“I think I found my way.”

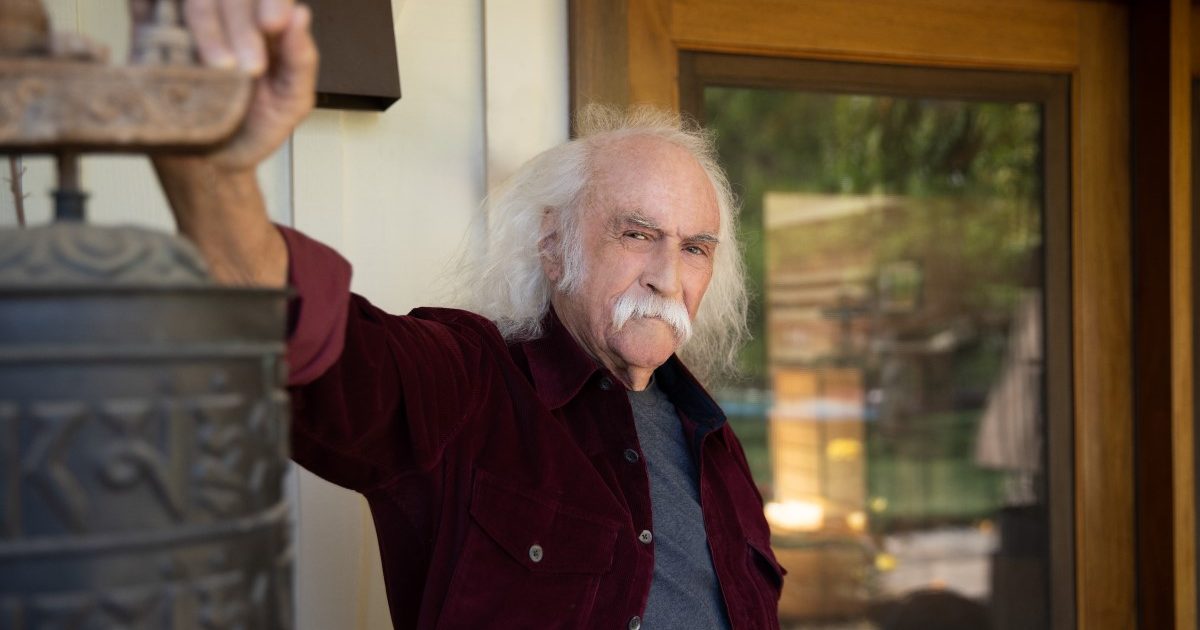

When a guy about to turn 80 sings that line, you take note. When that guy is David Crosby, who in fact turns that age on August 14… well…

“I don’t know if I would have sung it at any other time in my life,” Crosby says in a Zoom chat from his home north of Santa Barbara, California, where he lives with Jan Dance, his wife of 34 years.

But sing it he does, in the song “I Think I,” a highlight of his new album, For Free. With this, his fifth album in seven years (after just three solo albums in the earlier part of his career), he comes to his 80th in a remarkable creative run. It’s a strong collection featuring the fruits of several creative collaborations, mostly with his son, James Raymond. Among the guests are Michael McDonald on the shining opener “River Rise,” Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen on the jazzy, dark “Rodriguez For a Night” and Sarah Jarosz, with whom he duets on a gorgeously spare version of the Joni Mitchell song that gives the album its title.

It’s that line from “I Think I,” though, that speaks most profoundly to the state of his life. If you know much about that life, you understand. And you might greet those words with a sigh of relief. He certainly does.

“I do feel happy now,” he says. “The thing I love about the song the most is that it’s up. It’s, you know, happy sounding. Normally I record tortured ballads that go on for days. ‘The dog died’ or ‘my truck broke down.’ This is up and happy and positive and it just captures that mood that’s around. That’s a blessing for me. That’s a great thing.”

The life leading to this moment has been well-documented and much discussed. Most significantly, Crosby created some of the most bracing, beloved, and enduring American music of the past 60 years, first as a founding member of folk-rock pioneers the Byrds and then in the various partnerships with Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and/or Neil Young. Along with the essential, indelible songs CSN(&Y) gave us, there was much discord and discontent and it finally blew up, apparently for good, in 2014, sparked in part by some unfortunate remarks Crosby made regarding Young’s personal life. And Crosby’s history is marked by his years of drug addiction and a consequent prison term and liver transplant — and, thankfully, recovery. This was all covered in Remember My Name, the unflinching 2019 documentary that brought him to some painfully heartfelt reckonings.

For better or worse, Crosby’s legacy is tangled up with groups and partnerships. Asked to untangle it, he turns thoughtful.

“A lot of the musical complexity and strangeness comes from me loving jazz and world music,” he says. “I mean, I like a lot of different kinds of music, man. I like bluegrass. I like blues. I like classical music. And that has influenced me very strongly. Particularly jazz, and particularly jazz keyboard players, McCoy Tyner, Bill Evans, people like that. They have had a very strong influence because they played those real dense, big tone, cluster kinds of chords. And I couldn’t do them in regular tuning on the guitar. That’s what made me start re-tuning the guitar into other shapes so that I could get those kind of chords. So the jazz thing really did stack me up differently.”

