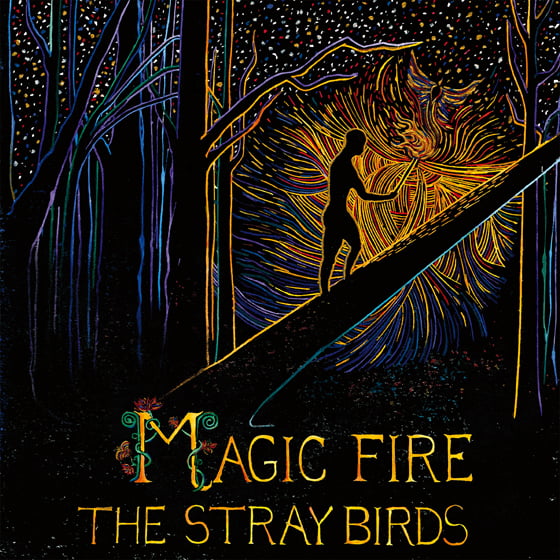

The Stray Birds could have kept everything the same about their sound and their process and still have made an incredible record. The band — which revolves around members Maya de Vitry, Oliver Craven, and Charles Muench — had already hit number two on the Billboard bluegrass charts with their YepRoc debut, Best Medicine, in 2014, garnering praise for their rich harmonies and swift picking while building a name as songwriters, too.

But for the forthcoming Magic Fire, the Pennsylvania-based group willfully took steps in a different direction — not toward a different sound, but rather a growth from the straight-up string band they started with. Dabbling with a new percussionist and collaborating on songwriting in a new way, the band brought in Larry Campbell, the genre-jumping instrumentalist whose work specifically with Levon Helm and Bob Dylan made him the Stray Birds’ top choice for their first record with an outside producer. What resulted was a 12-song collection of commanding vocals led forward by a deftness on the strings that can only come from a tight-knit group that loves to play together.

This album was a new experience for you guys in terms of the way it was recorded. Tell me about the decision-making when you were gearing up for this album. Did you have any specific goals in mind?

Maya de Vitry: We have always been a trio, a string band, trying to explore playing songs with string instruments. That’s the texture that we started out with — it’s what we were comfortable with, it’s what we knew. But it’s not the only sound that we love, and it’s not the only music we listen to; that has certainly never been limited to string bands, and certainly never been limited to those textures. When we started to get the songs together for this new record, it overlapped with us finding a percussionist who we were interested in recording with for the first time. We were never sure what instrument it would be that would pull us in the next direction, or who that person might be, or what the sound would be. But we met Shane [Leonard] and, as we were putting this new record together, we started to think about having drums on it — a more electric sound.

So we started putting those songs together and thinking about the person who might help us build that bridge. We thought that it would be somebody like Larry Campbell. I’d seen him perform a few times with Levon Helm’s band — he was the musical director for that — and I was familiar with some of [Campbell’s] work with [Bob] Dylan. Always it seemed like he was arranging music to really fit the song and to really communicate. Larry could live in all kinds of musical worlds, and we were excited to see what he thought. There were no limitations with what kinds of sounds we could paint with these songs.

Is there anything in particular that you’re most proud of now that you've tried something new?

I think this was our best singing on an album. I think we were relaxed, and we were inspired by Larry’s presence. We felt comfortable with him, and our singing, in particular — some of the phrasing, the tone, and the inflection that we have — I’m really proud of. It’s more free than it’s been in the past, and I’m really excited about that.

I’m really proud of the song “Mississippi Pearl.” It’s kind of tucked into the back of the record, and it’s the only waltz. But it didn’t start out as a waltz. It was in 4/4 time, and a totally different feel as a song. I was never totally in love with it, but I had the words and I had the melody and the chorus, so I had it on the table as a song that was possible to record. I wanted a waltz on the record and we didn’t have any, so Oliver suggested we turn that one into a waltz. Larry heard something in the melody of the song, the way that it opened up. It became much more spacious as a waltz. The story of the song fit better in that new feel. Larry heard something in the melody and wrote this whole melodic hook, this instrumental thing, and he just wrote this whole new part of the song, an instrumental bridge, right there in the studio in front of me. It was a new experience for me, to be open: to have this thing, and I don’t love it — yet — and for him to hear it and be like, "This thing that you don’t love yet? Listen to this idea." So Larry was my co-writer on that song and, in that moment, it was so inspiring. It’s like something cracked open — all of the ideas were available. The song lives as a waltz, and that’s the way it was meant to be. I couldn’t find that on my own.

You said something earlier about painting sounds, which brings me to another question I had about the album art. What inspired you to create that yourself?

