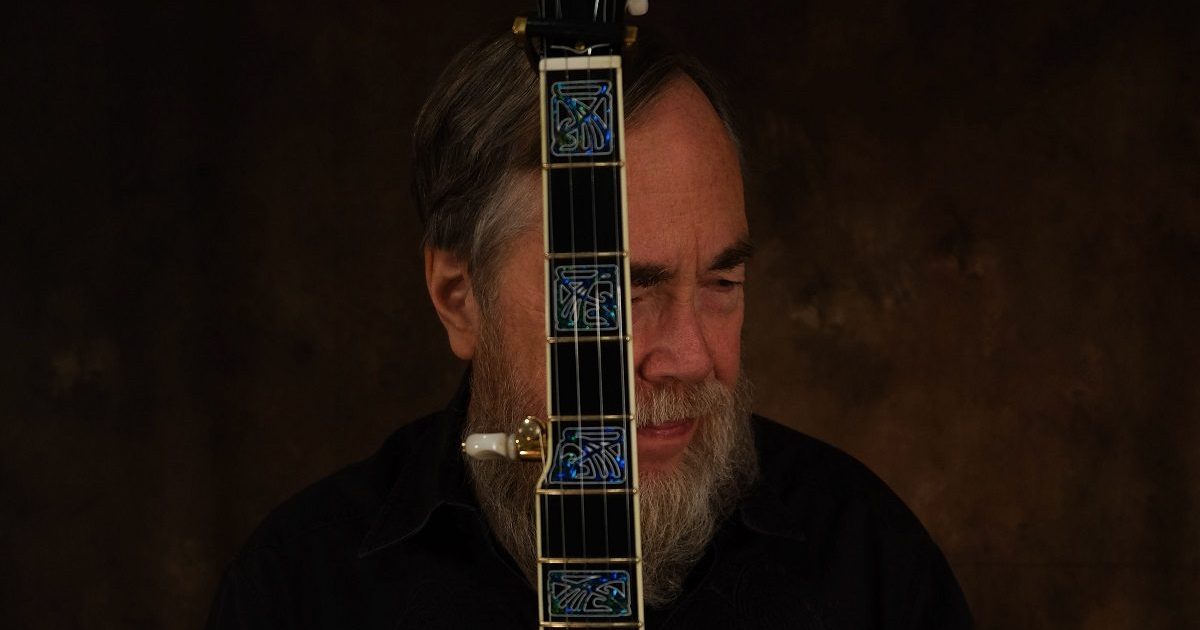

Singer/songwriter H.C. McEntire has been making music for many years now — formerly with the punk band Bellafea and more recently with the indie country outfit Mount Moriah. But last year, she paused that trajectory to tour with Angel Olsen. Speaking from her home in North Carolina, she explains, “There are not many voices I’d put my own career on hold for.” The opportunity was an exciting one, but McEntire’s not prone to multi-tasking, so she found it hard to stay connected to her own creative direction while touring someone else’s.

Enter: Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna. A chance encounter between the two women developed into a professional acquaintance, which eventually became a strong friendship. Upon request, McEntire sent Hanna her entire hard drive of demos, hoping Hanna could forge a path through the disparate songs she’d written outside of Mount Moriah’s catalogue. “A lot of it was weird, abstract punk stuff that didn’t fit in to other things I was making, and some of it was real sweet pop, kind of twee,” she says. “It was all over the place.” Rather than cull together the raucous material, Hanna saw something in McEntire’s folk-driven country tunes, so the pair worked closely to refine the ideas that’d been bubbling on the margins for years. Sometimes, in order to find your voice, you need someone to guide you back to it.

McEntire’s resulting debut solo album, LIONHEART, sets about reclaiming country music from the bros, belles, and other tropes that fail to leave room for new stories because they’re proscribed as “the norm.” Growing up a queer woman in the South, she’s familiar with such labels and how they’re used as an exclusionary tactic.

McEntire was raised in a Southern Baptist family; she learned about the communal inclusivity church can offer only to experience its steely opposite when she came out. The hymnal ballad “When You Come For Me” finds her questioning her place in the land that birthed her against woozy pedal steel and a quavering rhythm. “Mama, I dreamed that I had no hand to hold. And the land I cut my teeth on wouldn’t let me call it home,” she sings, her voice forthright.

