In 1978, during a concert on the White House lawn, legendary jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie put the leader of the free world on the spot. President Jimmy Carter, formerly a peanut farmer in his home state of Georgia, had requested “Salt Peanuts,” a rambunctious tune that had been a hit for Gillespie back in the 1940s, but the musician said he’d only play it if Carter himself sang the lyrics. That’s not a hard job: There are only two words, “Salt peanuts,” repeated over and over, in a fast, staccato exclamation.

Carter gamely obliged and took his place onstage among the jazz greats, wearing not an official suit but a more casual outfit of unbelted slacks and a shirt-sleeve shirt. No musician himself, the President gave it his best shot, but could barely keep up with the veteran players. The song ended in laughter, but it was no joke. Instead, it revealed not only Carter’s sense of humor about himself—a rarity among politicians—but also his abiding love of music. Even as he’s flubbing such a basic vocal, he looks like he’s having the time of his life up there.

That impromptu performance is a key scene in the persuasive and often joyous new documentary Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President, which redeems the 39th President by examining his accomplishments in office through his relationship to music. The words stagflation and malaise are never mentioned, nor is there any appearance by an angry rabbit — all issues that have long obscured Carter’s legacy. A naval submarine officer turned politician who farmed peanuts on the side, he served in the Georgia State Senate through the 1960s before running successfully for governor in 1970.

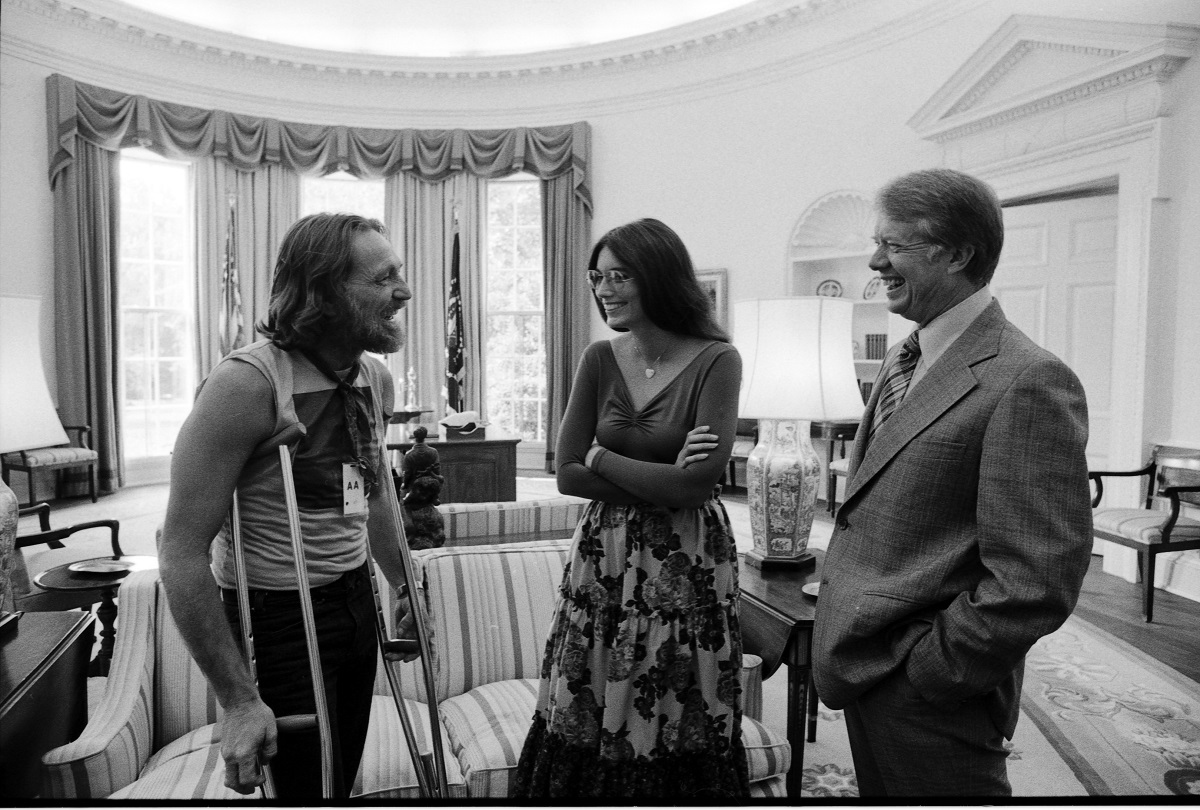

Six years later he ran for president, right at the heyday of southern rock and outlaw country, when the entire nation seemed to be fascinated by the South. Artists like Gregg Allman, Ronnie Van Zant, and Willie Nelson saw in Carter more than a little of themselves: Southern men who didn’t fit the old hick stereotype, who might have called themselves rednecks, but rejected the hostilities and prejudices and buzzcuts associated with that figure.