I had no plan to do the artwork up until we got into the studio and we got inside of these songs. We naturally started talking about what we could possibly call the record. We wanted to find some words that captured the spirit of it without lifting them specifically from a single song. We didn’t want to have a title track; we just wanted to have a concept of a title. I sort of started dropping the idea to people that I might want to do a painting or some kind of cover art, but I really didn’t know how far into it I wanted to get, at that point. We were basically trying to find something to represent this music other than the three people who wrote it. [Laughs]

We finally came up with the name, which really drove the art forward, when Oliver and I were hanging out with his dad back in Pennsylvania, right after we had finished recording. We were just up late making nachos one night, and he was joking about how all you need to do to make nachos is to wave the magic fire stick around. My ears had been totally open for any word that someone was saying that could possibly fit for the title of this record — I wanted it to feel like it was kind of out on a limb, like it was up to the listener to build a bridge between the songs and the title. So we put the music on right away, the super-rough mixes, and we just listened to the whole thing in the kitchen.

We started drawing our own connections from those words, “magic fire,” to each individual song: “Oh, in this song the fire is love — it’s chemistry.” “In this song, it’s literal fire.” We’d find different meanings in each song that could be connected to it. If not just fire, at least connected to something with the elements, or something very old. We liked the idea of that because this whole record is something very new for us, and it’s nice to feel that juxtaposition. For me, where I started to love music was sitting around a campfire and sharing songs with people. Today, the way that most people have their musical intake is through their phone or computer or the soundtrack in a movie or on the radio. Still, for me, the most alive that I feel is often around a campfire with people. I think it’s less and less about the audience, but about taking things away and remembering what you liked to do as a kid and remembering how fun it is to build a fire and to do new things. That’s kind of what we were doing with this record: playing with fire.

So you had all of these songs before the concept brought them together?

We had it all written and recorded. We had these mixes, and we wondered what could possibly capture them. Then, it became a question of what visual thing could represent these words. Some of them were written collaboratively, but some of them were written individually — in many different settings and times and frames of mind. It wasn’t written as a concept album, but I do think that the inevitability of change is a theme that is there. From the first track to the last track, it’s a theme on the record.

Speaking of the writing, together and separately, tell me about how all of that began.

We started playing music together in 2010. Oliver and I got started at open mics, and also we would play at the farmers' market here. We would go in, and there’s a market master who we would get permission from to play at one of the empty stands at the market. We’d just play for tips, buy a couple of Italian subs, and call it a day.

That was how I started feeling comfortable singing my own songs and coming out of that shell. I had been a fiddle player for a long time, but would not have called myself a songwriter much earlier than those moments, so that was a pretty recent thing for me. Charlie and Oliver had been playing together a little bit in a band, a bluegrass band. I would go and see those shows and see those guys play, it was like four guys playing bluegrass and some original songs of Oliver’s. When that band parted ways, we became a duo and got Charlie, who was in River Wheel also.

It started as just a collection of songs we were doing. The harmonies sounded pretty good to us, so [we thought] maybe other people should hear them. Maybe we could have a CD release show in an art gallery in our hometown. It was not a very sculpted vision.

But we played a festival. We went up to Michigan, to Bliss Fest. It was the first thing. Jim Gillespie, who runs Bliss Fest, heard our little EP of five songs that Oliver and I had made back in 2010, and he hired us to come play Bliss Fest. So we said, “Charlie, do you want to go with us?” So we tried to scrape together enough songs to have another couple sets of songs that we could play throughout the weekend. We just drove to Michigan and we got to play on all of these stages in this beautiful festival. We met so many nice people, and we started loving life and thinking, "Maybe we should be a band. We should play more festivals." I think that experience — leaving home, playing for strangers in this beautiful new setting — was intoxicating. We thought, "We could do this together." Bliss Fest was the moment.

You mentioned something that I’m always curious about: that transition from being a musician, someone who’s comfortable performing, to being comfortable with playing your own music. Was that an immediate switch for you?

I think it was just a moment. I think I was so terrified that people would ask me to explain where exactly the song came from or what I was thinking or who the song was about. Not that I was afraid to answer or didn’t want to answer — I didn’t even know if I could answer that. Songwriting, to me … I was figuring out that it was this really mysterious and really kind of unexplainable thing. It kind of felt like magic!

And I didn’t want to explain it. I just wanted the song to be there and for people to take it or leave it and just listen to it and live in it with me for a couple of minutes, and have as their own. I think that was my fear, though: that I would have to explain something that I didn’t know. When I started actually playing my songs, I realized that people didn’t necessarily ask. That wasn’t a part of the job. I was scared of something that I didn’t have to be scared of, and I could just let the song be its own thing. [I realized] that it was okay for the inspiration to be from my dreams and my experiences and multiple people. It didn’t have to all come from a traceable point, and that was the huge earth-shattering realization for me.