She’s struggled with her faith, her family, and even herself over the years and, with Hanna’s guidance, has channeled the result of those trials and the subsequent peace she’s found into LIONHEART. On “Quartz in the Valley,” the conventional images that have long embodied the South shed their sheen: Mascara-caked lashes smear after a long, passionate night, bouffant hair wilts with the sunrise. McEntire repurposes the region in her image, making a space for herself rather than waiting for a space to be made. There’s no metaphor more assertive than when she sings “this gravel road don’t need paving.”

What does Americana mean to you, and how have you found yourself defining it in your own terms?

It’s situational for me. I think a lot of us end up using it, and we don’t totally know why or, at least, I don’t know where it all started.

It’s a more recent definition for a lot of different styles, like an umbrella term.

That’s how I feel, too. Not that it doesn’t have value, but I think it’s kind of … I’m sure there’s a fancy word for it, but just like a term that gets used so much you forget what it means.

And yet somehow manages to be exclusive.

Right, because people think Americana isn’t country, like there’s a hard line there. So I guess my answer is I don’t know.

You’ve played other musical styles in the past, your musical career, but the traditions you cull on LIONHEART harken back to your upbringing. Why was it important to use that music to make this statement?

I think as I’ve gotten older — and maybe it’s something that you do, you know, reflecting on your childhood and what you cut your teeth on — it just kinda happened. I started remembering what music I loved and it was a natural thing. Maybe it’s like a language that I stepped away from and lost a little bit, and I’ve been slowly trying to relearn and reconstruct in this way that fits my life.

There’s something powerful about co-opting the language that can be used against you and making it your own, so I could see musical styles serving that same idea. What did you grow up listening to?

All my family lives on one road. There’s a communal farm in the middle, and that was the hub, that was the homestead. My uncle ran a mechanic shop there, and there was always country music playing from the radio — ’80s country, pretty much — which is a lot of the country I love. Also, I was privy to all the old-time and the bluegrass that trickled in from community get-togethers, like church. Lots of hymns. That’s a big pillar for me. That’s what I remember listening to, up until I started getting some cassettes, like Bruce Springsteen and the Beach Boys. Those were supplemental, but the foundation was whatever was circulating through the radio dial or the church.

You said you’ve strengthened your connection to your faith in recent years?

It’s definitely a process that I’m still refining. I grew up in a Southern Baptist family, and the church was really close to our house; my great-great-great-whatever grandfather founded it back in the 1700s. That’s just what you did. I never really thought about it. I had moments where I connected with it on a deep level, and I had a lot of moments and years where I was sort of robotic. As a teenager and later in my teens, I realized, as I started forming my own beliefs, that a lot of those were incongruent to what I was hearing on Sunday mornings, and it was really confusing. I struggled with that for a very long time. When I went off to college, I shut the door on organized religion. I felt kind of betrayed by it. It was painful; I didn’t think I had a place in it. I was bitter and, for many years, I could not talk about religion.

I can see how you’d want to stop trying to connect.

Exactly. All the while, I really felt a void. I was hungry for those moments when I was younger, when I was sitting on the pew, and I felt this profound power in the form of a congregation. Those moments where I did feel love, and I did feel faith, I was hungry for those again, but I wanted them on my own terms. They needed to make me feel valid and whole. Over the last 10 years, I lowered my guard — a lot of this is in this record, I did that. I had to be really vulnerable.

On “Quartz in the Valley,” you’ve got one of the finest metaphors I’ve heard in some time: “This gravel road, it don’t need paving.” How did you set about clearing a space for yourself in a home that hasn’t always been accepting?

That’s a cool line.

It’s a great line!

I hadn’t thought about it that way.

I thought it was such a great declaration, and I don’t even know if you meant it like that.

I definitely think I was alluding to something. All I can say is, it’s taken a long time, and a lot of stops and starts, and a lot of being vulnerable and really being active about researching certain spiritualities that I’m interested in, or experimenting with different churches in the area. It was really hard walking through the door of the first church that I went back to, but once that happened, it’s been so liberating and I realized that it’s not a formula. Re-discovering that and reconnecting with [my spirituality], I feel more whole. I feel whole in a way that I’ve never felt. I’m allowing my spiritual journey just to be whatever it is. I don’t really adhere to labels or anything, so I just want to grow.

