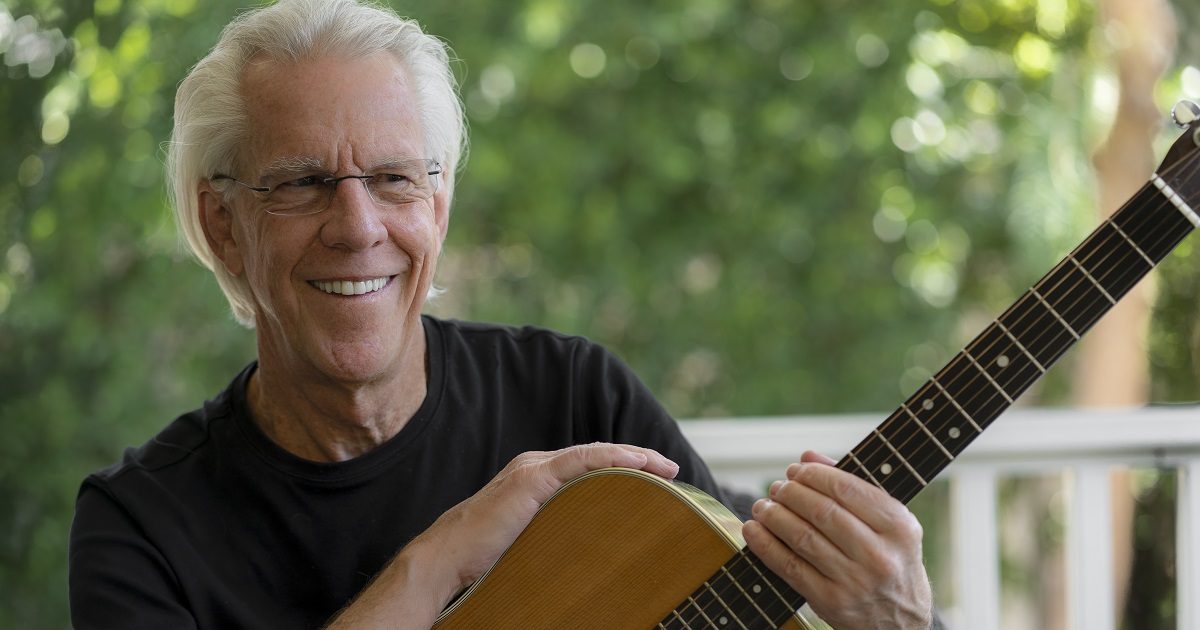

Jim Ed Norman has juggled all kinds of jobs over five decades in the music business, but he decided to get back to his roots after receiving a phone call from Don Henley. The two musicians met as college students in Texas, then briefly played together in a band called Shiloh. But it was their creative collaborations on a couple of Eagles records that stuck with Henley for all these years. When the offer was extended for Norman to lead the orchestra on tour as the Eagles played the entirety of their 1976 album, Hotel California, it proved irresistible.

By accepting the gig, Norman switched gears yet again — which is something he’s done throughout his career. Over the last 50 years or so, Norman has developed an impressive profile in the music industry, but not always as a musician. Along with his conducting and arranging work, he produced multiple albums for Anne Murray, served as president at the country division of Warner Bros. Records, and even started a “Progressive” division at the label, taking a chance on artists like Béla Fleck and Mark O’Connor. As a producer, he shared a Grammy win in 2021 with the Fisk Jubilee Singers.

Now he’s in the spotlight himself, particularly when the orchestra is revealed to the audience after just a few songs. To make the return even more poignant, the tour heads to Texas in May, where the long-standing relationship began. While off the road and working on his home in Franklin, Tennessee, Norman told BGS about how it all started.

BGS: This feels like a full-circle moment now that you’re on the road with the Eagles. What is your role out there?

Norman: Well, first I want to say it’s great to hear you use that phrase “full circle” because that’s exactly the way I’ve looked at it and thought of it myself. I did all of the original orchestral arranging and conducting for the records for the Eagles, beginning with Desperado through Hotel California. Then I also played piano on some of the records through the years. I got a communication from Don Henley, whom I’ve known a long time, saying the band wanted to mount a Hotel California tour. They do the album top to bottom — and they don’t say a word in between.

When the album came out, it was on vinyl, and the A-Side ended with a song I was moved by emotionally, and what was going on with it artistically, and the quality of the songwriting. Don and Glenn were just amazing writers. So, I wrote an orchestral-only piece. Not per their direction; I was just simply moved by it. It happened that the day we were in the studio, we got finished and had some time left over. I said, “Hey, guys, I wrote this orchestral piece. Would you be interested in me sharing it?” And they said, “Yes, that sounds great.” So, we ran it down and recorded it.

