In her four-part series Sitch columnist, JEWLY HIGHT, explores the the ties between rhythm & blues and the roots, Americana and bluegrass music world.

Perhaps you’ve heard the blogosphere buzzing over the fact that one of the biggest acts in electronic dance music, the French duo Daft Punk, felt the need to build their latest album upon the performances of real, live musicians — as opposed to mechanized programming — in pursuit of “the soul that a musician can bring.” Something else that recently got my attention was a quote from Bradford Cox, the white lead singer of Deerhunter. In an interview about his band’s new album, he diagnosed indie rock as lacking “Bo Diddley and blackness,” as well as the “struggle” of “hillbilly music from a certain era.” Then, too, one of the more striking R&B music videos I’ve seen of late is a dystopian sci-fi fantasy from the ever-imaginative Janelle Monae. While these bits of pop culture might not seem all that significant on their own, I’ve come to interpret them as outside confirmation that something big is going on in that bastion of realness — or “realness,” if you like — that we know as roots music.

It wasn’t lost on me that a young neo-soul-influenced singer-songwriter named Chastity Brown showed up to play a showcase at last year’s (2012) Americana Music Festival in Nashville. Or that the weekly live and radio stage show Music City Roots has been playing host to more and more twenty-something bands with horn sections and a penchant for boogieing down. Or that this year’s (2013) Grammy Awards featured an all-star tribute to Americana hero Levon Helm and a host of other recently departed music makers, in which the Alabama Shakes singer Brittany Howard held her own next to flamboyant elders Mavis Staples and Elton John.

With mainstream R&B now deep into its futuristic phase, much of current rock, indie and otherwise, devoid of roll and dance music’s pace-setters searching for a flesh-and-blood pulse, performers of a new generation are gravitating toward roots music and bringing with them more physically robust forms of expression and a revival of rhythm and blues ingenuity.

Before and after Bonnaroo, I’ll be exploring this trend in a multi-part series, looking at how acoustic music has helped open the door for this, as well as how young performers are expanding on tried-and-true Americana models for singer-songwriters and roots rock bands and toying with new ways of embodying their identities.

