In June 2017, F.J. McMahon played his first show in a lifetime. He took the stage with the Boston psych-folk group Quilt as his backing band and ran through the nine songs on his lone album, 1969’s Spirit of the Golden Juice. Those songs had been collecting dust for nearly 50 years. “I had to go through the entire thing and re-learn everything — every chord, every lyric,” he says. To his surprise, and perhaps no one else’s, the songs sounded sturdy and strong, speaking as loudly in the 2010s as they did in the 1960s.

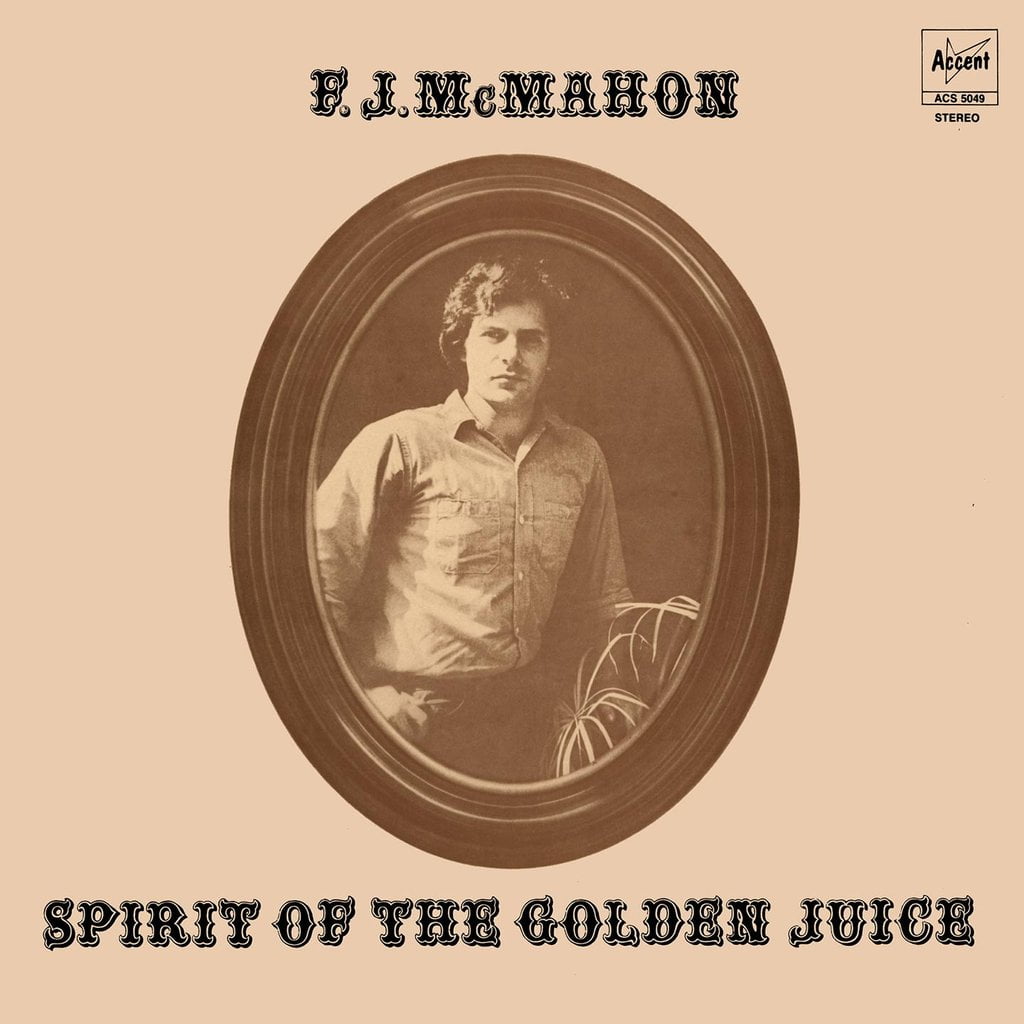

Fresh out of the Air Force, McMahon recorded Spirit of the Golden Juice in 1969 for Accent Records, a small L.A. label that had few ideas how to market a folk-rock singer/songwriter. No one heard it. No one cared. (The title, it should be noted, refers to whiskey, McMahon’s favored intoxicant at the time.) Decades later, it became a crate-digger’s treasure: one of those small-press releases that never finds an audience on its initial release and ends up at estate sales and dollar bins. Passed around from one vinyl collector to another, Spirit inspired an obsessiveness among fans who had no idea who F.J. McMahon was.