That influence has been a constant facet, all the way back to the Byrds (“Everybody’s Been Burned” is almost a template for the folk-jazz explorations Tim Buckley would make) and CSN (“Guinnevere,” with its floating harmonics, was covered by both Miles Davis and jazz flute player Herbie Mann).

These days Crosby is not focused on the past, although with last year’s 50th anniversary of the CSN&Y album Déjà Vu and the expanded deluxe reissue, he’s had to do more of that than he’d like.

“I always prefer when it comes to talking about me, I like it to be somebody else doing the talking,” he says.

He’s not focused on the future, either. He says that he likely won’t tour again and with tendonitis in both hands, he expects he won’t be able to play guitar anymore within a year — a great shame as his guitar playing, with its intricate jazz voicings and inventive tunings, is as stunning as his singing, if not as widely recognized.

He’s certainly not looking forward to his birthday.

“No, no, no, no, no, no, no!” he insists. “Birthdays are not happy when you get old. No, no, no, no, no, no! We don’t celebrate. We mourn those.”

Yet he’s utterly bubbly celebrating the new album, as well as the four leading up to it, by far his most prolific stretch in terms of making and releasing his own music. It’s not often that we can say that about someone’s 70s, let alone someone with such a vaunted career packed with songs and albums cherished dearly by millions.

“Isn’t that weird?” he says. “It’s just completely bass-ackwards. But there you go.”

To what does he attribute this?

“I got out of CSN,” he says, never one to mince words. “It was, obviously, a wonderful band and we did a lot of really great stuff. But when it when sour, it went really sour. And it went sour very fast.”

It was rough, but the silver lining shines brightly.

“I don’t make anywhere near as much money,” he says. “But I’m making good music. And that’s kind of what they put me here to do, I think.”

Cue the title song, Mitchell’s loving portrait of a street musician playing for the pure joy of it. This is the third straight Crosby album to include a Mitchell song, following “Amelia” on 2017’s Sky Trails and “Woodstock” closing 2018’s Here If You Listen. Crosby, who was an early champion (and romantic partner) of Mitchell’s, producing her debut album, Song to a Seagull, sang “For Free” on the Byrds’ 1973 reunion album. Now, though, it has a deeper resonance, reconnecting to the essence of music-making. Rather than an observer, he’s the guy in the song.

“Yep,” he says. “There I am standing on the corner. It’s squarely, smack dab in the middle of who I wanted to be, as me. I love what it says. Putting it on as the title track is also taking a little dig at the streamers. Because it is for free, man. They don’t pay us.”

Crosby had become a fan of Sarah Jarosz via I’m With Her, the group in which she’s teamed with Aoife O’Donovan and Sara Watkins. And he loved Jarosz’s 2020 album, World on the Ground.

“I called her up and said, ‘Listen, Sarah. Can we do something together?’” he says. “And she said, ‘Sure! What do you want to do?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know. I just want to sing with you.’ And she said, ‘Oh, you sweetheart.’”

Crosby quickly suggested “For Free.”

“I’ve sung it a bunch, and I’m confident with it,” he told her. “She said, ‘Oh, I love that song.’ So I sent her a tape of it that I went in to the studio and cut. James made this incredible piano track for it. Just beautiful. Sarah sent it back with her vocal on it, and it completely blew my mind out of my ear. It was unbelievably good.”

Clearly, Crosby still craves collaboration. A sense of joyful purpose is unmistakable in his voice and in the voices and playing of those who helped him make the album. Foremost is James Raymond, the producer-composer-keyboardist who has been at Crosby’s musical side regularly since 1997, five years after learning that Crosby was his biological father. His talents have been showcased not only in his father’s solo projects, but also for years with CSN as a full-time member of the touring band, and in the jazzy group Crosby and Raymond fronted off and on with bassist Jeff Pevar, cheekily branded CPR. On For Free, Raymond wrote or co-wrote seven of its 10 songs, including “I Think I” and the somberly beautiful closer, “I Won’t Stay for Long,” inspired by Marcel Camus’ haunting 1959 film Black Orpheus.

“It’s wild to watch,” Crosby beamed. “He’s gotten to be as good a writer as I am, or better. ‘I Won’t Stay for Long’ is the best song on the record. It makes me cry. It just freaks me out.”

Guitarist Dean Parks adds color to “Rodriguez” and “Shot at Me,” the latter a powerful ballad which he co-wrote from Crosby’s words inspired by an encounter with an Afghanistan war veteran, who told him of the most human costs of war. It’s a strong addition to Crosby’s deep catalog of incisive, biting topical songs.

“I seem to run into those guys and talk to them,” Crosby says. “I ran into this guy at the airport and was drinking in the bar and he looked really bummed, really sad. So sure, I talked to him.”

As for not being able to tour anymore, Crosby is sad but sanguine.

“Singing live is the great joy of my life,” he says. “My family and singing live. That’s the top of my world, you know?”

Even if the shows stop, the music won’t, right?

“I don’t know,” he says. “I can still sing. That’s why we’re doing the records, because we love making music. Right? They obviously don’t pay us for them, so that’s the only reason there could be. We’re not trying to win the ratings war or something. We’re just singing exactly the music that really rings our bell and makes our heart sing. And there you go. And if people like it, great. And if they don’t like it, great, we don’t care.”

Photo credit: Anna Webber.

Album cover painting by Joan Baez.