And Carter was a real fan of the music they were making at that time. They not only befriended but endorsed him, playing fundraisers along the campaign trail and later visiting him in Washington, DC. Willie Nelson was famous for sneaking up to the roof of the White House to smoke pot and Rock & Roll President reveals that it was Carter’s son Chip and not some security guard who joined him. These were not family-friendly pop stars like the Osmonds or the Partridge Family, but countercultural figures who could very easily have hindered a candidate by tying him to drugs or sex or rebellion. Rather than undercut Carter’s gravity or mission, they helped portray him as an outsider who could clean up the mess made by Nixon and Watergate.

As the documentary makes clear, however, this wasn’t just politics as usual. There was no strategy behind Carter’s partnership with these southern musicians. Instead, it came about more organically, a happy accident stemming from his clear love for the music. He and several other talking heads say as much in the film, but the most convincing evidence is visual. Rock & Roll President is filled with archival footage of the President watching and listening to a wide array of music — not just rock, but folk, jazz, gospel, and country — and at every concert he’s there singing along and smiling his big, toothy smile. Rather than playing up a focus-group-approved reaction, he lets his guard down and projects something resembling pure joy. At 95, Carter remains an imposing and presidential presence. Yet, especially when he’s recalling a particular concert or simply putting a Dylan record on the turntable, that unselfconscious smile returns, its hint of mischief intact.

Rock & Roll President includes interviews with a range of artists, some of whom are still identified as progressives (Rosanne Cash, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan) and others who have swayed further right over the years (Larry Gatlin). But they all respond to Carter’s calls for bipartisanship, his moral leadership, his steady demeanor in office, and of course his musical knowledge. Over time many of his accomplishments have been dismissed, undone, or simply swept under the rug, but the documentary connects some of them — his handling of the historic peace treaty between Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, for example — to Carter’s Christian faith and the principles he found in music.

There are, of course, holes in the story Rock & Roll President presents, but Carter’s idealism is refreshing especially at a moment when politics has become ugly, divisive, and cynical to the point of nihilism. He comes across as a folk hero: embraced by the people and too honest for politics. “There was so much about the story that is timeless, in terms of messaging,” says director Mary Wharton. “During filming and production, there were all these things that would happen in the news that resonated with the stories that were being told in the film. Things like Carter’s role in the Civil Rights movement continue to be more and more relevant.”

She and producer Chris Farrell spent three years researching and filming the documentary, which included two trips down to Plains, Georgia, to speak to the former peanut farmer himself. For our latest Roots on Screen column, BGS spoke to the duo while they were in Massachusetts for the Berkshire International Film Festival, where Rock & Roll President played at a drive-in theater — just like it was ’76 all over again.

BGS: In the film, Carter seems to be very unselfconsciously enjoying himself around this music whenever there’s live footage. What was he like to deal with?

Chris Farrell: He’s in his mid-90s, first of all. He’s a former President. He’s a naval guy. He’s pretty stern, and even in his advanced age, he’s still pretty imposing. He shows up to the interview and sits down and he’s very serious. But within the first three to four minutes, he realizes this is not the typical interview. We want to talk about his love for music, what music meant to him, and how he used music in his personal and political life. I’ll never forget — that smile just showed up, and you can see it in the interview.

Mary Wharton: We were told that President Carter was a very punctual man and that we needed to be ready when he walked in the door. They said he’s not very patient in terms of waiting around for you to get ready for him. He’s a very exacting person who does not suffer fools. And why should he? But it was obvious that he had enjoyed talking about this stuff, and that he had a lot of fun with it. I think he genuinely enjoyed sharing this part of his life that he had never really been asked about before.

Was he the first president to use music this way? How unprecedented was it to have endorsements from this kind of countercultural creative class?

MW: JFK got the endorsement of Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack. I don’t know if they were doing campaign benefits for JFK or not — I never researched that — and the only other thing I could point to is Nixon inviting Elvis to the White House, because Elvis wanted to be made a sheriff or something along those lines. But that didn’t seem like anybody endorsing anything…

CF: And Johnny Cash, remember? Nixon tried to co-opt Johnny Cash and it didn’t work. Again, the interesting thing was: This was not marketing necessarily for them. As the film shows, from his very early childhood, music was massive in Carter’s life. It was very, very important to him, and that’s why it made a natural component to his campaign. It wasn’t like some campaign manager said, “Hey, listen, boss, just trust us on this. You know, if you hang out with these guys, you’re gonna get endorsements and people are going to like you.” He genuinely loves music, all music, and he really, really felt a strong relationship and bond with these guys, and that’s what made them willing to endorse him.

And these weren’t just any old musicians either. They were Southern musicians who seemed to be redefining how the South was being depicted. The Allmans and Skynyrd were popular right when you’re having movies like Walking Tall and Deliverance, and suddenly there are new ways of thinking about the South.

