my most-played song of 2023.

It would be – and for a lot of folks, already is – easy to accept Bryan’s every word, to believe that his hardscrabble songs about “rot-gut whiskey” and manual labor are honest reflections of the life he’s lived and the person he is. Then there’s the cynical interpretation, that Bryan’s anti-marketing is, actually, still marketing, that a young musician could only know so much of the realities of the struggle of the working class, that it’s the same twang to a different tune. Bryan has, after all, had a few bumps along his road to fame, including some less than flattering encounters with police that negate his humble personal.

But the truth, as it so often is, is likely somewhere in the middle. With such personal material, it’s easy to trace one of Bryan’s songs to its point of inspiration – “East Side of Sorrow,” for example, is undoubtedly ripped right out of his lived experience. And Bryan isn’t afraid to admit the gaps in his experience, like when on “Tradesman” he sings, “The only callous I’ve grown is in my mind.” Compare that to, say, the sheer tone deafness of a song like Blake Shelton’s “Minimum Wage” and Bryan’s instances of stretching the truth feel trivial.

Bryan is only the latest in a long line of country artists for whom authenticity is both a blessing and a curse. Genre giants like Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings are often held up as unimpeachably authentic pillars of the genre, despite weathering their own brushes with the authenticity police earlier in their careers. And these debates, which tend to center white, straight, cisgender men, aren’t nearly as hostile in their scrutiny as they are for marginalized artists, against whom the idea of authenticity is typically wielded as a gatekeeping weapon.

Wherever you fall on Zach Bryan, it’s hard to deny that the gravel-voiced, baby-faced boy from Oklahoma has changed the very fabric of contemporary country music. What he does with that power moving forward could break the genre open for good, making space for artists with unusual paths, atypical backgrounds and a disregard for the flavor of the week. If Zach Bryan is who he says he is, he may very well do it.

Photo Credit: Louis Nice