The renewed interest led to small reissues, but those pressings have become almost as rare as the original. That makes the new version by Anthology Recordings such a godsend to fans, new and old. “It’s very bizarre,” he says of his revived career. “The number of people I’ve run into, musicians and people in the music industry, they just look at me wide-eyed, shake their heads, and say this never happens. I don’t know what to make of it. It’s incredible.”

When did you realize there was a cult built up around this album?

I didn’t realize that until I started reading a little thing here and a little thing there. I’m going, “Really? For real?” I knew something was going on around 2002, when a label called Wild Places issued a bootleg, and the guy who was running it told me a bunch of friends from around the world liked it. I had no idea. I stopped playing right around the end of 1974 although, in the ‘80s, there were a couple jam bands and rockabilly psychedelic bands that we got together for fun. We’d do open mic nights, stuff like that, but nothing serious.

When music didn’t work out as a career, what did you do instead?

I needed a job. Because I was a former hippie guitar player, I didn’t really have a trade. This was the mid ‘70s, and the hot thing was electronics and computers. That was what was making the world go round. Going to school would have been fine, but I knew it would take a long time. If you wanted to get the best education and do it quickly, you go to the Navy. You go to their schools and you work on their airplanes. It worked like a charm. I had a career for about 26 or 27 years as a field computer engineer.

What does that job entail?

We’re talking about computers in the ‘70s and ‘80s. It took an army of technicians to keep them going. We had to trouble-shoot and repair and replace parts constantly. It isn’t like now, where one breaks and you just throw it away and buy a new computer. You had to know all your software and languages and stuff like that. I was on the road all the time, going from customer to customer, repairing computers for everybody from Air Force bases to show business to lawyers to whoever.

That sounds like a lot like touring.

I would do anywhere from 400 to 500 miles a week.

Backing up a bit, how did you get into music in the first place?

I started off in surf bands in high school. That was right around the time the folk boom was happening, and I started picking up on that. I liked it because there’s a lot more depth and storytelling to it. Between 1964 and 1966, music just went through this huge revolution. That was the most wonderful thing. I had forgotten all about it until a few years ago, when some guy gave me a CD he had taped decades ago off a local AM radio station. It’s an hour program, and it was so cool because you get to hear the Byrds and Judy Collins and then you’d hear “Tequila” and something else. All this incredible music was being played on the same stations. That’s the way it used to be. You could hear all this different stuff.

From 1968 to 1970, there were so many amazing bands coming out, and the music was just staggering. There’s been nothing like it since. You didn’t have computers, so you actually had to play it and record it. If you wanted to cut and paste, you had to get the scissors and tape. Bands really had to get their chops up. And then you’ve got George Martin with a four-track doing these incredible things. He made Sgt. Pepper on a four-track. Just think about that for a minute. And the influx of folk music, especially Bob Dylan for lyrics and ideas, just changed everything.

Your album falls between those two poles. It’s obviously influenced by folk-rock, but the production is very innovative. I feel like I can tell the shape of the room when I’m listening to these songs.

I love that. The production of it was very bare bones. When we did the bass, drums, and rhythm guitar, we were in a fairly good-size room at this place called PD Sound Studios in the San Fernando Valley. Then we went back to Scott Seely’s studio at Accent Records, which had a little four-track machine. I did the vocals and lead guitar there. I can’t remember the name of the mastering studio, but I remember the Beach Boys had just left and in comes me with my little folk record. I was intimidated, to say the least.

Being out there in California, did you feel like part of a larger scene? Did you feel like you were involved in that revolution?

Absolutely. I started playing a few old clubs and getting with some old friends to play bar-band gigs for weekend money. But I was also heavily involved in the anti-war thing, so I was trying to get my buddies who hadn’t gone yet not to go in the military. I didn’t want them going over there, so I was involved. Music was a big part of that movement. Everything was music at the time. There was a feeling in the ’60s that, if you saw somebody else with long hair, you knew they felt more or less like you did. There was a feeling guaranteed between the two of you that music could change the world. That may be naïve, but it was an honest-to-God feeling we had.

Is that a belief you still hold?

Well, you don’t always see things right away. It’s not like painting a barn white. Okay, it’s a white barn. You can see it clearly. But somebody may hear a song and it might spark an idea. It might change what they’re doing or how they’re thinking. That certainly happened to me.