CF: Mary and I are both from the South — and not terribly far away from where Jimmy Carter is from. We’re both from North Florida. Even though we were young when he was elected — I was ten, Mary is slightly younger than me — we spent the ’70s in the South and we remember that it was changing. As Chuck Leavell says very well in the film, and Rosanne Cash says extremely well, things were going in the right direction, and Carter personified that attempt to move us along not only in the South but the country as a whole. Unfortunately, a lot of those issues we were making progress on then, it feels like we’ve gone backwards on, whether that’s civil rights, women’s rights, a whole host of issues.

Looking back, many of the artists associated with that movement are now seen to be very conservative, while Carter was and remains very progressive. It’s interesting to see footage of him sharing a stage with Charlie Daniels.

MW: Charlie Daniels [became] very conservative. But he was more affiliated with Carter and was onstage at his campaign rallies. He did a lot to support Carter at the time, then had a bit of a change of heart during the Reagan administration. Larry Gatlin is another one who’s in our film who is now very conservative. At the time, though, he did support Carter. He saw that Carter was a good man, and he believed in him. The country was a little less polarized back then. As John Wayne says in that clip in the film, he’s a staunch Republican and was known for being “the opposition.” But he makes clear he’s a member of the “loyal opposition.” He saw that Carter was president and said he would support him as best he could. We as Americans may not always agree on every issue, but we need to figure out how we can work together to come up with some kind of compromise that we can all live with. We’ve gotten to a point where that doesn’t even exist anymore.

CF: That’s ultimately the point of the movie: that Carter was able to use music to bring people together. We have so many examples of how music broke down barriers and brought people together, unified people — and would it be nice to think that, somehow, that can happen again.

MW: We had an early screening of a rough cut in New York, just some friends of mine and the editor. We just needed to get some feedback from some outsiders, and there was this one woman in the group who had a very visceral reaction to the Charlie Daniels piece of music in the film. Charlie Daniels is playing at this campaign rally in 1980 where the Ku Klux Klan showed up and were counter-protesting and demonstrating outside the rally. Carter stood up to them and essentially called them cowards for hiding behind white sheets. Charlie Daniels got up on the stage and performed, and that was why we wanted to play that music. This woman so associated the music of Charlie Daniels with many of the beliefs that the KKK espouses. She saw Southerners as automatically racist, and that’s a common misperception. I’ve heard people say, “Oh, you’re from the South, but you’re not a racist. What made you change your mind?”

CW: One of the most beautiful examples of that is the jazz on the White House lawn. There’s the sheer brilliance of those musicians and how Carter brought them all together and how he honored the genre. Carter said part of the reason that jazz had not been recognized over the years was racism. He was able to talk about racism in a way that eludes so many politicians. They find it a difficult topic to deal with, but he tackled it head on. That’s one of those scenes where you really get the essence of Jimmy Carter, where he really shows moral courage and moral leadership.

What I find remarkable is that he’s able to connect that to his Christian faith, which is another issue that people seem to have misperceptions about. Christianity is usually associated with a very specific political stance.

CF: The best example of that in our movie, I think, is the Gregg Allman story, because, to me, that’s the essence of Carter. He didn’t judge Gregg Allman, and he didn’t think he needed to forgive Gregg for something, because he knew it wasn’t his place to forgive him. It was his place to be compassionate and be there for his friend in his time of need. I consider myself Christian. I’m an Episcopalian, and to me that’s what Christianity is all about. It’s about love. It’s about compassion. And I think that he really does exhibit those attributes.

Carter seems to be thought of as a failed president who really came into his own after he left the White House. But the film argues that the traits we associate with his humanitarian efforts were the same traits that guided his presidency and the same traits he found in the music he loved.

MW: The thing we wanted to do with Carter was look at him through this different lens of his relationship with music, and perhaps that might make people reconsider their ideas about his presidency. Jim Free [formerly special assistant on congressional affairs], who’s so great in the film, got angry when he talked about how people saw Carter as a bad president. On both sides of the aisle, people will say, “He was a terrible president, but I love what he’s done post-presidency.” And that would just make Jim angry. He said, “If you like what he’s done post-presidency, then take another look at what he accomplished during his administration because he was about the same things. He wasn’t always successful, because the presidency is not a dictatorship. It’s not a monarchy. You can’t just decide what you want to happen and then, lo and behold, it happens. You have to work with Congress. What Carter was able to accomplish puts him on the right side of history.

CW: If people would go back and look at the record — and we could have done this with the movie, but we decided not to go down this path, because Stu Eizenstat wrote a 900-page book about this — they’d see that Carter had an enormous amount of legislation, some really groundbreaking legislation. He’s one of the most efficient and effective presidents in history, in that regard. Nile Rodgers rightly says that Carter got the short end of the stick somehow. Hopefully, upon further reflection and examination, people will hold him in higher stead. And he loves music and understands that it has this incredible power to bring us joy, to bring us together, and to remind us that we’re more alike than we are different. We all want to dance to a good song.

Lede photo, Jimmy Carter and Rosalynn Carter photo, Jimmy Carter on stage photo, and Jimmy Carter interview photo: courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment; Photos with Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris, and photo with Dolly Parton, from Carter Presidential Library.