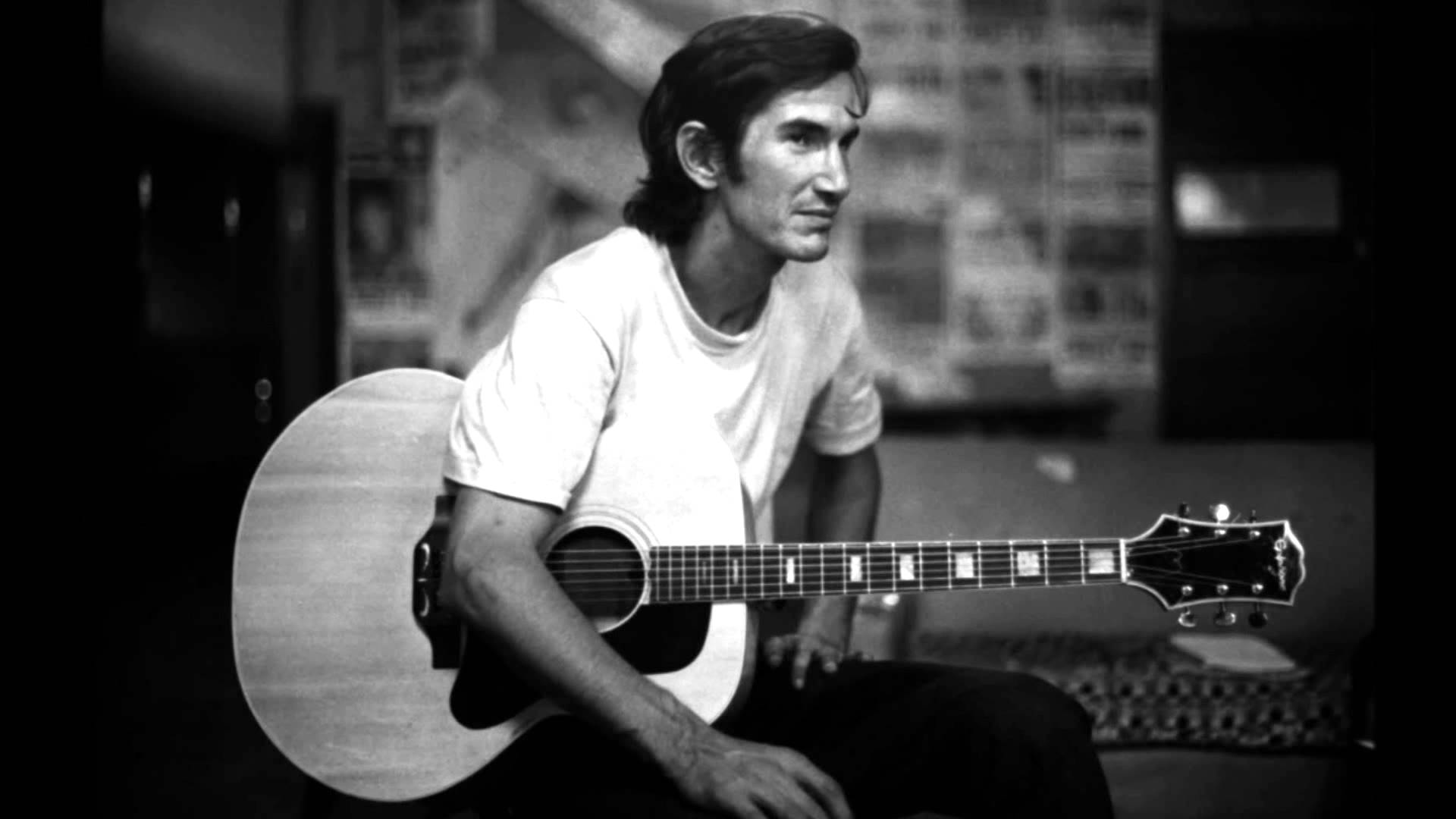

“Townes Van Zandt’s the best songwriter in the world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that.” — Steve Earle

Agreed, Mr. Earle.

By now, Steve Earle’s devotion to and admiration for Townes Van Zandt are fairly well-known bits of music history. Earle used to carry Van Zandt’s guitars around for him. What isn’t so known is Van Zandt’s response to the notion that he was a superior songwriter to Dylan, or that such a comical gesture such as standing on Dylan’s furniture could be accomplished: “I’ve met Bob Dylan’s bodyguards, and if Steve Earle thinks he can stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table, he’s sadly mistaken,” was Townes’s pragmatic reply.