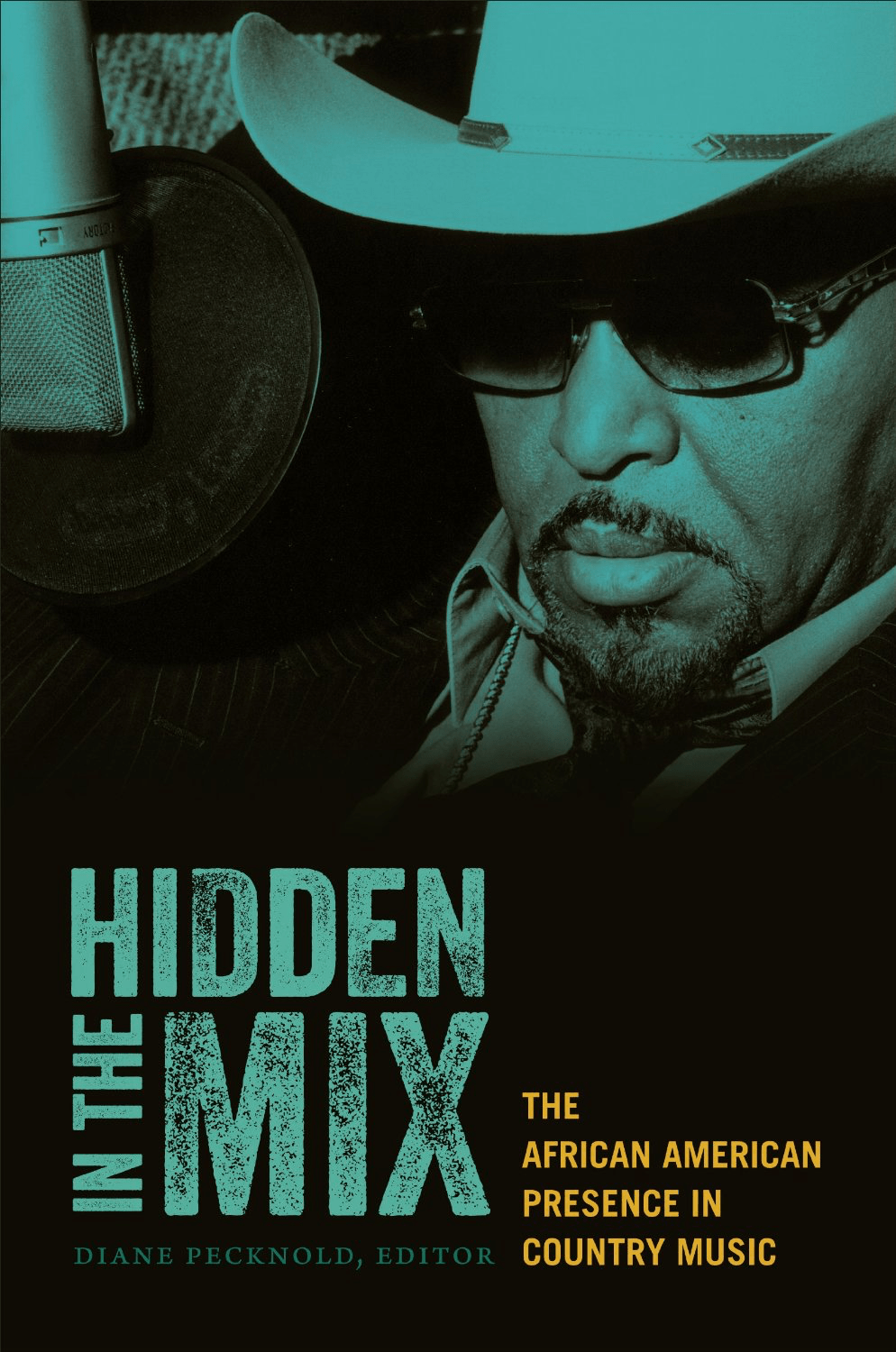

First, though, it’d be helpful to unpack the history of our thinking about who plays what music and why. The tangle of racial, stylistic, social and commercial factors is far too complex to tackle in a six-minute song, though Brad Paisley (maybe?) deserves credit for making the attempt. But from Tony Russell’s Blacks Whites & Blues to Karl Hagstrom Miller’s Segregating Sound and a very important new book edited by Diane Pecknold, Hidden In the Mix: The African American Presence in Country Music, there’s illuminating scholarship on the subject. Here’s part one of a phone interview I recently conducted with Pecknold.

You couldn’t possibly have anticipated, when Duke U Press settled on the release date for the book, that something else would happen to stir up conversation about race and country anew.

Diane Pecknold: Are you talking about “Accidental Racist?"

I am! Even outlets that don’t usually pay any attention to country music covered it, and so much of the coverage had little or no sense of context. I wondered if you might take that as an indication of how important this book is at this moment.

I was really interested to see the difference between the way people who don’t normally pay attention to country music or like country music wrote about it versus those who I think would identify themselves with country music wrote about it — even though they would not identify themselves with some of the problems the song raises. I think having some more, as you say, nuanced way of talking about the effort to deal with race in country music is, you know, I hope the book will advance that at least. I don’t know whether it will or not, but I do hope it will. I was really struck by the way people who do not apparently think about country music a lot assumed a lot about who [Brad] Paisley was prior to releasing the song, and assumed that Paisley was speaking for himself in the voice of the song’s character.

I kept hearing people talk about it as an autobiographical song, but I wonder if his personal perspective isn’t more sophisticated than that.

Yeah, exactly. I saw it as him in the time-honored tradition of country songs taking on a character and speaking from that character in very mundane ways, from that character’s point-of-view.

I think it’s significant that he made the attempt, and was trying to speak to the country audience in a certain way, even though the execution is … [laughs] And I’m hoping it’ll make for a receptive audience for the book.

I hope so too. As the introduction says, it’s kind of a paradox that on the one hand, country music is white. I’m not trying to argue that it’s not coded as white music or that it doesn’t function as white music in our culture. But there is also, undeniably, a longstanding tradition of African-Americans either just flat-out playing country music or engaging with it and using it in other genres. How do you resolve that? What does it mean that it manages to stay white even while it’s being used and engaged with by African-American artists and entrepreneurs? I don’t know.

Patrick Huber’s chapter emphasizes the artificial nature of commercial categories like “race” and “hillbilly,” and talks a lot about how those designations didn’t seem natural or self-evident at the beginning and were developed through on-the-fly marketing decisions by record companies, sometimes based on narrow assumptions about who the audiences were for this music. Why do you feel like that kind of contextualizing is important? What kind of difference do you think it could and should make to the interpretation of what’s going on in the contemporary landscape?

I think one of the things [Patrick Huber] does so very well is to outline this pretty robust habit of totally disconnected African-American old-time records and interracial old-time records, so you can’t argue that it’s one scene or one locale producing these recordings. This is clearly a really widespread set of traditions that are bubbling up in these recordings, but that are hard for the A&R guys to figure out just quite what to do with. And I think the other thing that’s really interesting is the degree to which it didn’t always hinge on race. I mean, [the] received wisdom [is] that, “Oh, categories like hillbilly and race, and the racialized categories that followed from those, those were conceived of. It was impossible for people to imagine anything outside of that dualism.” But clearly, the people that he is looking at did imagine things outside of that dualism. They did experiment around and apply other logics.