I feel like any time you add a descriptor to an experience like that, people tend to characterize it in terms of exclusion.

Exactly. That word “exclusion,” to me, that is really confusing when you talk about spirituality because it’s the opposite of exclusion. But there’s so much of that, especially in the South. Certain groups find power and they quell their own anxieties and fears by excluding other people.

It’s the opposite of the message.

Exactly.

Your relationship with the land comes across powerfully in “When You Come for Me.” Where does it stand now?

When I wrote that, I was imagining the land I grew up on — the road I’m talking about with my family — and I think it also was inspired a little bit by … several years ago, I learned that my parents had bought my brother and me this plot in the church cemetery. That is actually a normal thing to do, just buy up a whole thing so your family can be together, but it made me think what that actually meant. I’ve carried a lot of pain with me over the years. I grew up in a very tight-knit family, and I love the land I grew up on. It’s in the foothills of the mountains in western North Carolina; it’s a small town. I’ve been in a lot of pain with how to relate to that particular area, socially, culturally.

Right. If they’re not making a space for you, then how do you see yourself as part of the community?

I think it’s actually more of a question to my family. It’s something I’ve been grappling with. My self-identity and yearning for that land and that inclusion, but I’ve never totally been accepted by my family. I’m still coming out to them over and over again.

Do you feel like you’ve reached a shift from proving yourself to making a statement?

There’s some peace in it. I feel I’ve reached this point where I don’t want to say I’ve stopped trying, but I’ve stopped forcing it. A lot of LIONHEART has been me reckoning with all this we’re talking about, so there must be some sort of peace that I’m at least able to write about it in a poetic way. That’s a challenge I liked: How can I connect with these communities and with different layers of myself and do it in a poetic narrative instead of a punk song or a hit-you-over-the-head anthem? I’m interested in finding that medium place where I can relate to all sides.

Kathleen Hanna isn’t exactly an artist I would place under the umbrella of Americana, but I love that you two connected and she kept wanting to talk about your music. Can you delve into that collaboration?

I’m sometimes still surprised.

It feels like kismet!

Yeah, it was a real gift that the universe gave me. I’ve looked up to her for a long time. We peripherally had been friends, but just through the music scene — the punk scene. She provided this mentorship that — I’m going to get emotional — it came to me at a time when I needed some direction. I was pretty lost creatively: I wasn’t sure where Mount Moriah was going, I’d just taken this job singing in Angel Olsen’s band that I knew was going to physically and creatively take me away from certain things.

This record would not be … it just tears me up. She didn’t have to do all that. She didn’t have to be this editor and mentor and fan of what I was doing, but it just shows what kind of person she is. She asked me to send her demos. None of us knew exactly what her role was going to be, whether it would be her producing or me and her co-writing things, and it kind of became all of the above. I sent her everything I had on my hard drive, like six or seven years. I anticipated her to be drawn to the more rocking, cathartic music that I knew she had made, but everything she picked were all the country songs. I think that’s when I knew that it was real. I needed to trust her and step back a little bit and let somebody have the first shovel dig.

Especially if you’re going through creative doubts, to have someone step in and build you up is worth more than gold.

Oh, totally. It’s been one of the most powerful things in my life. I needed someone to believe in me. I’d lost sight of that. I loved singing with Angel; I loved my role in that band, but it psyched me out too because I’m not very good at multi-tasking. There are not many voices I’d put my own career on hold for, but in the middle of all that, I got lost and Kathleen … like you said, it’s one of those things that even further connects me to the spiritual world, quite frankly.

It almost, in its own way, feels like amends for what you’ve been through.

Damn, dog. Yeah! That is a really amazing way to think about that.

Just having her listen through your entire hard drive of music … that alone … not many people would spend that kind of time.

It was symbiotic in a lot of ways. I think she got a lot out of switching gears and trying on a different hat. We were both new at all angles of it.

Are you ready to loose it on the world?

I’m ready to see what this year has in store. I’m trying not to have expectations, because this record could get panned a lot of different ways, and I could get pigeonholed a lot of different ways. It really got me out of a dark place, so I’m grateful to it, no matter what happens.

Photo credit: Heather Evans Smith