An indispensable book for any Van Zandtian is To Live’s To Fly, a remarkable, lyrical effort by John Kruth with the subtitle “The Ballad of the Late, Great Townes Van Zandt.” It’s a book in which Kruth’s abilities rise to that of a very good fiction writer, as if [add your favorite Southern novelist] had turned musicologist and journalist writing the tumultuous times of the mythical and legendary Van Zandt. Some of the stories about Townes certainly seem part legend, part myth. Like the time Townes was attending university in Boulder, Colorado, and deliberately fell from a high balcony and plummeted, Icarus-like, to the earth in order to see how it felt. Or the time Townes was (finally) to go on tour with Lightnin’ Hopkins — one of the former’s heroes — but got drunk and flew out of a manic-paced pickup truck and broke his arm, making the tour insurmountable.

Kruth’s book is filled with interviews, stories, and anecdotes that all weave together to make something gorgeous, and his prose sometimes makes one want to give up and write at the same time, to make little efforts in crafting better thoughts and sentences. Good luck.

What little I know about Van Zandt — from his hard living, habits and addictions, and mental disorders — I have learned from Kruth’s masterpiece. What I actually discovered about Van Zandt on my own, which may be the experience of so many other souls, comes from daily attention to his songs which, in the end, are mysteries in themselves. Van Zandt’s tunes call one back and back again.

Take “Waitin’ Around to Die,” the first song he wrote, crafted in a tiny closet shortly after his marriage to his first wife, Fran. It was made just around their honeymoonish salad days, and the song speaks to the darkness that resides in so many of us, though we mask it in a variety of frivolous or sincere or even actively destructive ways. Needless to say, the song frightened Van Zandt’s wife.

At the time of filming, several musicians and friends of the unparalleled troubadour expected him to be living in a reasonable house and better situation. Instead, the scene is one of squalor and drunkenness, yet Townes performs perfectly, in spite of copious amounts of whiskey and generous allotments of poverty. We follow the singer into a tale of wife-beating, robbery, and addiction, difficult subjects to broach with one’s new bride who simply didn’t see those sorts of bleak — albeit beautifully and well-made — sentiments coming from hubby.

“And I am in retirement from love …” — William H. Gass

“’Fare Thee Well, Miss Carousel’ relates a tale of bitter disappointment in intricate wordplay and metaphor, with a twist of spite that sounds inspired by Dylan. In a mosaic of images and seemingly disconnected events, Townes lays the guilt of another failed love affair at the feet of a fickle woman.” (Kruth, pg. 110)

Kevin Eggers signed Townes in 1968, and recorded and released the bulk of the musician’s work. To this day, controversy and legal battles still rage around the rights to Van Zandt’s music. It is as if the songwriter — who pushed himself through addictions and hardships to craft some of the greatest songs ever written, who was known for his hatred of money, who was concerned with the next gig, the next inspiration, the next vision and tune — isn’t free even after his release from this world. We second Guy Clark’s response to queries about Van Zandt’s royalties and estate: “That’s none of my damn business,” said the normally loquacious and articulate Clark in an interview with The Austin Chronicle in an interview. Agreed, Mr. Clark.

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” Leo Tolstoy wrote in one of those impossibly thick Russian novels that draw the reader in and, in the end, make him or her wish the book had been even longer. The same wish might apply to Townes’s discography. From recorded live shows to studio albums, one cannot get one’s hands on enough of his music. It’s the feeling — at least when writing an article or piece about the singer/songwriter — that one’s own efforts are false, useless. Each word and eventual sentence is swallowed whole by Van Zandt’s songs, lyrics, life.

When researching his life — from legal battles over music to his nearly cursed inability to have a long-lasting relationship with a woman to falling from that balcony — anything added now rings hollow and pointless. Townes is and was as good or better than Dylan.

I imagine Townes landing after that fall he deliberately took. I imagine him smiling and brushing himself off, and finally standing on some table of his own, singing through a golden room. I imagine him happy, finally, and letting his music also stand on its own. Townes was a body and mind tuned into something inaccessible to most. Call it a god, a form, a preternatural gift that few understand or know of. Call it the songwriter’s knack for falling and, like the mythical Phoenix, rising out of the ashes, rising from the ground, and letting the voice bell and resound against all odds.

Townes had that, whatever that is.