Red Mountain in Birmingham, Alabama, is one of the largest metaphors for race and class in the American South. Part of a range that cuts a diagonal southwest-northeast line through the state, it provided the ore that fed the region’s iron mills in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and more crucially it divided the city into two neat halves: downtown and over the mountain. The former has historically been the province of the poor and in particular the black, while the wealthy and the white lived over the mountain. It became a convenient barrier between the races and the classes, blocking the fumes billowing from the furnaces and largely removing the well-heeled residents of the suburbs from the ugly realities of the city.

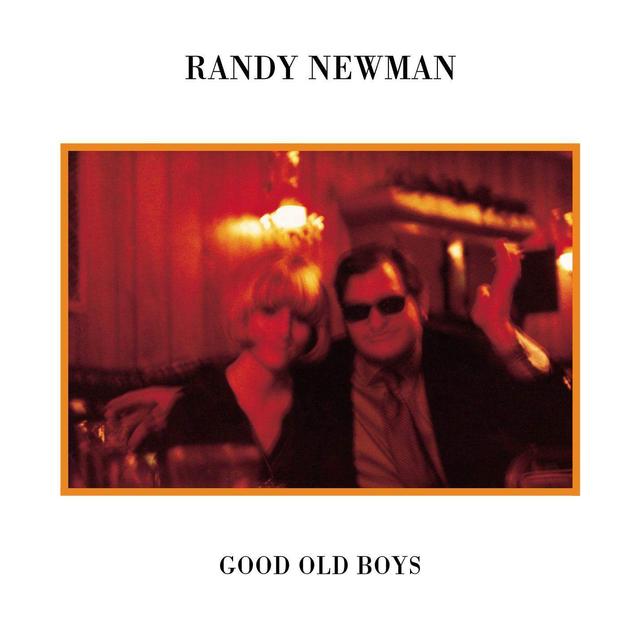

At the top of this mountain is Vulcan Park, home of the state’s most famous landmark – a 50-ton, 56-foot statue of the Roman god of the forge, cast in local iron. This is the setting for “Rednecks,” the opening track on Randy Newman’s 1974 album Good Old Boys, a squirrelly collection about race and masculinity in the South that 40 years later still has the power to provoke. The song opens with a 29-year-old millworker named Johnny Cutler sitting on a bench in the shadow of Vulcan and thinking about the governor of Georgia:

Last night I saw Lester Maddox on a TV show

With some smart-ass New York Jew

And the Jew laughed at Lester Maddox

And the audience laughed at Lester Maddox too.

In this short introduction Cutler is referring to an episode of The Dick Cavett Show, which did not have a “New York Jew” as its host but did book a range of guests including politicians, writers, musicians, and sports figures. In December 1970, his guests included actor Jim Brown, author Truman Capote, and Lester Maddox, who had campaigned on a flagrantly segregationist platform. Cavett barely disguised his contempt for the Southern politician and even dismissed Maddox’s constituents as “bigots.” After an argument in which Cavett failed to apologize to his guest’s satisfaction, Maddox walked off the set and refused to return. Because the show was filmed the day before it actually aired, newspapers reported the incident and viewership skyrocketed.

Once the song settles into its breezy ragtime swing, Cutler doesn’t defend Maddox as much as he embraces every insult ever hurled at Southerners. He proclaims himself an ig’nant redneck, a degenerate drunkard, an uneducated rabble-rouser. “We’re too dumb to make it in no Northern town,” he laughs, then gets to the heart of the matter: People like him are oppressing the country’s African American population. Except he doesn’t say “oppress.” He says they’re keeping them down. And of course he doesn’t use “African Americans.”

The word he uses is so blunt and ugly coming from both the narrator and the writer, such a jolt in the song—almost like a punchline, as if the whole point is that Cutler and his brethren are so dub they think other races are below them—that we should take a step back for a minute. Newman of course is singing in character, but still his use of that word teeters on the knife blade of irony: The singer gets some good distance on it, but the narrator wants no distance at all.