So I think on the one hand, it does tell the story of why race played such a critical role in defining country music as a genre, but on the other hand, it also points to all of the opportunities or the little fissures in that racialized genre ideology that I think people can still see today. I think it kind of strikes a nice balance between recognizing the way that whiteness and country music came to be associated with one another and the possibilities for other outcomes, that still remain open.

In the chapter after that, you explain that at the time when Ray Charles released Modern Sounds in Country & Western Music, it was championed as a sign that the country audience was sophisticated and upwardly mobile, but the race piece of it wasn’t engaged nearly as much. You draw a contrast between the fact that people concluded there was an audience for the blended, hybrid thing Elvis was doing early on and the fact that they didn’t draw the same conclusion from Charles’s album. Could you talk about why this countrypolitan album by a black soul singer was interpreted so differently from those early rhythm & blues and rockabilly sides by a southern, white kid?

I wish I had a really good answer for the why of that. I think part of it certainly had to do with racial privilege, that it’s always been easier, historically, in the music industry for white people to borrow stuff from black folk and become popular with it than has been the reverse.

Maybe one of the things was that by the time Elvis became who he was and sort of represented this crossover/fusion of white and black music, he was not the only person doing it, right? There was an infrastructure essentially of people who were already interested in that particular form of crossover, so that to see him as part of an emerging genre was realistic, because there were others doing the same thing. That territory had already begun to be defined in some way.

Ray Charles was not the only person doing what he was doing. Solomon Burke had also started to do the same kind of thing. But there were far fewer people doing it. And after Ray Charles did it, then I think, to some degree, a lot of what happens as country soul in the later 1960s is informed by the popularity of that record. But I think given that country radio didn’t play it and it wasn’t really embraced by R&B radio either at the time, until it became really popular, there was not an infrastructure, a circuit of stations and labels and those kinds of things that would make him the figurehead of a particular [movement]. In Elvis’s case, he was making something that was already there, far more visible, whereas Ray Charles was not the figurehead for a movement.

So I guess to some degree what I’m saying is the industry was kind of right in thinking that it did not constitute the same thing, because there wasn’t as much underneath him as there was underneath Elvis. But I also think that part of the reason there wasn’t as much underneath him was because of the racial imbalance in the music industry.

I was going to bring up Solomon Burke. You talk in that chapter about him recording country songs during that era. Of course, much later in his career he came down to Nashville and made an album literally titled Nashville with Buddy Miller. On it, there’s material from Tom T. Hall, Buddy and Julie Miller, Gillian Welch, Dolly Parton.

That’s a great record. I love that record.

I remember when he performed at the Americana Music Festival and was the subject of long features in No Depression magazine. He was, on some level, getting recognition and respect from an Americana audience. What would you say is the difference between how he went about it and was received then and what had come of him recording country songs like “Just Out of Reach” and “Detroit City” decades earlier?

Maybe this is the elephant in the room, but the truth is that for all of the totally accurate emphasis on collaboration across racial and genre lines in the music scene in Nashville, I think it is also the case that racial attitudes just had shifted between those two periods … Solomon Burke tells a hilarious story in that Peter Guralnick book Sweet Soul Music about getting booked to what turned out to be a Klan rally, because nobody realized that he was black … Part of it also is a change in the way that artists are presented and marketed. An artist in 1958 could be just a song on the radio, and on that basis could be booked into a venue, whereas now, all of that supporting material, in terms of music criticism and media coverage and all that kind of stuff, you’re never gonna end up in the Solomon Burke situation where you show up and they didn’t realize your race before you walked in the door. I think that is one thing. The actual shift in racial attitudes is another thing.

That makes me think of the famous story of Charley Pride’s first country single being released without a photo.

Exactly. I also feel like things have changed a little bit in the sense that there is an emphasis on hybridity and combination now that there kind of wasn’t then. So if you just take what people said about Solomon Burke’s first single, as they were with Ray Charles, the labels and the A&R guys were really worried: “How are people even gonna respond to some black guy singing a country music song? The R&B people aren’t gonna like it because they’re not gonna get it. The white people aren’t gonna like it because,” A&R label guys assumed, “they’re racist. So who the heck are we gonna market it to?” I think now there’s much more of a premium placed on hybridity, crossing genre lines, putting things together in new ways, just because that’s kind of the cultural atmosphere now in a way that I think maybe it wasn’t then.