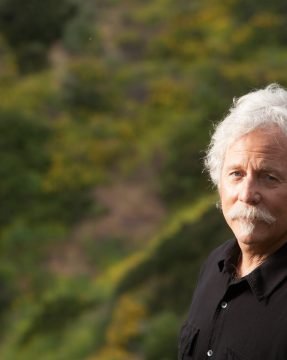

Tony Joe White’s protracted Southern drawl crackles across the telephone line. Underneath his deep, husky tone, the phone hums with a slight buzz thanks to a series of thunderstorms rolling through Franklin, Tennessee, where the iconic swamp rock musician lives. It seems fitting, as if his voice — one of his music’s trademarks — creates an electrifying response even for his landline. Conversing with White is not the same as listening to him sing. For one, he speaks softly, carefully. His speech contains no excess fat, none of the verbose over-sharing that has come to exemplify interpersonal communication in the 21st century. Instead, White is a man quietly in tune with the nature around him and the way it has helped him write some of his most definitive songs.

Classics like “Polk Salad Annie” and “Rainy Night in Georgia” aligned White’s name with a musical style evoking heat, humidity, and good ol’ Southern funk. They also garnered the attention of Elvis Presley, Dusty Springfield, and others who have covered his work over the years. But don’t relegate White to the past. Yes, he’s a legend; but that doesn’t mean his best work is behind him. His newest LP, Rain Crow, shows he hasn’t slowed down and has no intention of doing so.

The album’s opening number ,“Hoochie Woman,” focuses on the relationship between a conjure queen and her “Smoochie Man.” But as wild and feverish as that song sounds, it’s not White’s only writing talent. He’s equally adept at love songs. They appear throughout his repertoire, vulnerable and honest offerings about the power that emotion has over him. One such track on the album, “Right Back in the Fire,” looks at a relationship still burning with passion even after many, many years together. It brims with a heat equally indicative of the song’s title, as well as White’s feeling for its subject.

At 72, he’s still channeling the inspiration — the itches — he gets for new music. They are the ideas that bubble in his psyche until he knows he has to sit down and work something out.

I read that you like to build fires in order to write music, and there’s certainly a heat about your work. At first, it could be attributed to the Southern region that bred this sound, but perhaps there’s a greater sense of what you’re using to help you compose. What does fire bring to the songwriting process?

I can’t say, but the fact is, I’m part Cherokee Indian. My mom was half, and I always really liked to be around fire. Over the years, I would say 90 percent of the songs I write I’ll be around the campfire with a cold six-pack of beer. I go out on the river and build a fire and sit there with it, and suddenly a guitar lick comes up, or a line, so it helps me. Whether it’s real or not, in my mind, it does.

It ties you back to some essential part of the past.

It could be, yeah. I never really give a whole lot of thought to the end of it, but like I said, when I get some kind of idea in my head — a guitar lick or a line — usually that evening I head down to my spot and I’ll build a fire and it will come. I really like it in the Fall and even when Winter comes. I got a spot out there by the shed that kind of leans out and I keep the fireplace under it and, if it rains or snows or sleets, whatever, it don’t matter. It sounds good on that tin roof, and I got all the warmth I need right there. It’s important.

It seems like many musicians nowadays take to the studio once they have an idea, but they lose that connection with nature, with a distinct environment.

Yeah, there’s plenty of times, if I’ve got a machine — a tape machine or something — I lay something down and play it back. I don’t notice it at the time, but I’ll play it back and I can hear a screech owl, sometimes even a lone wolf down the river. I’ll send ‘em over to the publisher or the record company and they’re like, “Man, who’s your background singer?” I go, “The very best.”

You say sometimes you get a lick or a line. Where do you believe that comes from?

It all comes from up above. Everything. It’s all God-given. You just have tov…vwhen it comes by, you grab a piece. You do your best to make it turn out as it can turn.

How are you able to refine what you’re given?

I don’t know.

That’s fair. It’s a hard thing to articulate where creativity comes from.

Yep.

Characters play a large role in your songs. What interests you about that kind of songwriting or subject matter?

You know, my songs go all the way from stuff like “Rainy Night in Georgia” to love songs to alligators to the street. It goes everywhere. I never really try to direct it or know which way it’s going to go. I think to have total freedom in that way. If I don’t try to corral them, I never know how they’re going to turn out.

“Rainy Night in Georgia,” I drove a truck on the highway in Georgia. I’d just got out of school and was staying with my sister, so I was trying to write about things I knew, but also things that were real. So "Polk Salad Annie" was a real girl down in Louisiana, or maybe three or four girls could be "Polk Salad Annies." Then there was "Willie and Laura Mae Jones," a Black couple that was not too far from us and we picked cotton together and we played guitar together, he did and I did. So the characters went right along with staying real with this stuff. Then, all of a sudden, a love song will pop up or a song like “Mother Earth,” for instance, trying to say that there’s something to helping the environment. I never know which way they’re going to go.

Who has helped inspire you throughout the years?

Oh man, that’d be hard, because I have so many heroes I care about. I’d have to go all the way back to the very first — Lightnin’ Hopkins doing “Baby, Please Don’t Go.” That kinda kicked me into the guitar. I was about 15.

As far as artists doing your songs, a lot of them are my heroes: Tina Turner, Joe Cocker, Elvis even. Not only were they doing the songs, but I was actually getting to go in the studio and play guitar with them. I feel like I was a real part of that vibe they were putting out at the time. “Steamy Windows,” for instance, from Tina … it was like a live show inside the studio.

God, that must’ve been something.

It was.

As you’ve gotten older and you’ve become someone other songwriters and artists look at as a hero, how has that affected your outlook?

I hadn’t really given it that much thought. I just come off a tour two days ago and so many people come up to me and say stuff like that and it’s fine and it’s good, but I mainly — like I told you at the very start of the conversation — just try to stick close to an idea. I got this one tune that’s really been bugging me lately. It’s fixing to be popping out soon. But if somebody really means it, say, “God, you really kicked me with this.” That would make me feel good.

But it’s not the defining mark.

No.

What kind of advice would you give to younger songwriters?

I would say only write or play what’s in your heart, straight in your heart. And not try to do it for radio, TV, or YouTube and others. Write what you think is important to you.

I think that’s applicable to so much more than songwriting

It pretty well covers it.

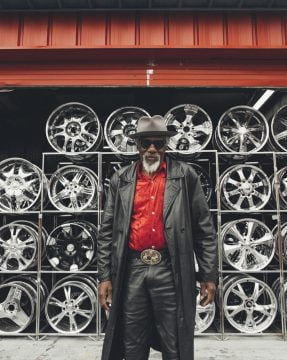

Photo credit: Joshua Black Wilkins