One of my music heroes is Hoyt Axton. He’s best known as an actor, and you can see him in Gremlins and some other movies. But he was a folk singer in the ’60s, and I used to go down and see him at this place called the Troubadour, where pretty much everybody used to play. His sense of humor, his intelligence, and his insight were remarkable. He would put a political statement into his songs, but it would be a funny thing, a joke or something that wouldn’t ring true to you until after you’d left the concert and gone home. Then you’d think, “Yeah, he was right!”

Your album has worked in a similar way. It took 50 years to sink in, but it’s clear a new generation of listeners feel you have something to say.

I’ve been told that. I’ve been told that by people who weren’t even alive when it was recorded. I think it’s beautiful that music from a different time can still have an impact on people so many years later. It’s important, and I’m really happy to see it happen because, frankly, a lot of the same big problems that were happening then are still happening now. It’s the same thing. Maybe they’ve got different faces or different labels, but they’re still messing people up. They’re still messing the world up. Nothing’s changed.

I don’t disagree with you, but I do find it incredibly discouraging.

But, if you don’t know there’s a problem, you’re lost. If you can at least say, “Yes, you’re right, there is a problem and this is it,” then you can attack it. Or you can at least get some other people together to commiserate.

When you recorded Spirit of the Golden Juice, what were your expectations for it?

When I recorded, I was being completely naïve about the record industry: “Okay, I’ll record an album and we’ll put it out. I’ll go around and I’ll play some places, then it’ll get on the radio and I’ll make a little money. Maybe I’ll record another album. I’ll make my living as a folk-rock singer.” It was really vague. That’s what I wanted to do, but I had no clue about how to go about it. To be fair, Accent was a small label and they didn’t have a clue about it, either. Their biggest star was Buddy Merrill, the guitar player from Lawrence Welk. So they knew how to market him. They marketed to the retirement homes and what not. They sold his 2,000 albums a year, and it worked great for them. But they didn’t have a clue as to what to do with Spirit of the Golden Juice.

Was there a moment when you decided to move on from music? Or was it more of a gradual decision?

Certainly. I had gone up and down the California coast for the better part of three years. I had played gigs at bowling alleys and bars, wherever. Somebody I was talking to said, “You should do Hawaii. There’s all this money over there, all these tourist bars.” So I went to Hawaii and played some hippie parties, which was fine. But in order to make a living over there, you have to go down to Waikiki and Kalakaua Boulevard, and you have to play the tourist clubs. You have to put on the white plastic boots, the white pants, the aloha shirt, and the plastic lei. You have to do Don Ho songs. That’s how you make enough money to pay the rent there, which I did for the better part of a year.

Finally one night, I’m on stage and I’m looking out at all the grandmothers in the audience. I’m listening to the ice cubes clinking in glasses and I’m thinking, “This is not what I started out to do.” I was done. That was my last gig. I packed up my guitar and that was it. I had gotten away from playing music that was meaningful to me and had turned into a human jukebox playing music for money, which took the joy out of it. The 450th time you play “Mustang Sally,” it’s no longer exciting.

Did you go back to this record? Did you ever listen to it after the ’70s?

I didn’t hear this record again until 2009. From 1970 to 2009, I didn’t listen to it. I had a framed copy on the wall, and my family saw it hanging there, but they never listened to it, either.

Did you relate to the songs differently after so long?

To be really honest, they felt like old friends. I fell right into it, after I remembered what I was doing and remembered how the lyrics went. It was wonderful. At the concert with Quilt, we did “Black Night Woman” and my God, that thing came out like a rolling avalanche. It gave me chills.

But the meanings of the songs were essentially the same, because they’re so strong in the first place. But one song stood out — “Five-Year Kansas Blues” — because there’s no draft anymore. The overwhelming feeling I get today is that all these kids who are going out to the far corners of the earth and getting themselves killed, they’re doing it because there are no jobs. That thought devastated me when I was singing that song. I wrote it 50 years ago about guys who went to jail instead of going to war. That was their choice. But now I’m thinking about the kids who can’t get a job, so they go into the Army and they get shot up. That’s not okay. So things haven’t changed very much at all. As a matter of fact, they’ve gotten considerably worse in a lot of ways. Back when I did the album, as bad as things were, kids were pretty sure they could go to college, get a degree, get a decent job, and have a career. They’re not so sure anymore.

Are you planning any more performances?

There have been some people making noise about it, but nothing concrete. I think it would be fun. I wouldn’t look forward to getting on a bus for three or four weeks, but I’d love to do the occasional here and there. If I ever get a chance to play with Quilt again, I’d do it in a heartbeat. Other than that, I suppose what I’d probably have to do is sit down do some serious reworking and work out some kind of solo set. But that could be fun, too.