Then they called me sometime later – or I don’t know if they even called me. I might have found out when the album came out, but Side A ended with a song called “Wasted Time” and Side B opened with “Wasted Time (Reprise),” the orchestral-only piece. So, when Don called and said they were going to mount this tour, he said, “Jim Ed, you can do whatever you want [on the tour] because we’re going to be doing your charts.” The more I thought about it, I decided to quit the day-to-day to reconnect with the creative process, if you will.

This was an opportunity, as you have outlined, for the full-circle aspect. It was how I started — as an orchestral arranger and conductor. The work with the Eagles led to doing it with Ronstadt, Seger, Kim Carnes, and America, and other people. On Hotel California, the orchestra comes and goes, and I do get an opportunity now to hear things I wrote so many years ago, lived out in that kind of environment. … The encore section includes “Desperado,” and “Desperado” was the first orchestral thing I ever wrote. I was fortunate that it ended up on such a great song and connecting with such a great group of guys. Every night on tour, I get to hear the arrangement that started it all for me.

Do you remember your response to first hearing the lyrics to “Desperado” and what it meant to you at the time?

It was around 1972 or 1973, when the music was being formed and “Desperado” was being written. So, the guys put together a demo for me. It had a lyric that went something like, “Desperado, da-da-da, da-da your fences, da-da-da-da… for so long….” The lyrics weren’t quite formed but it had a wonderful melody and structure. So, I first heard it in that form. The guys then went to London, where they were working with Glyn Johns producing. They sent me the track that they had recorded on reel-to-reel tape. I then got to hear the finished song, and I remember thinking this is wonderful because it’s also somewhat the linchpin conceptually of the record. The conversations that I heard at the time from Don, Glenn, and maybe Jackson [Browne], I knew there was a connection between life on the road and the life of an outlaw.

It’s easy to look back on it and conjecture, but I know Don well enough to know that little was left to chance. Don and Glenn were very thoughtful and insightful artists and songwriters. The other thing that was great about the experience is that was the first song Don and Glenn wrote together. And to think of that kind of eloquence, and what it says… It became a touchstone for me in my life as an arranger, because in all of my work subsequently, it was about putting emphasis on the lyric. It’s not a matter of showing how many notes you can write. (laugh) But rather frame what was going on, so that you listen to the vocalist intently. Then you have a melodic fill to keep your ear in tune with what the singer is singing.

All of the lyric content of the song was a very strong motivating factor in the notes that got written. There’s one lyric – “There’s a rainbow above you” – where I had specifically done this soaring thing. Whether anybody else ever thought of that as a rainbow, I’ll never know. I bet I listened to that version they sent me probably two to three weeks, or a month. I did nothing but listen to that song over and over, for weeks! At a certain point, I would even dream it, and imagine the orchestral things that would be going on around this song. One day I got the paper out and I ended up trying different things with a complement of instruments. In an orchestra, you have first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses. And I actually had no violas in this section that was used on “Desperado.” It was nothing but violins, cellos, and double basses. And it was with the idea of having a depth and “guts” with what was going on with the orchestra.

You mentioned that when you were arranging “Desperado,” you were listening closely to the lyrics. Did that come in handy as you started as a producer in Nashville? So much of the work you had to do was centered around lyrics.

Yes, I think so. I grew up with instrumental music as a young child. The first thing that I played, in the fifth grade, was trumpet. Then I moved to piano lessons for six months, and moved on to another instrument, and another, and another. Most of my early life was as an instrumentalist. A lot of the music I heard in the landscape of the ‘60s, you had the orchestra happening. … Even on the Beatles records, right off the bat, you’ve got a producer like George Martin, and I was swept along and magically transported by what I was hearing musically and orchestrally. When I say “orchestral,” in many cases I’m talking about how the Memphis Horns were just as cool as the London Symphony Orchestra.

It was in the mid to late ‘60s when I began to realize, well, there are lyrics here too. And how, at times, those things meld so perfectly that your emotional response to what was being said was because of the support that was happening from the complement pieces other than just the band. To me, I thought the Beatles were a good four-piece band. Those guys sat down and rehearsed and practiced and they were really good, but occasionally the songs had this additional complement that made the song special. There was a recognition that was beginning to happen for me about the power of lyric, and that grew and grew and grew through that period. I would say, without a doubt, it began to crystallize in my exposure to the work of Don and Glenn and Jackson and J.D. (Souther). It changed my perspective on what lyric was, and the importance of the lyric and the music combined.

Photo Credit: Paris Cronin