By 1974 Newman was well-known for this kind of risky satire, having already raised eyebrows with “Sail Away,” about a slave trader advertising the glories of America. There is purpose to such provocations, and by the time “Rednecks” reaches the bridge, Newman his narrator are holding a mirror up to America. Embracing the worst aspects of the Southern character allows Cutler to turn those accusations back on his accusers. Speaking of African Americans, he sings:

He’s free to be put in a cage in Harlem, New York City

He’s free to be put in a cage in the south side of Chicago and the west side

He’s free to be put in a cage in East St. Louis

And they put him in a cage in Hough in Cleveland

And they put him in a cage in Fillmore in San Francisco

And they put him in a cage in Roxbury in Boston

Listeners may not recognize those neighborhoods—and Newman admits his character wouldn’t have known them either—but in the 1960s and 1970s, they housed segregated ghettos, neighborhoods ravaged by poverty and violence. In 1964, just two weeks after the Civil Rights Act became law, a black teenager was shot by a white cop in Harlem, resulting in six days of riots in Manhattan and Brooklyn. In July 1966, a riot broke out in the Hough neighborhood of Cleveland when a white bar owner began turning away black patrons and patrolling the sidewalk with a shotgun. In September of that same year, San Francisco police shot and killed a black youth suspected of stealing a car, sparking a neighborhood demonstration that soon erupted into a riot. Chicago alone had multiple race riots throughout the 1960s.

The point is clear: Birmingham was no more or less racially segregated than any other American city, but was being scapegoated for the sins of the entire country. It’s a tricky point to make, and Newman reinforces it with the music. Rather than setting the song in a regionally specific style, such as country, blues, hillbilly, or Southern rock, he writes in a more broadly American mode, rooting “Rednecks” in popular jazz, ragtime, and Tin Pan Alley.

No doubt Cutler would have been familiar with these sounds, even if he didn’t claim them as his own. And certainly it reveals the album’s foundation in musical theater and possibly in minstrel shows of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These flourishes of horns and strings underscore the song’s pointed view on race, refusing to distinguish the South as a place separate from the rest of the nation. Despite its history of thwarted secession, the American South remains American. Its racism, therefore, is America’s racism.

This is the main point of Good Old Boys, and the idea from which nearly every song stems. Newman conceived the album as something like a musical, which he explains in the infamous bootleg Johnny Cutler’s Birthday, a rough outline of the narrative with Newman singing, playing piano, and introducing the songs. (The bootleg was officially released as a bonus disc on the 2002 reissue of Good Old Boys.)

Roughly the first half of the record follows Cutler as he descends Red Mountain. “Birmingham” not only touts his hometown as “the greatest city in Alabam’” but provides Johnny’s working-class backstory, revealing just how thoroughly Newman had sketched out his narrator. Much less satirical, “Marie” and “Guilty” locate the character’s bruised heart through his marriage to a woman, both as gentle in their melody and as tough in their self-loathing as anything Newman has written. “I’m drunk right now, baby, but I’ve got to be,” he sings, “or I could never tell you what you mean to me.”

As the album proceeds, Cutler becomes less and less the main character, but rather one in a full choir of Southern eccentrics and roustabouts, who may not have the most sympathetic politics but earn Newman’s grudging respect for their determined self-definition. “Kingfish” is a barbed stump speech about former Louisiana governor Huey Long, the subject likewise of Robert Penn Warren’s novel All the King’s Men and a figure who recalls a certain you-know-who in his deployment of base racism as a campaign platform. Newman may be too jaded to be horrified by Long’s aggressively divisive politics, but he’s amused that the governor, eventually assassinated in the state capitol, had the chutzpah to keep his promises to the rural voters who elected him: “Who took on the Standard Oil men and whooped their ass?” he asks as the strings trill triumphantly. “Just like he said he’d do.”

“Back on My Feet Again” is a tale of woe presented as a weirdly elaborate complaint to a doctor (“Get me back on my feet again”), and “A Wedding in Cherokee County” is a monologue from a man in love with what he describes as a wild woman: “If she knew how, she’d be unfaithful to me,” he laments… or maybe boasts. “I think she’d kill me if she could.” Newman allows the man his dignity, even as he sullies himself for love, at least until the song’s end, a bridge to nowhere that serves as the album’s culmination despite the fact that there are two songs left to go: Dreaming of his wedding to this woman and then of their wedding night, he confesses, “She will laugh at my mighty sword. Why must everybody laugh at my mighty sword?”

During a decade when pop culture was presenting new exemplars of tough, moralistic Southern masculinity—think Burt Reynolds in Deliverance, Joe Don Baker in Walking Tall, or even Ronnie Van Zant fronting Lynyrd Skynyrd—Newman’s depiction of these sons of the South was subversive in its satire. These characters invite our scorn and laughter, but Newman also provokes something sympathy for them as well. He presents them as relentlessly human, if not always humane, their shortcomings reflecting the worst failings of America in general and the South in particular.